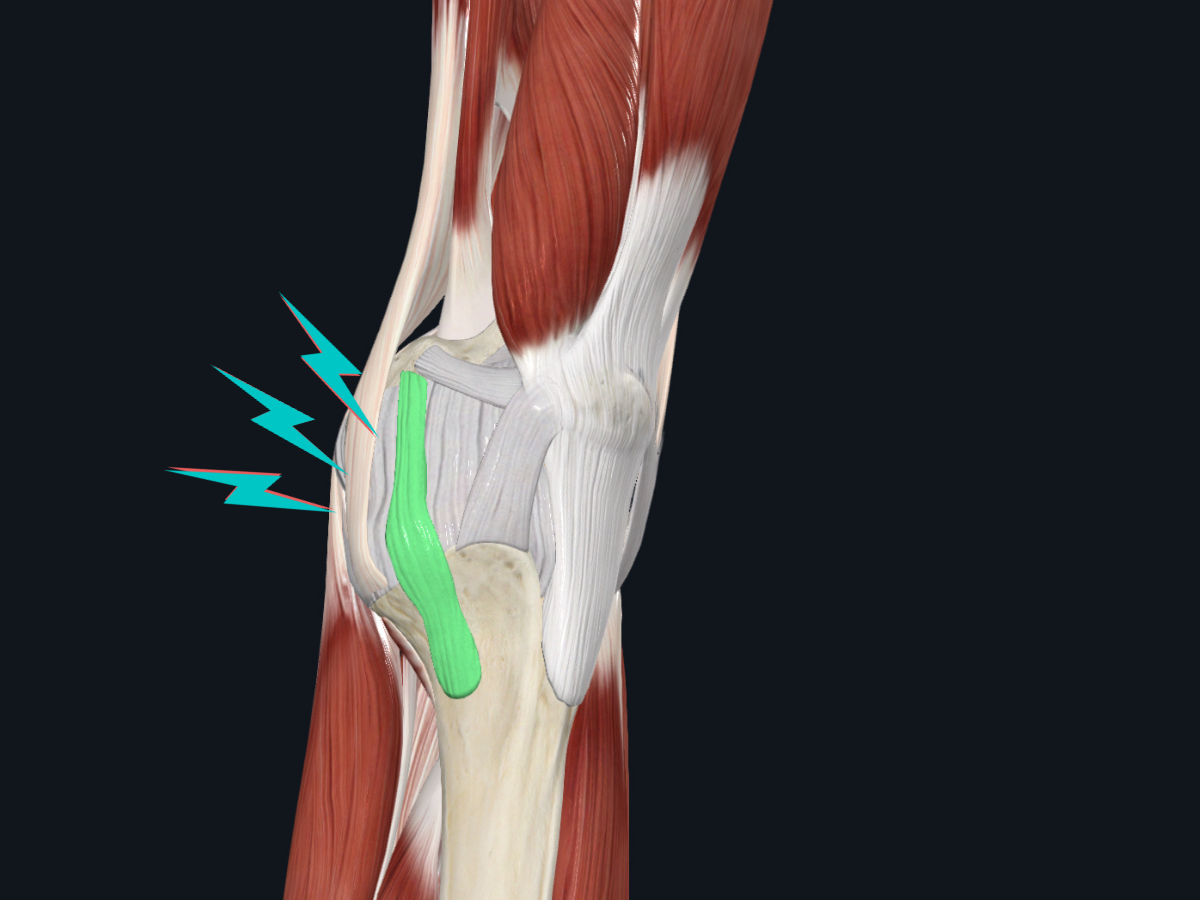

What is an MCL tear?

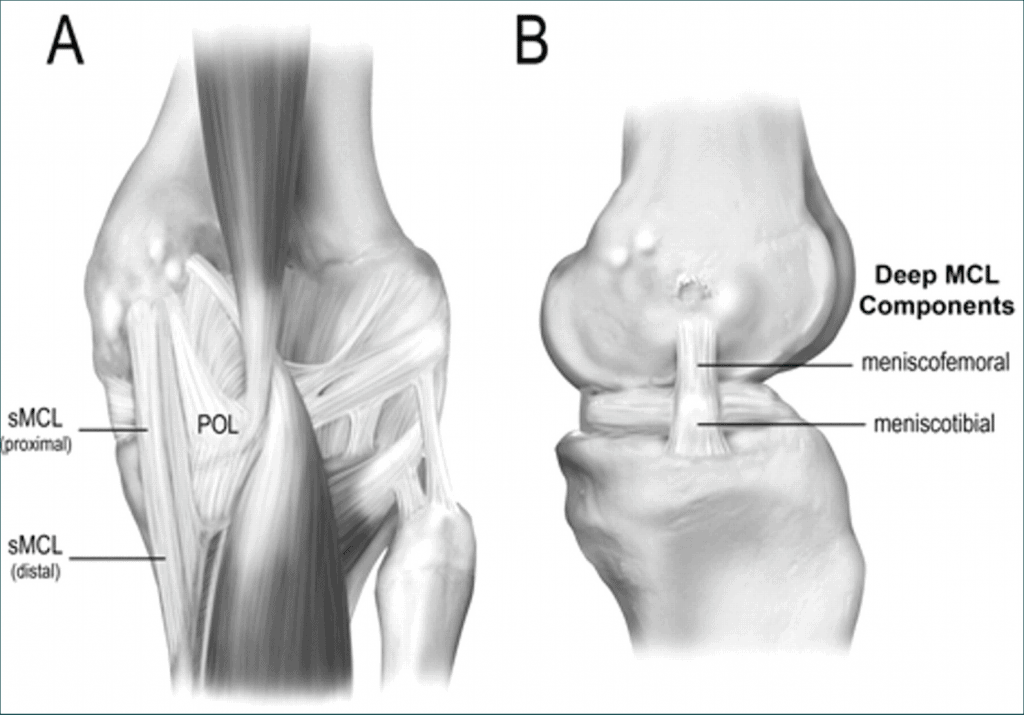

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is the most commonly injured ligament in the knee.1 The MCL consists of an outer layer (called the superficial portion) and an inner layer (called the deep portion). The superficial fibers of the MCL are orientated vertically and mainly control medial forces (known as valgus stress) to the knee. The deep fibers of the ligament primarily resist internal rotation forces of the knee. The deep fibers also have connections with the medial meniscus. Between the superficial and deep portions of this ligament lies the MCL bursa.

The inner knee also gets dynamic stability from the muscles surrounding that area, including the gracilis, semitendinosus and sartorius muscles.

An MCL sprain occurs when the forces applied to the knee exceed the load capacity of the ligament, leading to damage and potentially instability.

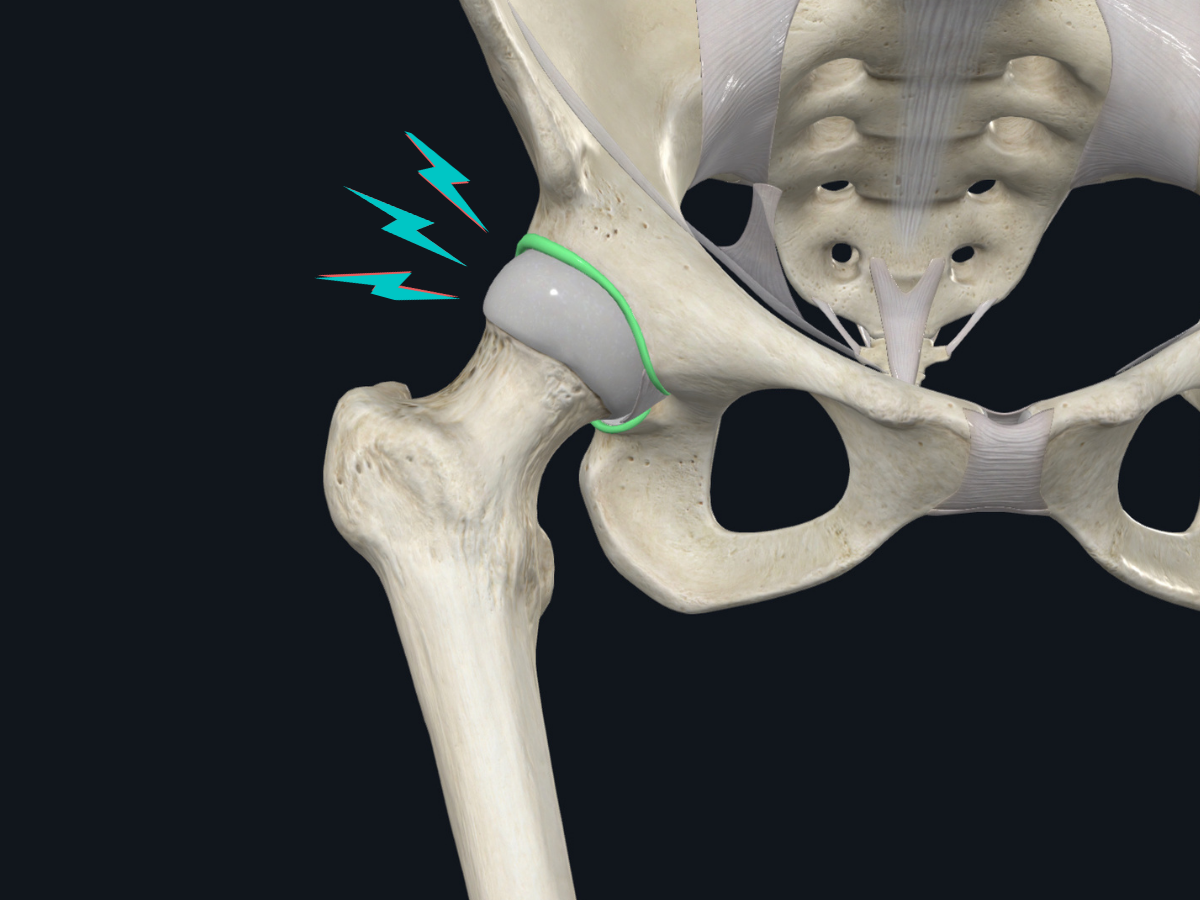

How does the MCL become injured?

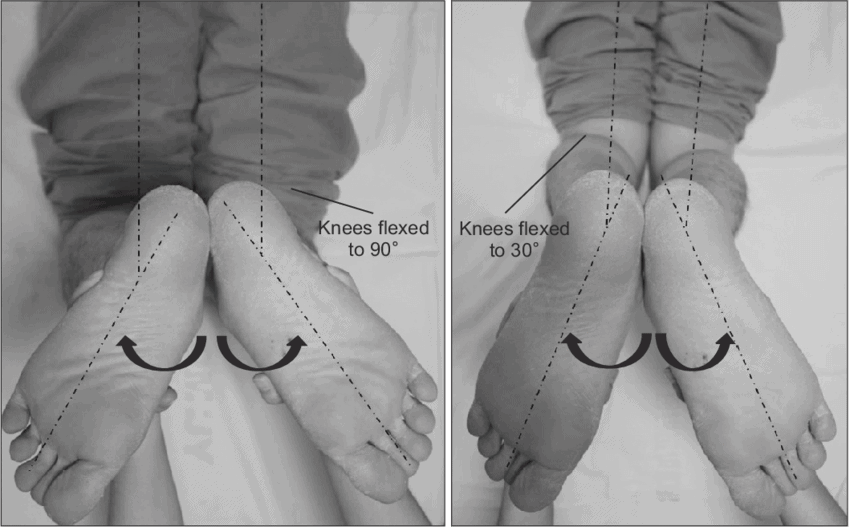

A large force to the outer aspect of the knee, especially with the foot planted on the ground and combined with external rotation of the lower leg, creates an inwards force on the knee (called valgus). Typically this occurs with the knee in a slightly bent position (~30 degrees of knee flexion).

How is an MCL tear diagnosed?

An MCL tear is diagnosed primarily based on clinical signs such as joint laxity, localized pain and swelling at the medial knee, a plausible traumatic injury mechanism, and positive clinical tests. These tests include the valgus stress test and the dial test.

How are MCL tears classified and what are the healing times?

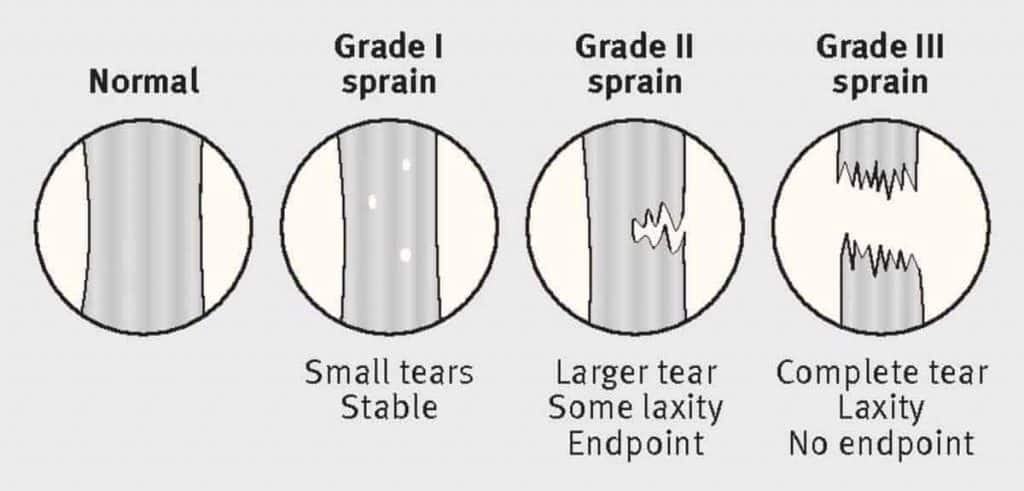

Grade 1

Injury has occurred but no instability is present. These typically recover within 7-10 days.

Grade 2

Injury includes partial fiber disruption (typically of the superficial fibers), mild instability and localized pain may be present. With accelerated rehab, these can take a minimum of 6-8 weeks.

Grade 3

Complete disruption of the MCL, which may include multiple layers (superficial and deep). In the majority of cases, other structures such as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or meniscus may be injured alongside a grade 3 MCL sprain.2

Fortunately, the medial collateral ligament tends to heal well due to an adequate blood supply to the region.1

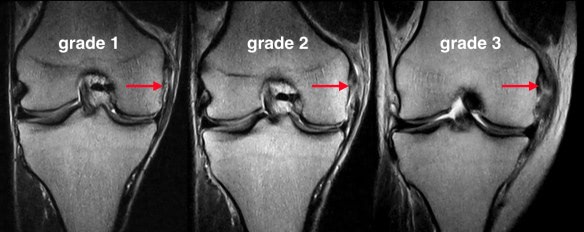

Do I need an MRI or other imaging?

In most cases, the clinical exam findings are sufficient to guide an effective therapy program. If your therapist finds excessive laxity or pain, or suspects involvement of other knee structures, an MRI may be useful. This can help guide treatment decisions and can alter recovery timelines. An x-ray can be useful in chronic medial knee pain, which can help rule out conditions such as Pellegrini-Srieda Syndrome or multi-ligamentous injury.

What is the best rehab approach to an MCL tear?

In general, early protection is important followed by an accelerated rehab program depending on the individual. This may include the use of crutches and a rigid knee brace that limits the end ranges of your knee extension, flexion, rotation, and valgus. In our experience, rehab can usually progress quicker when only the deep fibers of the MCL are involved.

What can I expect during rehab after an MCL injury?

Depending on the severity of the sprain, the management of an MCL sprain follows four phases:

Phase 1: Protection phase

- For the first few weeks, crutches and a knee brace may be necessary to allow the MCL to fully heal. The knee brace should have rigid supports and the ability to limit movement of the knee. Range of motion is gradually restored as the MCL heals.

Phase 2: Strengthening and Return to Running

- At around the 4 week, strengthening exercise difficulty is gradually increased and a return to running program is initiated.

Phase 3: Return to training

- In this phase, more sport-specific functional drills are introduced to allow you to become more comfortable with the demands of your activity.

Phase 4: Return to play

- After passing a series of functional tests, you can safely return to sports.

What are the goals of rehab?

The main goal is to safely return you to your sport or activities. From your therapist’s perspective, we are concerned with:

- Maintaining overall fitness and comfort with the demands of your sport

- Restoring symmetry (strength, motion, etc) between your left and right leg

- Minimizing joint laxity

- Avoiding surgery

- Avoiding the development of persistent pain

- Protecting the long-term health of your joint

Conclusion

While the MCL heals well, it is important to seek proper care immediately following a suspected medial knee injury to prevent long-term issues such as instability. A well-designed rehabilitation program can help the majority of people successfully recover from an MCL sprain.

References

- Andrews K, Lu A, Mckean L, Ebrahim N (2017) Review: medial collateral ligament injuries. J Orthop 14:550–554

- https://bit.ly/2BDIZIK

.png)