What is a meniscus tear?

Meniscus tears represent the most common intra-articular knee injury and are the most frequent cause of surgical procedures performed by orthopedic surgeons.2 In younger populations sports-related injuries are the most common cause of meniscal injuries accounting for over 30% of all cases.3 A forceful twist or sudden stop can cause the femur to grind into the top of the tibia, pinching and potentially tearing the cartilage of the meniscus. The mechanism of injury typically involves cutting or twisting movements or actions involving high force while weight-bearing on a bent knee.

Damage to the meniscus often occurs concurrently with other ligament injuries, particularly when the medial meniscus is involved. Sports-related meniscal injuries are accompanied by anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in over 80% of cases.4 This is partly due to the medial meniscus having attachments to other structures in the knee and partly due to high impact forces often being directed towards the outside of the knee. Lateral forces being applied to the knee causes the lower leg to externally rotate relative to the femur and places the knee in a position where the medial meniscus is particularly vulnerable. As such, injuries to the medial meniscus occur at a five-fold higher rate compared to the lateral meniscus.

Damage to the meniscus can also occur in a degenerative manner. Degenerative tears may occur with minor movements and patients typically experience repetitive swelling but can’t recall a specific injury. The risk of developing a torn meniscus increases with age as cartilage experiences age-related changes in blood supply and resilience. Increasing body weight also increases the risk of degenerative tears. It is estimated that 60% of patients above the age of 65 years old have a degenerative meniscus tear, however more than 50% of meniscal tears are asymptomatic.5

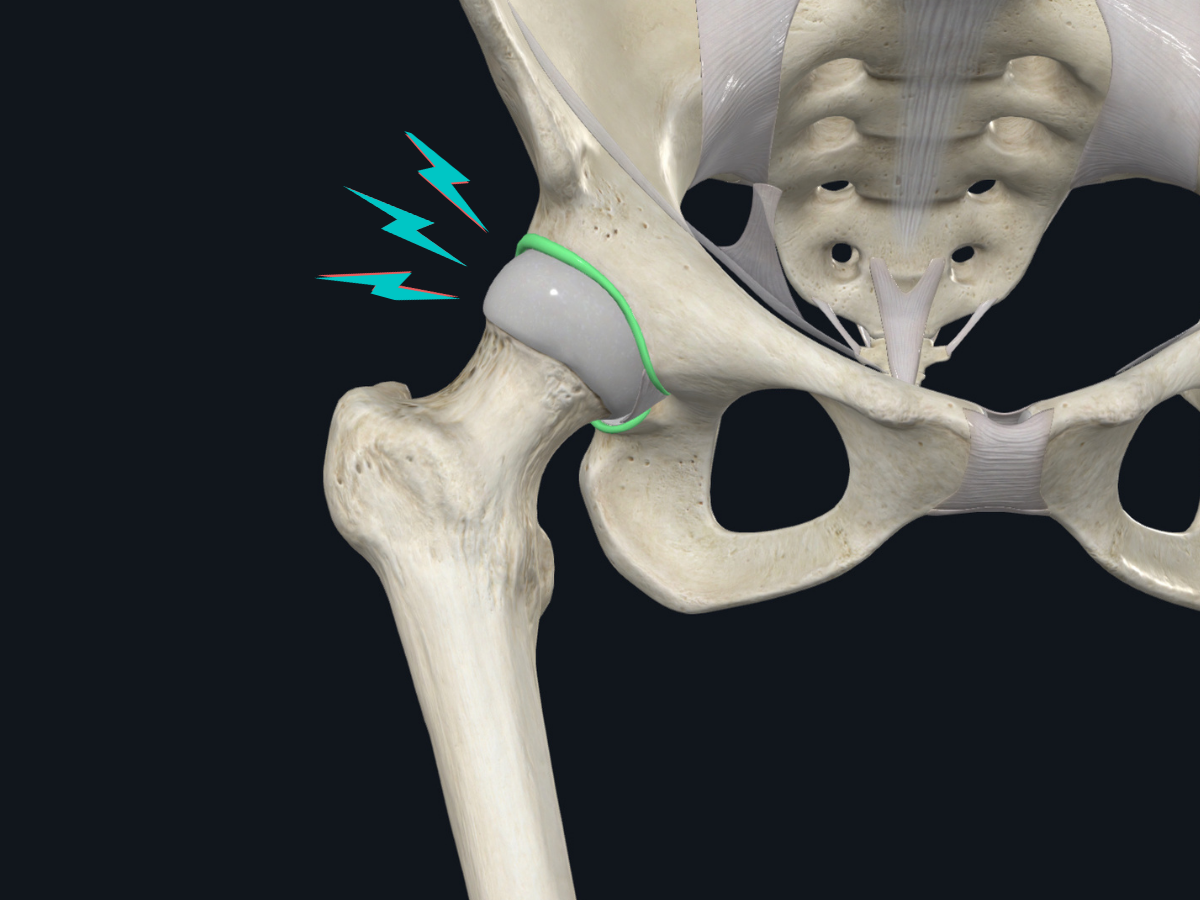

What is the function of the meniscus?

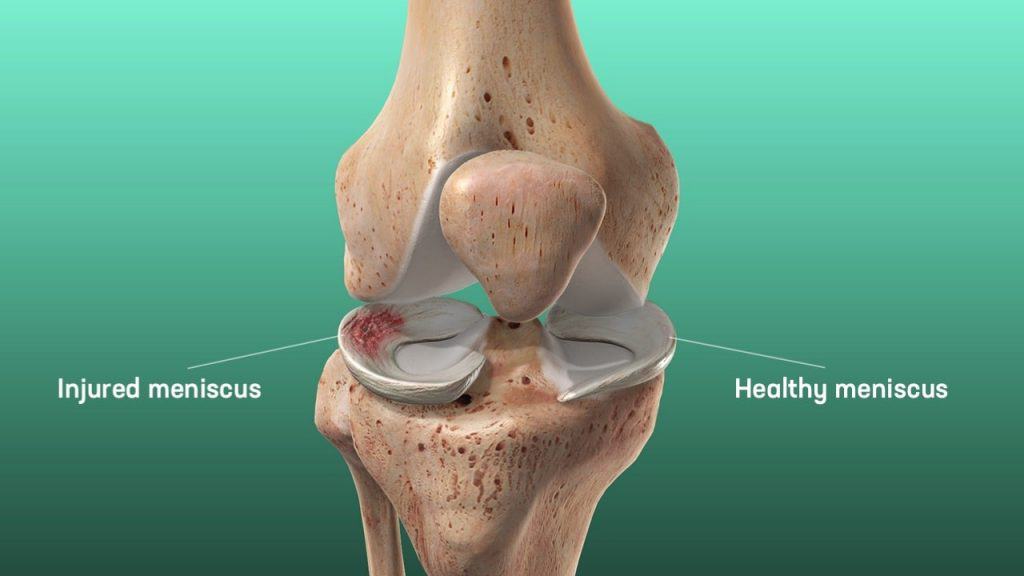

Each of your knees has two C-shaped menisci, one on the inner side – the medial meniscus and one on the outer side – the lateral meniscus. The menisci are fibrous cartilage that acts to distribute stress across the knee joint during weight bearing. In their absence, uneven weight distribution could cause the development of abnormal and excessive forces and early damage of the knee joint. The menisci also contribute to joint stability, shock absorption, joint gliding, prevention of hyperextension, protection of joint margins, and nutrition and lubrication of the articular cartilage.1

What are the symptoms of a torn meniscus?

After a meniscus tear the knee joint will typically be painful and swollen with some movement restrictions. As the irritation gradually begins to settle after the initial inflammatory response resolves, symptoms that typically develop include:

- Pain with long distance running or walking.

- Swelling and a feeling of tightness in the knee joint.

- A popping sensation, particularly when using stairs.

- A sensation of knee instability.

- Catching/locking where the knee cannot be fully straightened. This occurs when a piece of the torn meniscus folds on itself and blocks full range of motion typically between 15 and 30 degrees of flexion.

What are the types of meniscal injuries?

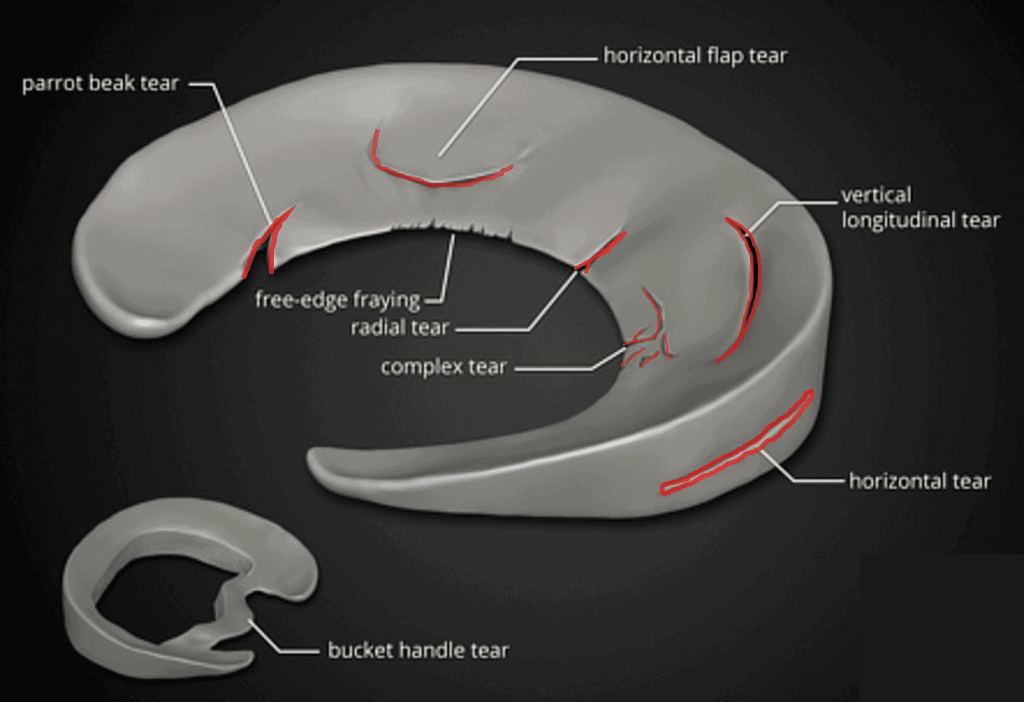

A physical examination may be able to predict whether there is damage to the medial or the lateral meniscus, however diagnostic procedures like MRI or arthroscopy are needed to classify the specific location and appearance of the tear. Tears in the meniscus are usually described based on their anatomical location and by their appearance. Most meniscal tears are classified as either vertical, longitudinal (bucket-handle), transverse, or degenerative.

Can a mensicus tear heal?

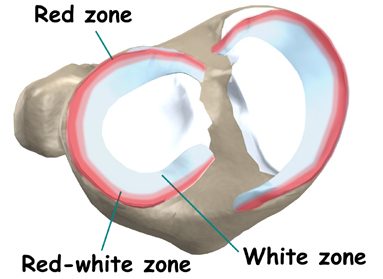

Knowing the location of the tear is an important factor in deciding the best course of management. The meniscus has variable blood supply to different regions, with more blood supply being associated with higher potential for recovery. The meniscus is broken down into three different zones based on its vascularity.

- Red zone: the outer perimeter of the meniscus which receives adequate blood supply.

- Red-White zone: the mid-zone of the meniscus where blood supply is decreased.

- White zone: the innermost portion of the meniscus which has almost zero vascularity.

Lastly, meniscal tears are classified based on their thickness. A tear is considered complete if it goes the entire way through the meniscus, if the tear is still attached to the body of the meniscus it is considered incomplete. Complete tears are additionally subdivided into stable and unstable tears, a stable tear does not move and has an increased probability of healing on its own, unstable tears allow the meniscus to move abnormally and are more likely to require surgical correction.

What is the best treatment for a meniscus tear?

Factors that are considered in determining treatment for a meniscus tear include:

- The patient’s age

- The patient’s activity level

- The location and type of tear

- Injury symptoms

- Any other associated injuries (such as the ACL)

The primary options after a meniscus injury are non-operative rehab, surgery to trim out the area of the torn meniscus, and meniscal repair. There are other procedures such as trephination/abrasion to promote healing in the meniscus and meniscal replacement however these are less commonly used and still require further long-term follow up studies.

Do you need surgery to repair a torn meniscus?

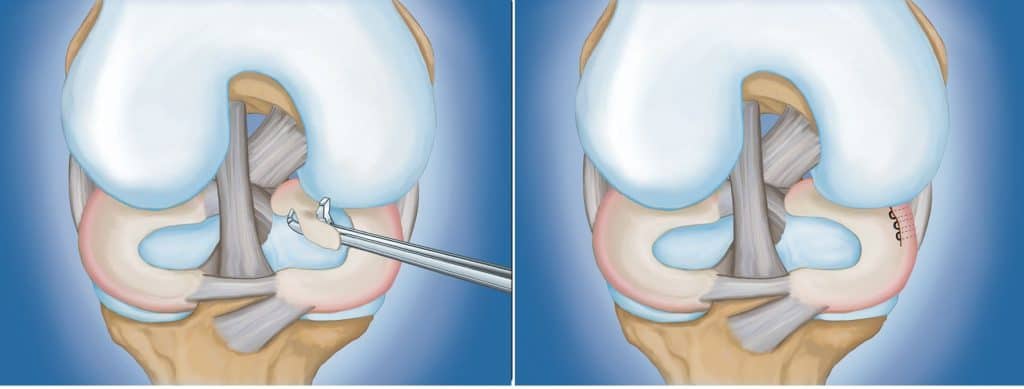

Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) is used for tears in the inner 2/3 of the meniscus where there is little-to-no blood supply. The goal is to stabilize the meniscus by removing the torn portion and as little of the meniscus as possible. Complete meniscectomy involves the complete removal of the damaged meniscus. This is only done when deemed absolutely necessary as it associated with development of degenerative changes in the knee joint.8

Meniscal repair is performed on tears near the outer 1/3 of the meniscus where there is good blood supply, or on large tears that would otherwise require total removal. The torn portion is repaired using sutures or an absorbable fixation device that joins the torn edges of the meniscus allowing them to heal.

There is an increasing amount of literature that supports meniscus repair techniques for treating tears in the red zone. Functionally successful outcomes in young individuals with stable knees are fairly frequent with success rates varying from 63-91%8, however the successful application of repair in older populations is less promising.9

Most guidelines and expert opinions refrain from recommending surgery as the first-line treatment and instead prefer to first try non-operative management, especially in degenerative tears. Patients who utilize exercise and physiotherapy as a first-line treatment tend to have similar to better outcomes in terms of strength and perceived knee function compared to those who undergo APM.12

Many smaller tears in the meniscus will heal without surgical treatment. Partial tears, degenerative tears, and stable tears are typically observed within 2-3 months of supervised rehab, and if symptoms improve or disappear within 3 months then surgery is unnecessary. More recently, studies have compared APM to placebo surgery and have found no evidence to support the benefit of APM over non-operative management. Current guidelines advocate for surgery only after a failed attempt of non-operative treatment.13

What is the recovery for an injured meniscus?

Rehab and physiotherapy are necessary after a meniscal injury to restore range of motion, strength, movement control, and normal activity. There may be a period where range of motion is restricted, especially while weight bearing, to protect the recovering meniscus. Rehab focuses on regaining full range of motion and functional progression without aggravating symptoms associated with the injury.6 A supervised rehab program has been shown to reduce the amount of time a patient spends on crutches and prevent losses in range of motion.10

Most rehab protocols contain three phases. Time frames, restrictions, and precautions are included in each phase to allow for tissue healing and recovery from surgery. While general time frames are typically given for reference, individual patients will progress at different rates.

Phase 1

Phase one aims to gradually wean a patient off of crutches while exercises aim to restore knee extension and leg control. This is considered a protective phase for the knee and typically involves a gentle range of motion and quadriceps exercises. Patients progress after 4-6 weeks when they can walk pain-free without crutches and the knee is no longer swollen.

Phase 2

Phase two aims to establish single-leg control and good biomechanics with functional movements, such as stairs and squats. Phase two consists of non-impact balance and proprioceptive drills, the use of a stationary bike, and strengthening of the core, hips, and quadriceps. Progression requires the ability to carry out functional movements with good control and without pain or unloading of the affected leg.

Phase 3

Phase three aims to develop neuromuscular control and tissue tolerance with sport-specific movements, including impact. Movement drills progress to higher velocity, multi-plane activities while strength and control drills become more difficult and sport-specific.

Conclusion

Patients who undergo non-operative management tend to have similar to better outcomes in terms of strength and perceived knee function compared to those who undergo APM.12 Current guidelines advocate for surgery only after a failed attempt at conservative treatment13 and there is currently no evidence to support the benefit of APM over non-operative management.

Young patients who have meniscus repair have similar to better perception of their knee function, lower levels of activity loss, and higher rates of return to sport when compared to those who have APM.

Whether a patient undergoes surgery or non-operative management, rehab is necessary to obtain the best outcomes. A structured rehab program improves symptoms, range of motion, muscle function, coordination, and reduces the risk of further injury.11

References

- Proctor CS, Schmidt MB, Whipple RR, Kelly MA, Mow VC. Material properties of the normal medial bovine meniscus. J Orthop Res. 1989;7:771–82.

- Morgan CD, Wojtys EM, Casscells CD, Casscells SW. Arthroscopic meniscal repair evaluated by second-look arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:632–7

- Baker BE, Peckham AC, Pupparo F, Sanborn JC. Review of meniscal injury and associated sports. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:1–4.

- Rubman MH, Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Arthroscopic repair of meniscal tears that extend into the avascular zone. A review of 198 single and complex tears. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:87–95.

- Bhattacharyya T, Gale D, Dewire P, et al. The clinical importance of meniscal tears demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging in osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85:4-9.

- Goldblatt JP, LaFrance RM, Smith JS (2009). "Managing meniscal injuries: The treatment". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 26 (12): 471–7

- Arthroscopic meniscal repair evaluated by second-look arthroscopy. Morgan CD, Wojtys EM, Casscells CD, Casscells SW Am J Sports Med. 1991 Nov-Dec; 19(6):632-7; discussion 637-8.

- Andersson-Molina H, Karlsson H, Rockborn P. Arthroscopic partial and total meniscectomy: A long-term follow-up study with matched controls. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:183–9.

- Eggli S, Wegmuller H, Kosina J, Huckell C, Jakob RP. Long-term results of arthroscopic meniscal repair. An analysis of isolated tears. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:715–20.

- Barber FA, Click SD (1997). "Meniscus repair rehabilitation with concurrent anterior cruciate reconstruction". Arthroscopy. 13 (4): 433–7.

- Jeong, HJ.; Lee, SH.; Ko, CS. (Sep 2012). "Meniscectomy". Knee Surg Relat Res. 24 (3): 129–36

- Naimark MB, Kegel G, O'Donnell T, Lavigne S, Heveran C, Crawford DC. Knee Function Assessment in Patients With Meniscus Injury: A Preliminary Study of Reproducibility, Response to Treatment, and Correlation With Patient-Reported Questionnaire Outcomes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(9):2325967114550987. Published 2014 Sep 23. doi:10.1177/2325967114550987

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A The FIDELITY (Finnish Degenerative Meniscal Lesion Study) Investigators, et al Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus placebo surgery for a degenerative meniscus tear: a 2-year follow-up of the randomised controlled trial Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2018;77:188-195.

.png)

.png)