Osteoarthritis or OA is a progressive joint disease that affects approximately 1 in 6 Canadians. Over the next 20 years, this number is expected to grow to 1 in 4, due to an aging population and increase in obesity rates.1 OA can cause joint pain, stiffness, loss of mobility, swelling, and crepitus or grinding noises. It typically affects hands and weight bearing joints including knees, hips, backs and feet, but can be found in other joints as well. OA is classified into two groups: primary and secondary. Primary OA is idiopathic, meaning there is no specific cause. Secondary OA is due to previous injury or trauma to the joint.2

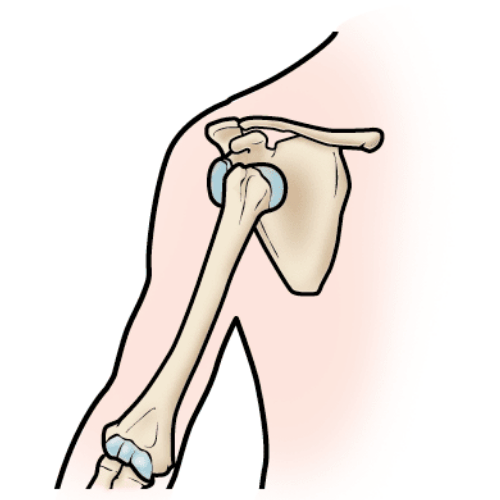

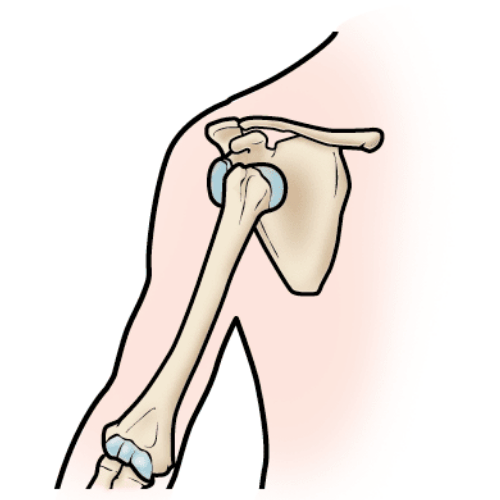

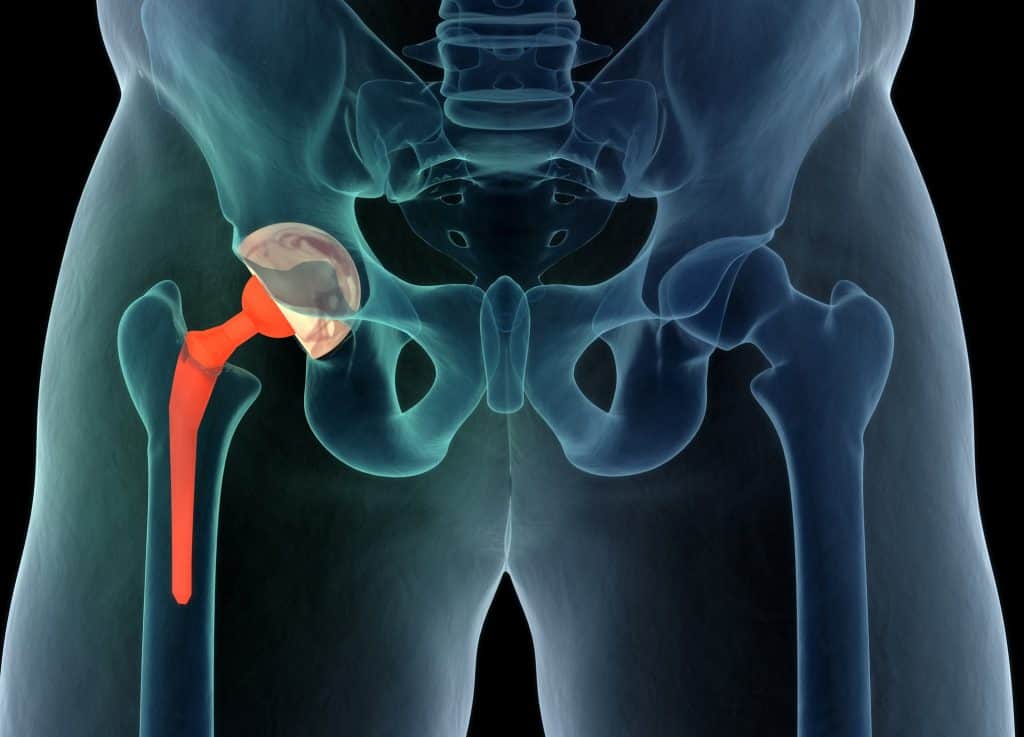

Picture your hip joint where the ball of your femur (thigh bone) fits into a socket or hollowed part of your pelvis. The ends of the ball and socket are made of subchondral bone, which is then covered in articular cartilage. This structure allows the joint to spin and rotate smoothly.

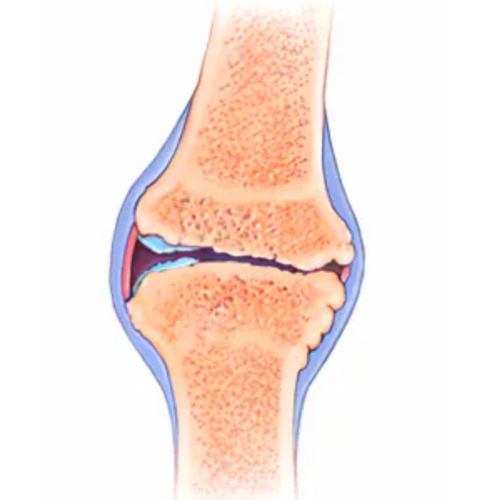

In a healthy joint, there is a balance between degradation (breakdown) and repair for all of the joint tissues. With OA, this equilibrium is lost and an imbalance causes more degradation than repair. Historically, changes in articular cartilage were considered the primary structure affected by OA, however it is now known that many other structures of the joint also undergo changes. Cartilage is a structure that has very little vascular (blood) and nerve supply. This means that in early stage OA, the cartilage alone is not capable of causing inflammation or eliciting a pain response to that area.2

Pain experienced mainly comes from changes in other areas of the joint including: the capsule and synovium or lining of the capsule where effusion or swelling can occur; the subchondral bone, where increased bone density can cause changes to the surface of the joint and extra bone growth called osteophytes; and the surrounding ligaments and muscles that can become more lax and weaken.3 It is not yet fully known what initiates this process of arthritic changes at the joint, but it is known that this is not normal ‘wear and tear’ due to age. While the incidence of osteoarthritis increases as we age, it is not considered a normal part of aging.4

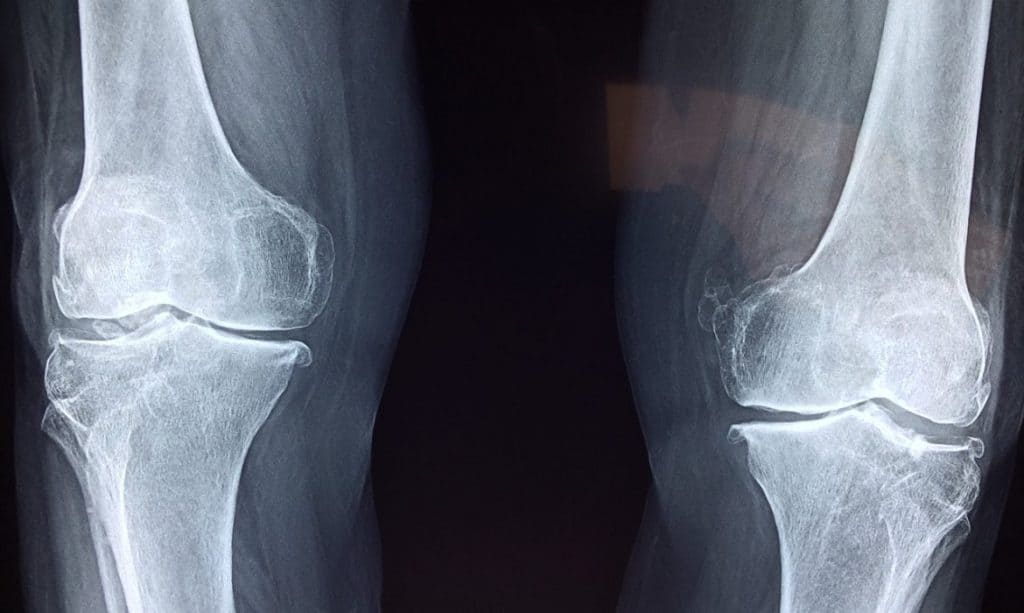

X-rays can show narrowing of the joint space and bone changes with osteoarthritis, but this does not necessarily correlate with one’s symptoms or clinical presentation. This means that a person with mild changes on imaging may experience lots of pain and decreased range of motion, while another person with severe osteoarthritis on imaging may have good function. The Framington Osteoarthrits Study found radiographic (x-ray) presence of OA in 27% of those participants aged 65-69 years old; however only 11% of women and 7% of men had symptoms of OA. As well, of those with severe changes on x-ray, only 40% were symptomatic.5 Imaging can be helpful to show joint changes, but must be correlated with a clinical presentation – your pain levels, movement, and ability to do the activities that you enjoy.

There are many different factors at play regarding whether a joint will develop osteoarthritis. These can be broken down into systemic and biomechanical risk factors.

Systemic factors are those that have an influence on your entire body. Non-modifiable systemic factors include ethnicity, sex, genetics, age and hormones. Obesity is one risk factor for OA that can be modified, yet obesity rates are on the rise. As of 2018, approximately 28% of Canadians had a height and weight that classified them as obese.6 This can lead to increased stress across joints, issues with circulation, and increased bone density.7 Obesity is also one condition that can contribute to metabolic syndrome, along with high blood pressure, high blood sugar, and high cholesterol, which together increase risk of heart disease and type II diabetes. Metabolic syndrome-associated osteoarthritis is characterised by these risk factors and chronic low-grade systemic inflammation. Studies have shown that in patients with knee OA, the presence of metabolic syndrome may actually increase the frequency and severity of symptoms, which means that controlling these risk factors may be able to slow the progression of OA.8 Interestingly, metabolic syndrome is also linked to other musculoskeletal problems such as frozen shoulder. Overall, systemic factors can put a joint at more risk for injury by impairing the repair process in a damaged joint, or by directly damaging the joint tissues.3

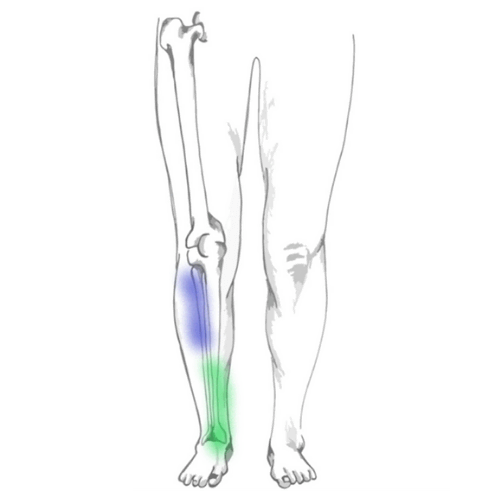

Biomechanical factors are those that influence how we move, and can be categorized as anatomical or functional. Anatomical refer to the physical structure of your body, as depicted by skeletal and muscle diagrams. Everyone has a slightly different anatomical structure, and it’s normal to see variability among different people, however there are some anatomical changes that can increase risk for development of osteoarthritis. Examples include valgus alignment of the knees (knock knees) or acetabular dysplasia (a shallow hip socket).9 Often these changes are congenital or present since birth, and cannot be altered without surgical procedures. The functional category is how our body reacts to the environment in which we place it, giving us more control over this category. This includes occupation, sport and physical activity, muscle strength, proprioception (awareness of how we move in space), and previous injury.3 Having a biomechanical risk factor does not automatically mean you will develop OA, but coupled with systemic factors, they can make a joint more vulnerable.

There are some myths that exercise can increase risk of developing OA, however this has been refuted in the literature, and in fact the opposite has been shown. It has been found that physical activity does not accelerate OA, but it can aid with weight loss and improve mood, as well as address associated risk factors by positively affecting cholesterol and glucose levels, and systemic inflammation.10,11 There appears to be a dose-response relationship with exercise and OA. Up to a certain point, the benefits of exercise outweigh any risk. However, with elite sports (e.g. soccer, wrestling and weight lifting) a higher risk of developing OA has been shown. With these sports it is not clear what components of the sport cause the increase in risk. It is postulated that OA may be more related to injuries and associated muscle dysfunction, rather than the sport itself.12 For example, one study shows athletes with ACL and meniscus tears have a 34% lifetime risk of developing symptomatic OA, compared to 14% of uninjured athletes.13 Overall, exercise of your choosing up to a moderate level should not increase risk of developing OA, provided that the exercise is the correct level for you and is performed safely.

The two interventions for OA with the strongest recommendations based on research are exercise and weight loss.2 Exercise therapy, or exercise designed for your specific function and goals, is considered a first-line treatment for OA, as it is safe and has high effectiveness for reducing pain, improving function, and preventing limitations in movement and daily activities. Furthermore, exercise therapy has been found to be as effective as NSAIDs (Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, i.e. Advil) and more effective than acetaminophen (Tylenol).14 Like medications, it is important to find the dosage of exercise that is correct for you. This includes the correct type, amount, duration, and frequency of exercise. Studies have found that land exercise has greater benefit than aquatic exercise, as it requires more weight-bearing of the joints; however aquatic exercise can be used effectively when weight-bearing exercises are too painful, or for cardiovascular benefits.15 OA can affect muscle strength, proprioception (spatial awareness), and joint stability, which can also be addressed through exercise.16 It can be difficult to initiate exercise when you have pain, however if exercise is correctly dosed, it should not exacerbate pain and over time can improve pain levels.17

Some pain relievers such as NSAIDs and Acetaminophen can help with pain associated with OA, however there is currently no drug proven to modify the disease process of OA.17 Corticosteroids are also sometimes used for painful OA. These can be helpful in the short-term, but studies have found that people who do physiotherapy have better outcomes at one year with pain and function than those who get an injection.18 Physiotherapy for OA focuses on tailored exercises, but can also include hands-on manual therapy to help with initial pain levels and function of the joints. Surgery is a great option for someone who has progressed to that stage. If this is something you are considering, check out our articles on hip and knee replacements.

In 2012, the Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative (COAMI) issued a call to action for a comprehensive care model for OA.19 Consider high blood pressure. This is something that is detected early on through blood pressure readings at doctor’s appointments, managed over time through medication and lifestyle changes like diet and exercise, and overall treated preventatively before a major issue such as a heart attack occurs. Now compare this to the treatment of OA, which is typically reactive care, often started after a person begins to experience pain and limitations in their daily function. A study looking at end stage hip OA in women found that approximately 30% of women in this category fall at least once a year, generally tripping forwards, and 13% of these falls result in fractures. Falls correlated with a limp and poor quadriceps (knee extensor) muscle strength, which can be detected early on and worked on preventatively.20

As discussed above, there are many risk factors and influences on joint health. For anyone who has systemic risk factors or has had a previous injury, preventative exercise should be considered. It can be difficult to know where to start and to find objective measures to track over time. At Kinetic Labs, we perform Baseline Movement Analyses which accurately depict joint range of motion, strength, and balance. This assessment can be used to determine any current issues, develop programs to improve these areas, and track your changes over time. With preventative measures, our goal is not to stop someone from ever developing OA, just as we cannot guarantee that someone managing their blood pressure will never have a heart attack. Instead, our goals are to optimize your body and your environment to delay this timeline. As well, we know that imaging findings of OA do not correlate well with symptoms, so even if joint changes begin to occur, preventative care can help to prolong and manage symptoms.