Adductor injuries, often encountered in sports, can be quite a challenge for athletes. These injuries occur when certain muscles in the groin region are strained during intense physical activity. Interestingly, researchers have found that among 25 different college sports, men’s soccer and men’s hockey have the highest rates of these injuries, making them more susceptible to such strains.

Even after seemingly recovering from an adductor injury, there’s a high re-injury rate. For instance, in professional soccer, about 18% of players experience a recurrence, and in professional hockey, that number rises to 24%.

Fortunately, the path to recovery and successful return to sports can be achieved with the right assessment and treatment from a specialized rehabilitation professional.

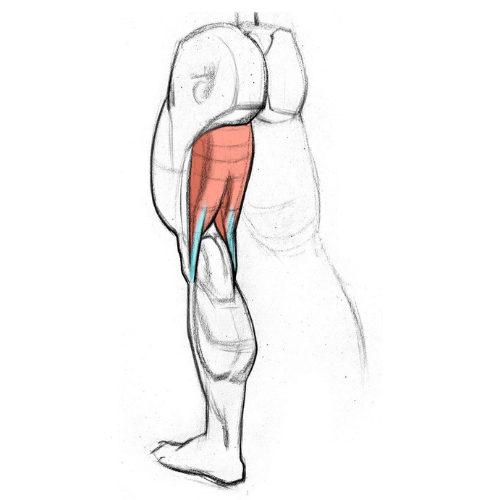

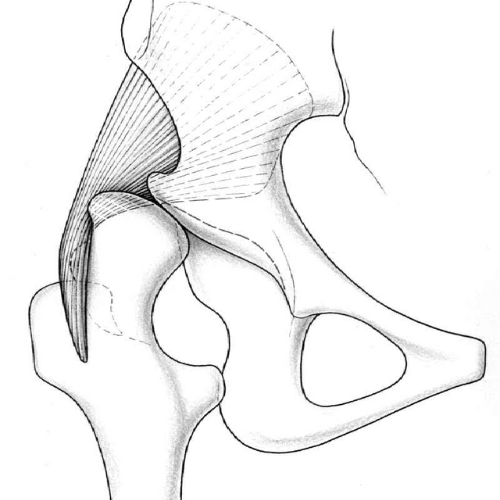

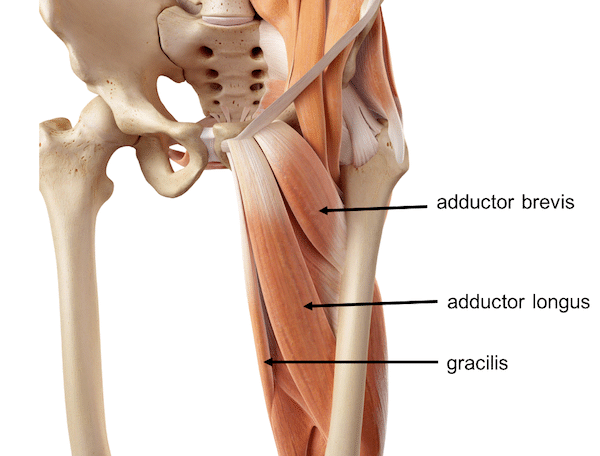

The adductor muscle group consists of six muscles that run along the inner thigh: adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, pectineus, gracilis, and obturator externus. These muscles are connected to the front and lower part of the pelvis. The obturator nerve controls most of them, except the pectineus, which is controlled by the femoral nerve, and part of the adductor magnus, which is controlled by the sciatic nerve.

As the name suggests, the main function of the adductor group is to bring the thigh towards the midline of the body (adduction). However, they also have other important roles, like stabilizing the trunk, aiding in flexion and extension of the thigh during running, and being involved in kicking a soccer ball with the inside of the foot. Additionally, depending on how the leg is positioned, the adductor muscles can also contribute to rotating the hip either outward or inward.

Although these muscles are usually talked about as a group, when it comes to groin pain related to adductor injuries, it’s often the adductor longus muscle that is the primary culprit.

Risk factors for groin injury in sport include:

Diagnosing and effectively treating adductor strains can be quite challenging due to the complexity of the pelvic region and the possibility of other related issues, such as hip-related pain. It’s crucial to distinguish adductor strains from other pelvic-related problems to ensure the right course of action.

Researchers have developed a classification system to categorize groin pain, which includes adductor-related, iliopsoas-related, inguinal-related, pubic-related, or hip-related conditions. However, these categories can sometimes overlap, making the diagnosis more complicated.

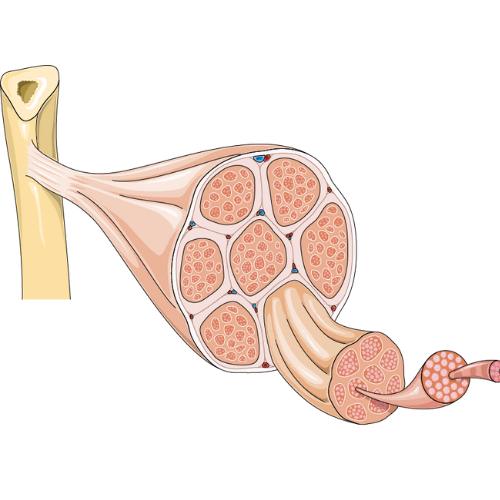

Adductor strains have a unique feature – they can develop gradually, causing long-lasting pain in the inner thigh. These strains may involve either the muscles or tendons, requiring different treatments for successful recovery.

To diagnose an adductor strain without imaging, your therapist considers the timing of symptom onset, the location of the pain, and the movements that trigger discomfort.

A typical presentation includes sudden pain in the adductor region during physical activity, leading to the athlete’s removal from the game. Tenderness in the adductor muscles during examination, worsening with resisted movements and passive stretching, is also common.

Timing of symptoms is important. Pain the day after activity with no symptoms during the activity itself suggests a muscle strain. Chronic or intermittent adductor-related pain indicates a possible tendon injury.

Location of symptoms during the examination can vary. Tenderness closer to the muscle insertion point may involve the tendons, while pain above the inguinal crease may suggest athletic pubalgia or related hernias.

To provoke symptoms, doctors perform resisted adduction (bringing the thigh in) and hip abduction (bringing the thigh out) tests. These help differentiate adductor strains from other conditions, like athletic pubalgia. Careful evaluation helps your therapist accurately diagnose and create a suitable treatment plan.

Treating adductor strains involves three phases of rehabilitation. Nonoperative treatment is advised and has a good success rate in helping athletes return to play with low re-injury risk.

The Copenhagen adductor exercise, primarily beneficial for preventing groin injuries, can also be helpful in adductor strain rehabilitation. It should be progressed carefully, starting with short muscle lengths and isometric contractions. As rehabilitation progresses, athletes can gradually move to more challenging exercises to improve muscle strength and function.

To assess readiness for return to sport and ensure complete restoration of the injured hip adductors, an objective assessment of hip adduction strength is essential. Comparing strength between the involved and noninvolved sides and between the hip adductors and abductors is crucial. Unilateral testing is important to overcome limitations in bilateral testing, which can lead to inaccurate results. Testing both hip adductors and abductors is vital to restore balance between these muscle groups, as weak adductors relative to abductors can increase the risk of future adductor strains.

When an athlete can perform sports-specific functional testing without any symptoms and at a performance level similar to uninjured peers, and they have normal hip adduction strength (within 10% of the noninvolved side and 10% of the hip abductors on the same side), the risk of re-injury upon return to play is low. These objective criteria help athletes feel more confident about returning to sports without fear or avoidance.

McHugh, M. P., Nicholas, S. J., & Tyler, T. F. (2023). Adductor Strains in Athletes. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 18(2). https://doi.org/10.26603/001c.72626