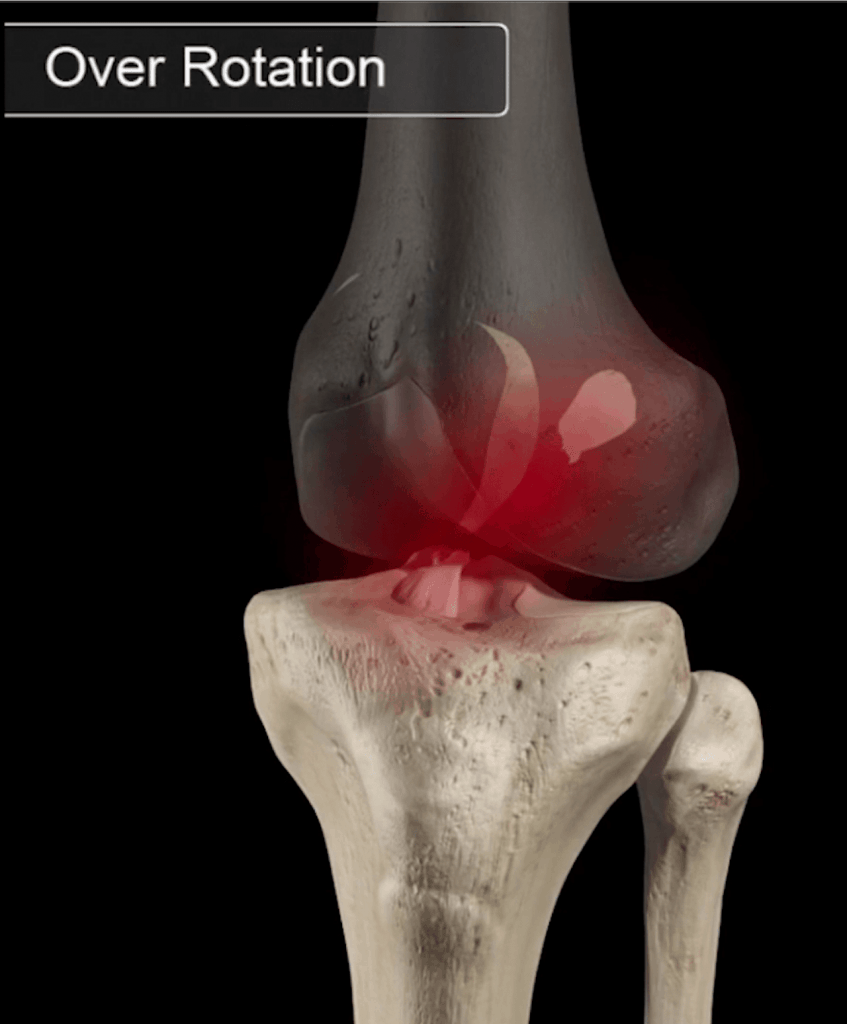

How does an ACL tear happen?

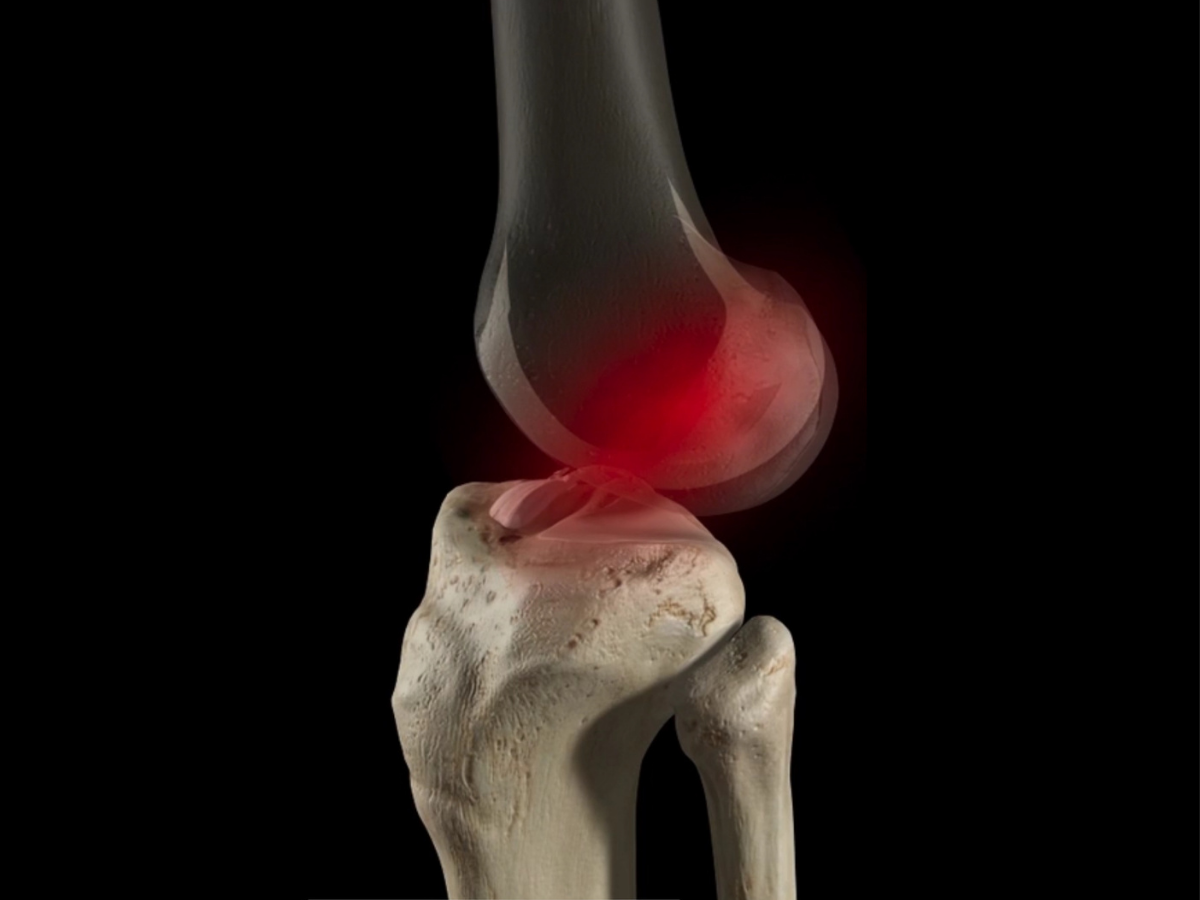

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) tear is a common injury with an estimated 200,000 occurring each year in the US.1 The ACL connects the bottom end of the femur (thigh bone) to the top end of the tibia (shin bone) in such a way that it helps prevent the lower leg from moving forward relative to the thigh and from twisting inwards towards the midline. An ACL tear can have significant effects on the way your knee moves, with instability typically being the primary problem. ACL reconstruction (ACLR) surgery aims to surgically recreate the anatomical function of the ACL, however there is a growing body of evidence that surgery is not the only option.

Do I need surgery for an ACL tear?

Previous theories favoured ACLR over conservative management due to a belief that reconstruction would prevent development of osteoarthritis (OA) in the knee and further meniscal damage. More recent research has since debunked this, showing that ACLR does not show decreases in OA at 20 years post-surgery and that OA changes are 4-6 times more likely to occur in the 10 years following an ACL tear regardless of treatment choice.2,3,5 Additionally, there has even been research showing that a torn ACL can actually heal over time.4

After a period of rehab involving intense strengthening, neuromuscular control, balance, and sport specific training, some people are able to recover from the initial injury and are able to function normally without an ACL (referred to as copers). One of the most famous examples of this is DeJuan Blair, who managed to play 8 seasons in the NBA with no ACL in either knee.

Other patients continue to have episodes of knee instability (referred to as non-copers). Non-copers may be able to function in normal daily activities without an ACL, however high-demand sporting activities (cutting, pivoting, sudden turns) may prove to be difficult, and it is thought that for non-copers ACLR is necessary to stabilize the knee.

Knowing that surgery may not be necessary, here are some of the questions that need to be considered before making a decision:

• Have you done a period of supervised rehab?

• Are you experiencing knee instability?

• Are you trying to return to a sport that requires cutting/pivoting/sudden turns?

• What kind of commitment are you able to make to your rehab?

While the last point may look a bit out of place, it’s as important of a consideration as the first three. Recovering from an ACL reconstruction surgery is not an easy process. It takes months of dedicated rehab and hard work. As such, it’s critical to ensure you are able to create space in your life to commit to the rehab process. While I’m lucky enough to live in a country where surgery is covered by health insurance, the cost of medical equipment (crutches, cryocuff rental), physiotherapy, and time off work to recover from surgery can quickly add up, meaning that surgery also requires a significant financial commitment.

Current clinical guidelines state that a period of rehabilitation should always be offered prior to surgical reconstruction. Research has shown that this prehab phase can reduce ACL surgery by up to 50%, and after this, if someone is still struggling with instability then surgery remains an option.6

Should I do prehab before ACL surgery?

For those who do decide to get surgery, I would argue that comprehensive prehab is the most important thing you can do in preparation. Most surgeons prefer to wait until swelling resolves to perform an ACLR and this can take several weeks. So, it is a perfect time to prepare for surgery, build up the capacity of your muscles to minimize the effects of the injury and prepare mentally for post-op rehab. Research has demonstrated a six-week prehab program results in better objective knee function as well as self-reported measures of knee health.7

Most prehab protocols aim to eliminate swelling, regain full range of motion, eliminate any limping, and regain strength in the ACL-deficient leg. It has been shown that patients lacking knee range of motion prior to surgery have greater difficulty restoring range of motion after surgery. As such, achievement of full knee motion should serve as a critical milestone before surgery. Quad strength is another major factor. Patients showing strength deficits greater than 20% pre-operatively (compared to the other leg) had reduced strength at six and nine months post-operatively, demonstrating that there must be a strong emphasis on strengthening the leg before surgery.8

Surgery for a torn ACL

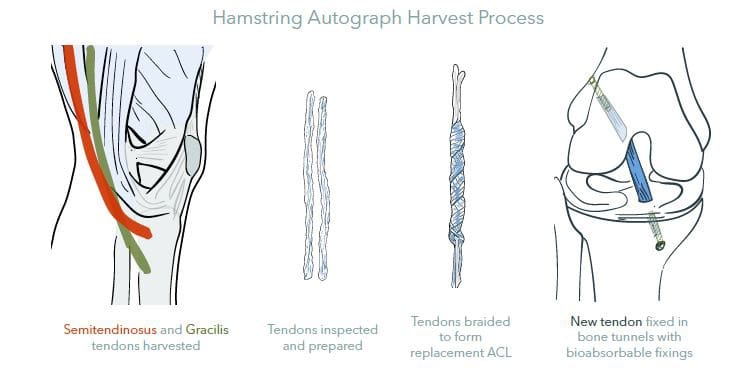

ACLR involves removing the damaged ACL and replacing it with a muscle tendon. Tunnels are made in the shin and thigh bone and the graft is passed through these tunnels to “reconstruct” and secure the ligament in place. The graft is typically made from either hamstring tendon, patellar tendon, or donor tissue (other grafts such as quadriceps tendon are used but less commonly so). While most surgeons will prefer one type of graft over another, there is currently no scientific evidence pointing to one as superior than the others as they all come with their pros and cons.

Patellar tendon grafts closely resemble the ACL and having bony attachment sites included in the graft allows for “bone-to-bone” healing which is often considered to be stronger. However, removing 1/3 of the patellar tendon for the graft does increase the risk of future patellar tendon problems as well as commonly being associated with pain in the front of the knee. Patients may have complaints of this pain, especially when kneeling, even years after the surgery.

Hamstring tendon grafts have a smaller incision to obtain the graft and do not have the same bone removal as patellar tendon grafts. As a result, the pain in the immediate post-op period as well as down the road tends to be lower. However, the lack of bone-to-bone healing results in the graft needing a longer period to become rigid and therefore requires a longer protective period.

The use of donor tissue or allograft allows for a shorter operating time, no need to remove other tissue for the graft, smaller incisions, and less post-operative pain. However, these grafts are weaker than if the patient had used their tissue for it. For many patients, the strength of an allograft is sufficient to meet day-to-day demands and therefore makes it an excellent option for non-copers who are not planning to participate in high-demand sports.

Recovering from ACL surgery

Following surgery, the long road of recovery begins. Progressive rehab allows the graft to slowly be worked into place within the knee. The slow progression of exercises and early protective phases allow the body to gradually cement the graft into place. In the first 2-4 weeks, the risk of the graft being pulled out of place is high because it has not yet been incorporated into the graft site.9 After about four weeks, the graft is more solidly in place, however, it is remodeling on a cellular level to become more like a ligament. As a result of this, the graft is mechanically at its weakest around 6-12 weeks post-operatively. Coincidentally, people start feeling a lot better around this point and are keen to do a lot more, making this one of the highest risk times for re-rupture. Here, there is a delicate balance between maintaining load in the knee and the muscles but doing so without compromising graft integrity.10

The final “ligamentization” phase involves continuous remodeling of the healing graft as it becomes more and more like an intact ACL. A clear endpoint is not known, but changes have been observed years after reconstruction. Changes to blood flow and collagen organization appear to cease between 6 and 12 months and mechanical properties of the graft improve substantially during this phase, reaching their maximum at around one year.11

Current best practice in rehab suggests the use of criteria-based protocols, meaning that someone can only graduate through each level of therapy when they’ve proved they are ready to, rather than based on a strict schedule. Regardless, the above shows that tissue healing times need to be respected, and as such a minimum of nine months is suggested before returning to sport. Research shows that for every month that return to sport was delayed (up to nine months) there was a 51% reduction in injury.12

Do I need to wear a knee brace after ACL surgery?

The use of a knee brace following an isolated ACL tear remains controversial (cases where there is additional damage to other structures in the knee such as the meniscus or MCL require different management). Many surgeons recommend the use of a brace during the initial 3-6 weeks following surgery with the thought that it will reduce pain, protect the graft, or maintain knee extension, however there is some concern that immediate bracing post-op may not be necessary, or further that it may pose a risk of harm due to muscle atrophy and associated losses in function and proprioception.13 Additionally, a 2013 study comparing those who did and did not use a knee brace post-operative found no differences in ligament integrity or injury rate, and the patients who did not use a brace after surgery reported less pain during sports or heavy physical work activities.14

Returning to sport after an ACL tear

Once you’re out of the early protective phases of ACL rehab and have demonstrated sufficient healing, strength, balance, and control, your rehab should begin to include sport-specific drills. ACL rehab must be highly individualized – it is not enough to just have a strong and stable knee at the end of rehab. People need to feel confident and mentally ready to return to their specific sport and this only comes from practicing those specific movements.

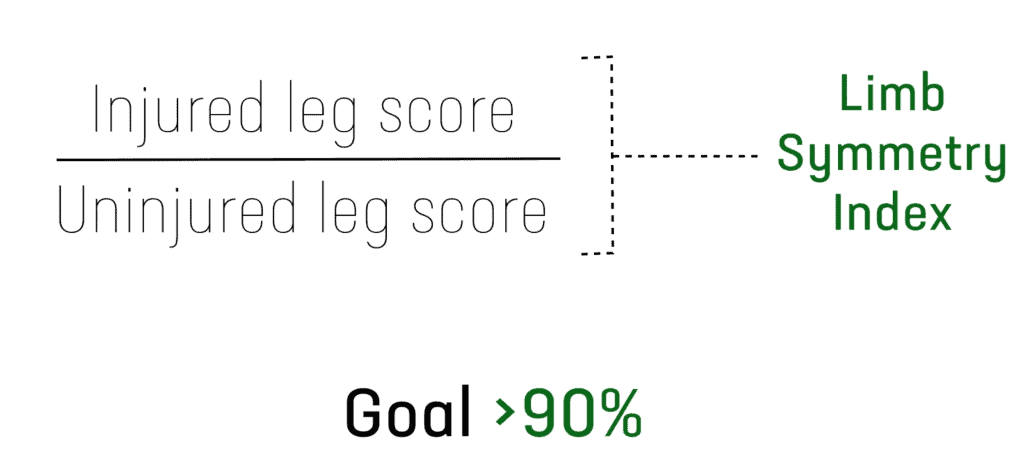

Common return to sport criteria include (but are not limited to):

- Strength within 10% of the other leg.

- Hop tests within 10% of the other leg.

- Confidence in running, jumping, and cutting at full speed (as well as with other sport-specific movements).

- No functional complaints.

A 2016 study12 used these criteria to assess the outcomes of 106 competitive athletes post ACLR and they found the following:

- 38% of athletes who returned to sports despite not meeting the criteria re-injured their ACL.

- Of the players who re-injured their ACL, 39% of them did so earlier than nine months.

- Four of the athletes tried to return in under five months (against medical advice), all four re-injured their ACL within two months.

- 5% of athletes who did meet all criteria re-injured their ACL.

Conclusion

Recovery from an ACL injury needs to be highly individualized. Two people with the same injury may have very different rehab programs based on what kind of activities they are aiming to return to and how their body copes with the injury.

A period of rehab should always be done after an ACL tear. ACL reconstruction surgery is indicated for those who want to return to high-risk activities but still struggle with functional instability after a period of supervised rehab.

For those that do get surgery, a minimum of nine months and successful completion of return to sport testing is associated with the lowest risk of re-injury.

References

- Spindler, K.P. and R.W. Wright, Clinical practice. Anterior cruciate ligament tear. N Engl J Med, 2008. 359(20): p. 2135-42.

- Filbay SR, Grindem H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019;33(1):33‐47. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2019.01.018

- van Yperen, D. T., Reijman, M., van Es, E. M., Bierma-Zeinstra, S. M. A., & Meuffels, D. E. (2018). Twenty-Year Follow-up Study Comparing Operative Versus Nonoperative Treatment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Ruptures in High-Level Athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(5), 1129–1136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546517751683

- Costa-Paz M, Ayerza MA, Tanoira I, Astoul J, Muscolo DL. Spontaneous healing in complete ACL ruptures: a clinical and MRI study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(4):979‐985. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1933-8

- Sanders, T. L., Kremers, H. M., Bryan, A. J., Fruth, K. M., Larson, D. R., Pareek, A., … Krych, A. J. (2016). Is Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Effective in Preventing Secondary Meniscal Tears and Osteoarthritis? The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(7), 1699–1707. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546516634325

- Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, et al Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial British Journal of Sports Medicine 2015;49:700.

- Shaarani, S. R., O’Hare, C., Quinn, A., Moyna, N., Moran, R., & O’Byrne, J. M. (2013). Effect of Prehabilitation on the Outcome of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 41(9), 2117–2127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546513493594

- Logerstedt D, Lynch A, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Pre-operative quadriceps strength predicts IKDC2000 scores 6months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee 2013;20(3):208-212.

- Goradia VK, Rochat MC, Grana WA, et al. Tendon-to-bone healing of a semitendinosus tendon autograft used for ACL reconstruction in a sheep model. Am J Knee Surg. 2000;13:143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffler SU, Unterhauser FN, Weiler A. Graft remodeling and ligamentization after cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:834–842. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0560-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen RP, Scheffler SU. Intra-articular remodelling of hamstring tendon grafts after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(9):2102–2108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, et al Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:804-808.

- Hiemstra LA, Veale K, Sasyniuk T. Knee immobilization in the immediate post-operative period following ACL reconstruction. Clin J Sport Med 2006;16(3):199-202.

- Mayr, H.O., Stüeken, P., Münch, E. et al. Brace or no-brace after ACL graft? Four-year results of a prospective clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 22, 1156–1162 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-013-2564-2

.png)