Tendinitis, tendinosis, tendinopathy?

Historically, tendonitis has been the term used to describe tendon pain; however, ‘itis’ refers to inflammation and over time, studies have shown that inflammation is not present in many tendon dysfunctions. While tendinitis can occur from an acute overload of a tendon, many tendon injuries do not fit into this category.1 Tendinosis, ‘osis’ to denote an abnormal process or condition, refers to a degenerative process happening in the tendon. Both tendinitis and tendinosis indicate specific pathology or structural changes happening at the tendon level, which cannot be seen by the naked eye. More importantly, even with imaging such as ultrasound and MRI, these changes to the tendon cannot accurately predict the symptoms that someone will experience.2 There are many cases of severe tendon changes on imaging in which a person is asymptomatic, and others where there are mild changes on imaging, yet that person experiences intense pain and loss of function. Since pathology does not accurately predict someone’s function, we use the term tendinopathy. ‘Pathy’ being derived from the Greek ‘pathos’, meaning “suffering or disease”, making tendinopathy the umbrella term used to describe the clinical presentation of tendon dysfunction and pain.3

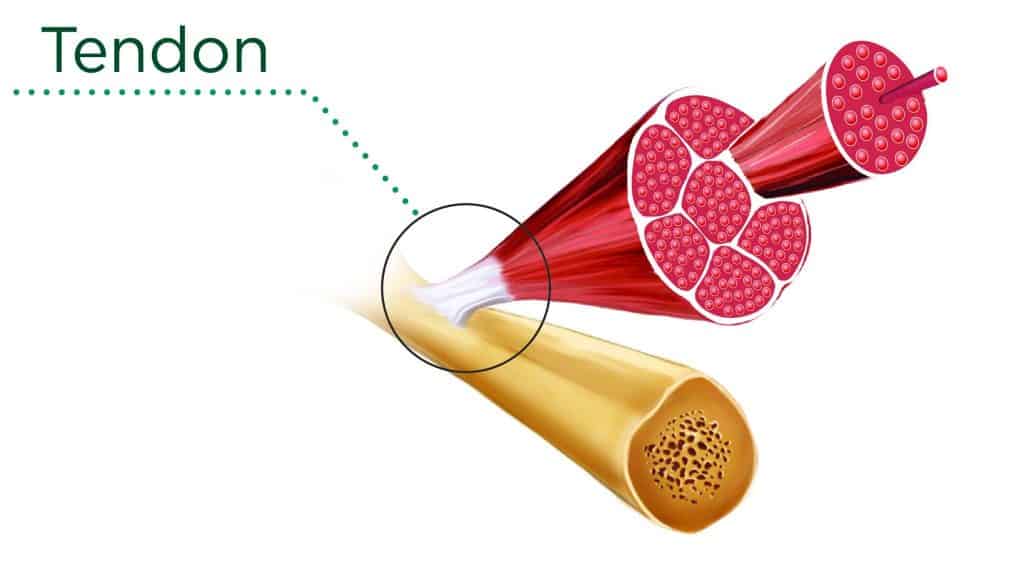

What are tendons?

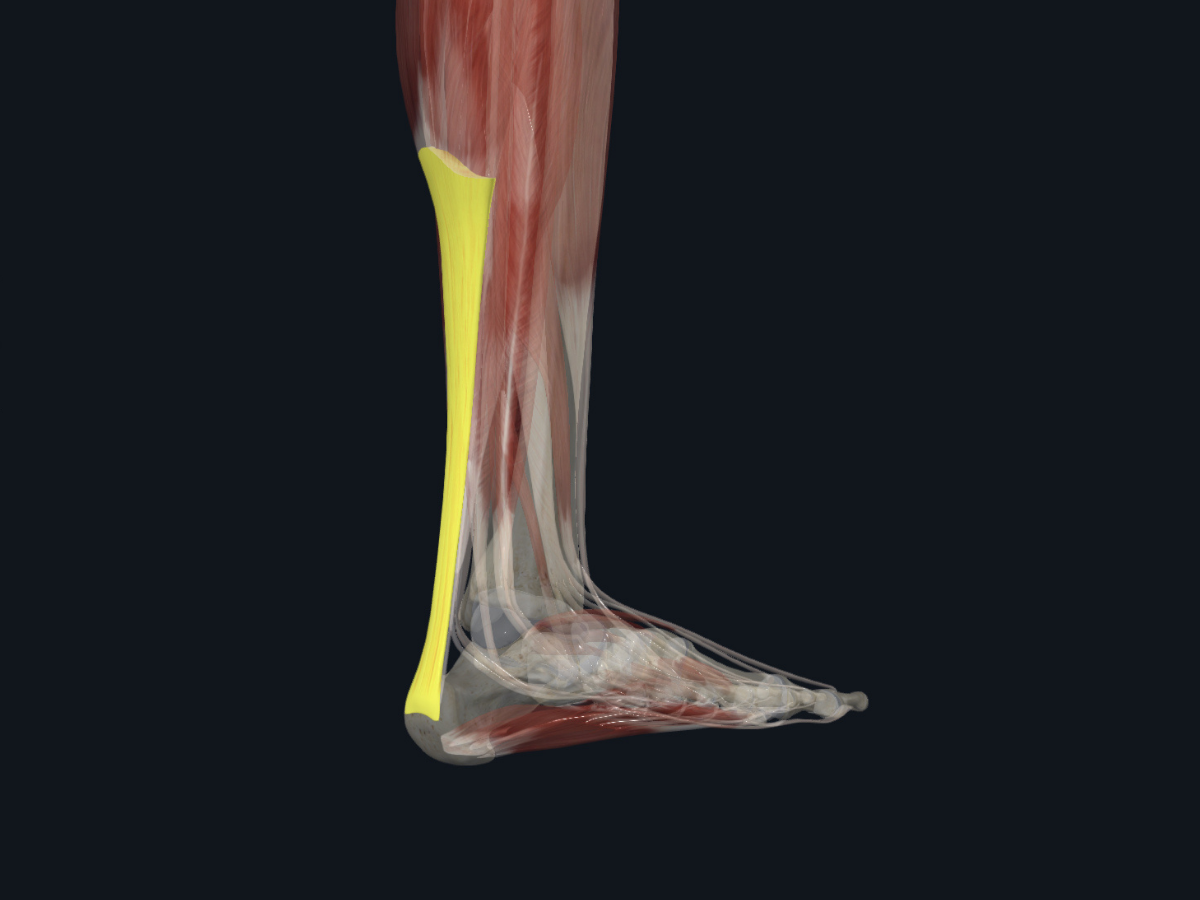

Tendons are the structures that connect muscle to bone. Their job is to transmit the force generated by a contraction of muscle to the bone to help produce movement. Tendons also help create temporary energy storage and absorb forces to prevent muscle overloading. Tendons have high tensile strength, which makes them work like elastics.4

Consider a jumping motion. As you squat down to prepare to jump, the patellar tendon (just below your kneecap) stretches. As you jump it shortens very quickly to help produce the movement, and as you land it stretches again to help you absorb the impact and land smoothly.

What is tendinopathy?

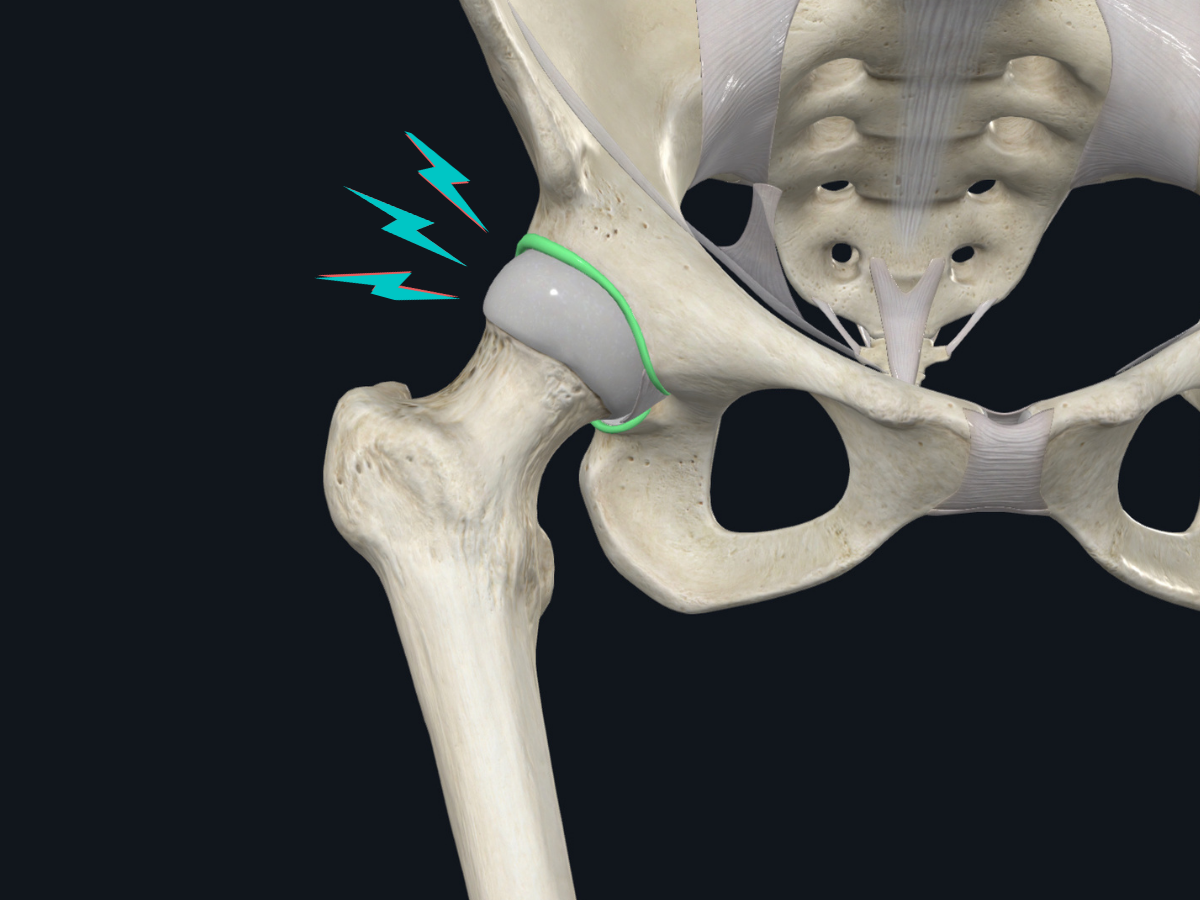

Tendinopathy is thought to occur when the tendon is unable to adapt to the load placed upon it. Mainly, this load is tensile in nature as described above, however it can also be compressive or frictional. Compressive loads occur where tendons pass over bony areas near joints.5 For example, where the Achilles tendon meets the bone at the heel it can be compressed with repeated dorsiflexion (toes towards nose motion). Frictional or shearing forces can occur with repetitive motions from the friction between the tendon and the sheath or covering around the tendon. If both compressive loads and increased tension are placed on the same tendon concurrently, this can potentially be more damaging.5

Tendinopathy usually occurs gradually over time from repetitive overload to the tissues, but it can occur suddenly from one instance of too much load. It can cause symptoms such as pain, stiffness, loss of strength, loss of movement, and localized tenderness to touch. Pain often occurs with specific movements involving the tendon, and can sometimes persist after being irritated.

What are the risk factors for tendon pain?

There are certain factors that are associated with an increased risk of tendinopathy. External risk factors include those that are determined by the environment we put ourselves in. This includes an individual’s sports, activities, and training programs. These risk factors can be controlled by avoiding any large spikes in load, so as not to overload the tendons. We will discuss this more later on with respect to exercise and treatment.

Intrinsic risk factors are those that pertain to the physical aspects of our bodies. Some of these we have the ability to modify, while others, such as age, sex and genetics, we cannot change. Let’s consider a ten-year-old versus a 40-year-old basketball player. If the repetitive loading that occurs is beyond the tissues capabilities, the 10-year-old is likely to experience Osgood-Schlatter Disease, a painful bump just below the patellar tendon where the tendon pulls on the bone at the growth plate. On the other hand, the same mechanism in the adult will likely irritate the tendon before the bone and result in patellar tendinopathy (also known as jumpers knee). As we age, it is normal to experience some changes in tendon structure, and injury will occur at the weakest link.

Certain lifestyle factors, systemic and autoimmune conditions, such as smoking, gout, abdominal obesity, rheumatoid arthritis, and type II diabetes can all negatively affect tendons.5 As well, increased low-density lipoprotein (bad cholesterol) has been shown to impair type I collagen production, which can reduce tendon strength.6 Studies have also shown that some medications, such as statins, steroids, and floroquinolones have been found to increase risk of tendon injury. Floroquinolones are common antibiotics used to treat infections, and research has shown that they can compromise tendon function and increase risk of injury for up to six months after taking the antibiotics.7

What does imaging tell us?

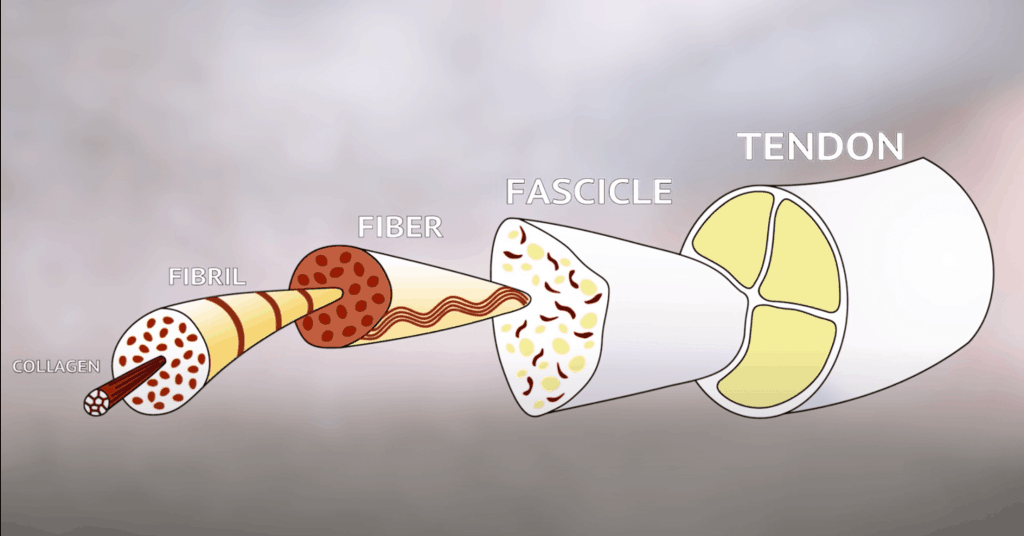

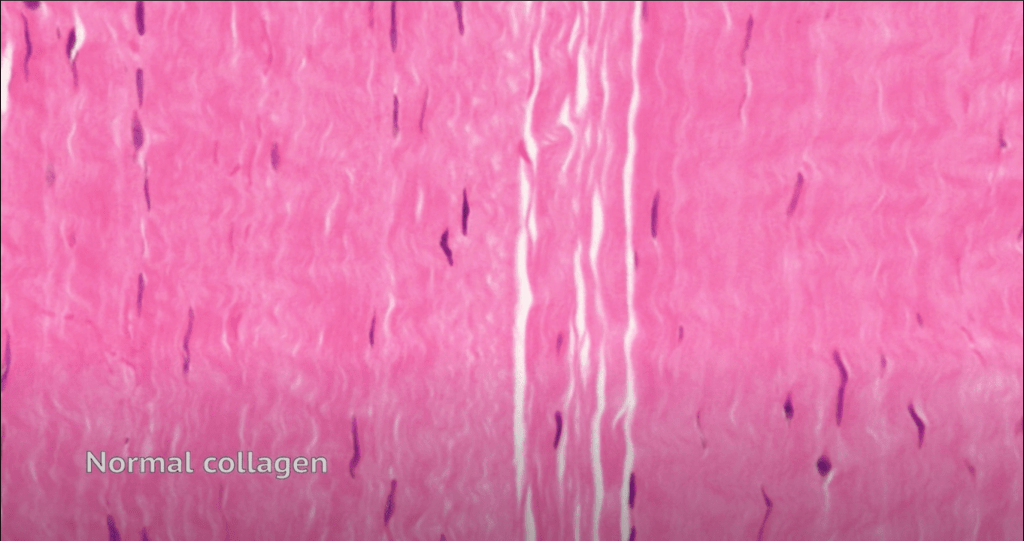

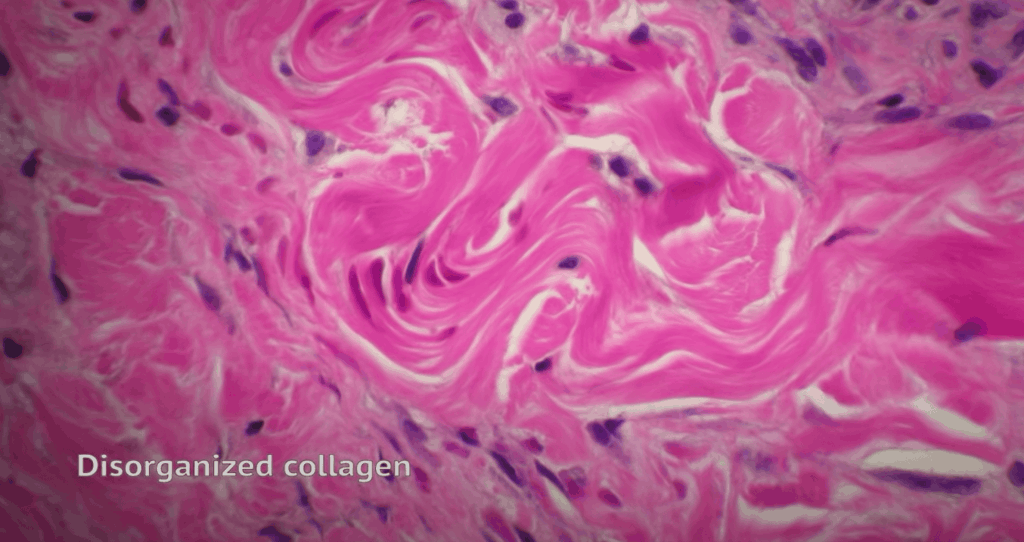

The structure of tendons can help to explain the properties that tendons exhibit, and what changes occur with injury. The main component of tendons is type I collagen fibres, which are aligned in parallel rows called fascicles and help to give tendons their tensile strength. Fascicles are then surrounded by the extracellular matrix, mainly composed of water and proteins called proteoglycans.8

It is not fully understood how negative changes, or pathology, in tendons develop. Current hypotheses suggest that tendon overload results in cell activation and increased proteoglycans, which leads to disruption of the collagen alignment. Picture a healthy tendon as raw spaghetti, neatly aligned in perfect rows, while an injured tendon resembles cooked spaghetti that is kinked and not as tightly bound. That change in structure accounts for loss of ability to transmit forces. As well, there is an influx of water to the area due to the changes in structure, which can give the appearance of swelling and tendon thickening, however this is not a true inflammatory response of the body.8

Both ultrasound and MRI are accurate in showing these tendon changes, but this does not necessarily correlate with how someone is feeling. While it is true that a symptomatic person will exhibit tendon changes on imaging, the opposite, that someone with no symptoms will have a normal tendon on imaging, does not hold true. A study looking at Achilles tendons in male long distance runners found that almost half (46%) of asymptomatic runners had pathological tendon changes on imaging.10 Therefore, pathology can be considered a risk factor for developing tendinopathy, but pain and symptoms do not correlate directly with imaging findings.2 From this perspective, imaging is not always needed. More important are the symptoms that one exhibits, or their clinical presentation.

So how do we diagnose and treat tendon injuries without imaging?

Clinically, we divide tendinopathies into two categories: reactive and degenerative.11 Reactive tendinopathies may be your diagnosis of Achilles tendinitis or jumper’s knee that only flared up a week ago. During this stage of tendinopathy, it is possible for the tendon to return to its normal structure with some treatment. Initial focus is on pain relief and temporary unloading of the tendon. Then, once symptoms have lessened, a gradual return to exercise. During this initial reactive stage, continuing to overstress the tendon can play a role in development of degenerative pathology. There are also some studies that show under-stimulation of tendon cells (too much rest) may also lead to degenerative changes.11

Degenerative tendinopathies can include diagnoses such as rotator cuff tendinitis or tennis elbow that have been painful for months to years. With degenerative tendinopathies, there is part of the tendon in which cell death occurs. This part of the tendon is unable to transmit load and does not have the ability to return to its normal function, which can potentially put too much stress on the healthy tendon.12 Although the tendon may not fully repair, this does not mean that symptoms cannot be addressed and resolved. Studies have shown that the healthy part of the tendon can compensate for the damaged area by increasing in size to help the tendon manage load placed upon it.13

Picture a tendon at this stage as a doughnut. Instead of trying to fill the hole, we focus on optimizing the rest of the doughnut. To do this, we focus on gradually increasing the amount of load the tendon can tolerate by slowly progressing exercise. As long as we do not overload the tendon too much, it will adapt and become more resilient.

What can I do for tendon pain?

The majority of people who seek out treatment for tendinopathy do so because of pain. There are some interventions that have been shown to reduce pain in the short term, such as NSAIDs, corticosteroid injections, and extracorporeal shockwave therapy, however the long term results are questionable and if interventions are directed solely at pain it may result in recurrence of pain in the long term.11 This is because these short term solutions alone do not address the muscle strength and function that are associated with disuse due to pain.13

What treatment helps long term?

Exercise based rehabilitation is the most researched treatment for tendinopathy. It may seem counterintuitive- why would you do the very thing that, for many people, caused this issue in the first place? But, like everything else in life, tendons require balance. Too little - it won’t improve, too much - it could get worse. These are the principles that we use with exercise.

There are two common exercise patterns that we see in people with tendinopathy:

Example one: When you run your Achilles hurts, but as you continue to run it starts to feel a bit better, so you keep going. The next day, it's sore in the morning and painful to walk, but you push through, and the next day go on another run. Then the cycle continues to repeat. We call this overload.

Example two: You go on a 5k run and part way through you start to get a nagging pain in your Achilles, so you stop for two weeks. Two weeks later, you try running a 5k again, and the exact same pain happens, so you rest again, and the cycle continues. We call this stress shielding.

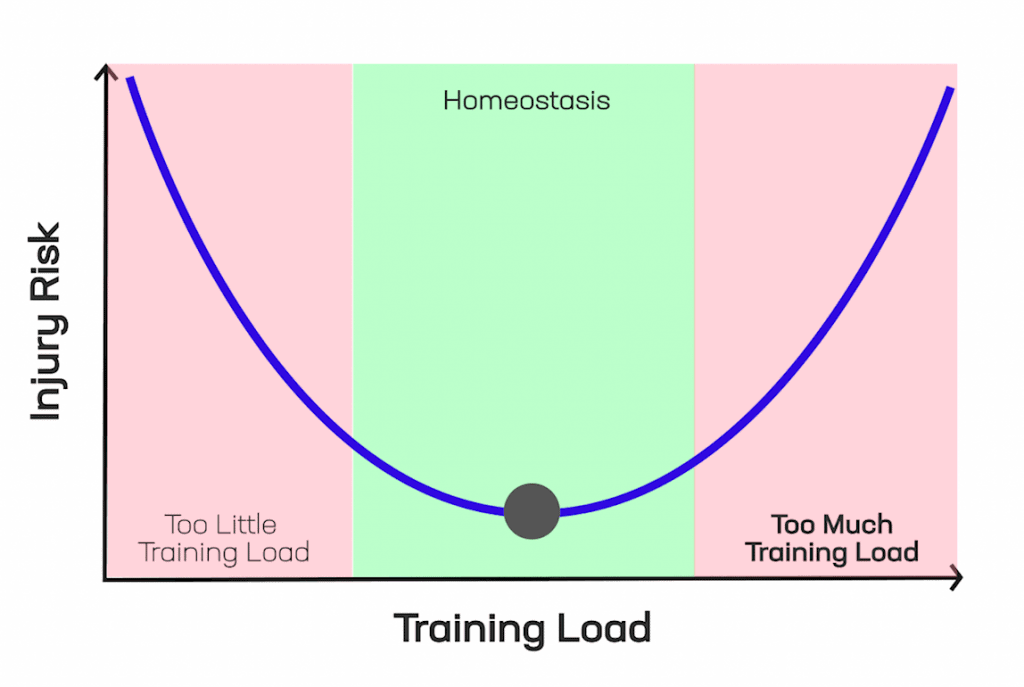

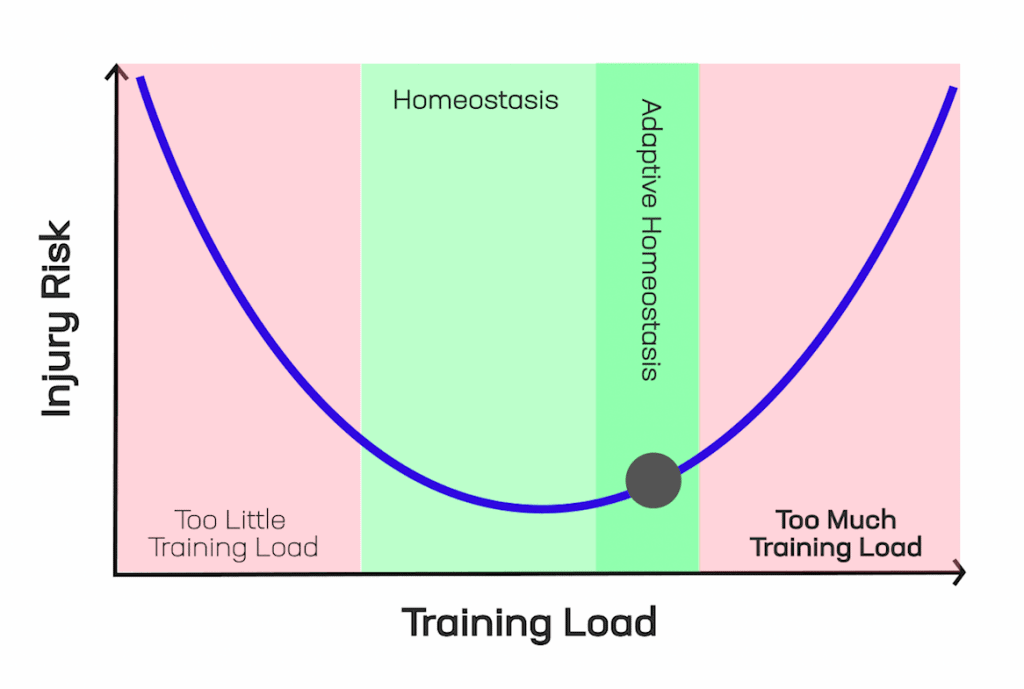

These two scenarios are at opposite ends of the spectrum. Overloading where the training load exceeds the capacity of the tissues, in this case the tendon. If you continuously subject a tendon to too much load repetitively, it will not have the chance to adapt and repair itself. The second, stress shielding, which can initially help to begin the healing process of a reactive tendon. However, rest can only get you so far, and if you rest too much then go back to the same activity, the tendon will still not be able to tolerate it. In this case the training load is way less than what the tissues/tendon are capable of, then with abrupt return to exercise once symptoms lessen, the opposite occurs with an acute tissue overload. Stress shielding can also have a negative effect on other muscles, joints, and cardiovascular system, which have now all had breaks from exercise as well.

Where we want to focus for tendon healing, and improvements in performance for healthy tendons, is the middle of the spectrum - homeostasis. Homeostasis is the point where the training load is equal to the current capacity of the tendon. At the beginning of an Achilles injury, this might mean taking a break from running, but biking to keep up cardiovascular endurance, and strength training to load the Achilles. Once symptoms are lessened, we can then move into the adaptation stage. Loading the tendon a bit more each time, but not to the point of overload. This is the small window in which the tendon can adapt positively to the change in load and heal to make itself stronger and more resilient.

What type of exercise should I do for tendinitis?

Each individual will have a certain starting point based on what amount and type of exercise provokes their pain or symptoms. After this starting point is established, a progressive exercise program is developed with the focus on achieving movement goals. These progressions are based on the structure and properties of tendons, beginning from low stress to high stress movements.

When tendons are painful, we start with isometric exercises, which involve static prolonged holds of a movement, for example a wall sit. Isometric exercise is one intervention that has been shown to induce immediate analgesia or pain relief in some tendons, and also help maintain strength.14 As pain and symptoms lessen we progress to slow isotonic movements, such as a squat, and gradually add resistance.

For a long time, research focused on eccentric loading for tendinopathy, which is strengthening the muscle during its lengthening phase (e.g. for a calf raise, the descent of lowering your heels back down to the ground). However more recent research has shown that heavy slow resistance training facilitates better outcomes.5

Eccentric exercise is still very helpful during rehab to progress exercises without flaring symptoms and for sport specific movements, but it should not be used in isolation. Performing exercises slowly is important when we consider the structure and function of tendons. As discussed earlier, tendons have elastic like properties, so quicker movements will involve higher stress.

Tendon Neuroplastic Training adds an external cue using a metronome to help pace exercises. This keeps speed consistent for the duration of the exercise and has also been found to improve motor control, the signals from the brain that help to control muscle impulse, which is altered with tendinopathy.15 Finally, rehab focuses on a gradual increase in speed and impact of movements to help return individuals to their sports and activities.

What if I have pain during exercise?

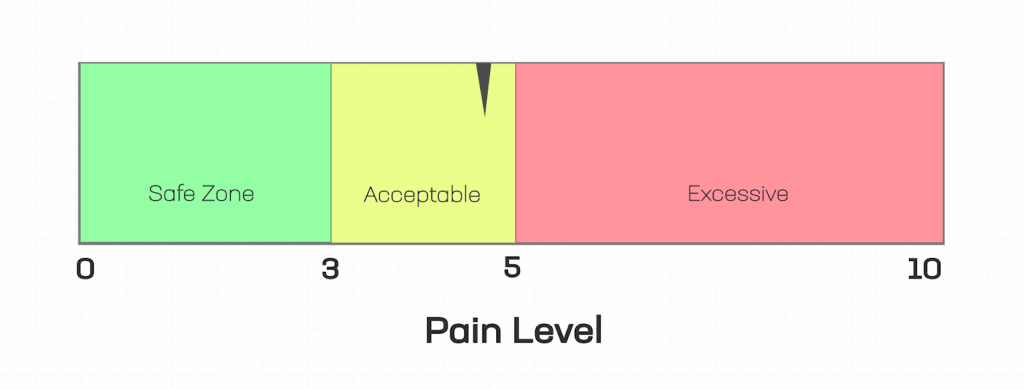

The saying “no pain, no gain” does not always hold true when it comes to rehabbing an injury. Sometimes too much pain can be a sign that you are overloading the tissues, other times it means that your nervous system feels threatened by the movement. Either way, our end goal is to decrease pain, not make it worse. The Numerical Pain Rating Scale is a ruler from 0 – no pain, to 10 – the worst pain you can imagine. This can be split up into three sections like a traffic light:

Green light (0-3): A little bit of discomfort during your exercises is ok. This pain should dissipate soon after completion of the exercise.

Yellow light (4-5): This is a sign that you are pushing your body towards its limit. If the pain is not subsiding after completing your exercises, or if you feel worse the next day, this can be a sign that you are not recovering well from your exercises. In this case, reduce your load until you are back in the green zone.

Red light (6-10): Intense pain during or after your exercise is a sign that your body is not adapting well to the stress you are placing upon it. Exercising repetitively in this zone can cause injuries to persist for longer.

What does all of this mean for my recovery?

Tendinopathies can be difficult injuries to heal and unfortunately, there are no quick fixes. However, with some guidance and exercise, many people have great outcomes and can return to the activities and sports that they love. At Kinetic Labs, we treat people of all ages and activity levels with tendinopathy. If you are experiencing tendon pain, reach out to us and we can help you return to an active lifestyle.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3312643/

- https://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.2015.5880

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448174/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5549180/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1521694219300233

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4518755/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4080593/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27535244 https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/46/3/163

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1466853X19300409

- https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/19/1187#ref-17

- https://www.jsams.org/article/S14402440(14)00223-0/abstract

- http://www.ismni.org/jmni/pdf/77/jmni_19_300.pdf

- https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/49/19/1277 https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/4/209

.png)