What is femoroacetabular impingement?

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) syndrome is a painful hip condition that is sometimes known as “hip impingement”. It can develop when the hip is commonly placed in positions that can injure the structures deep inside the joint itself.

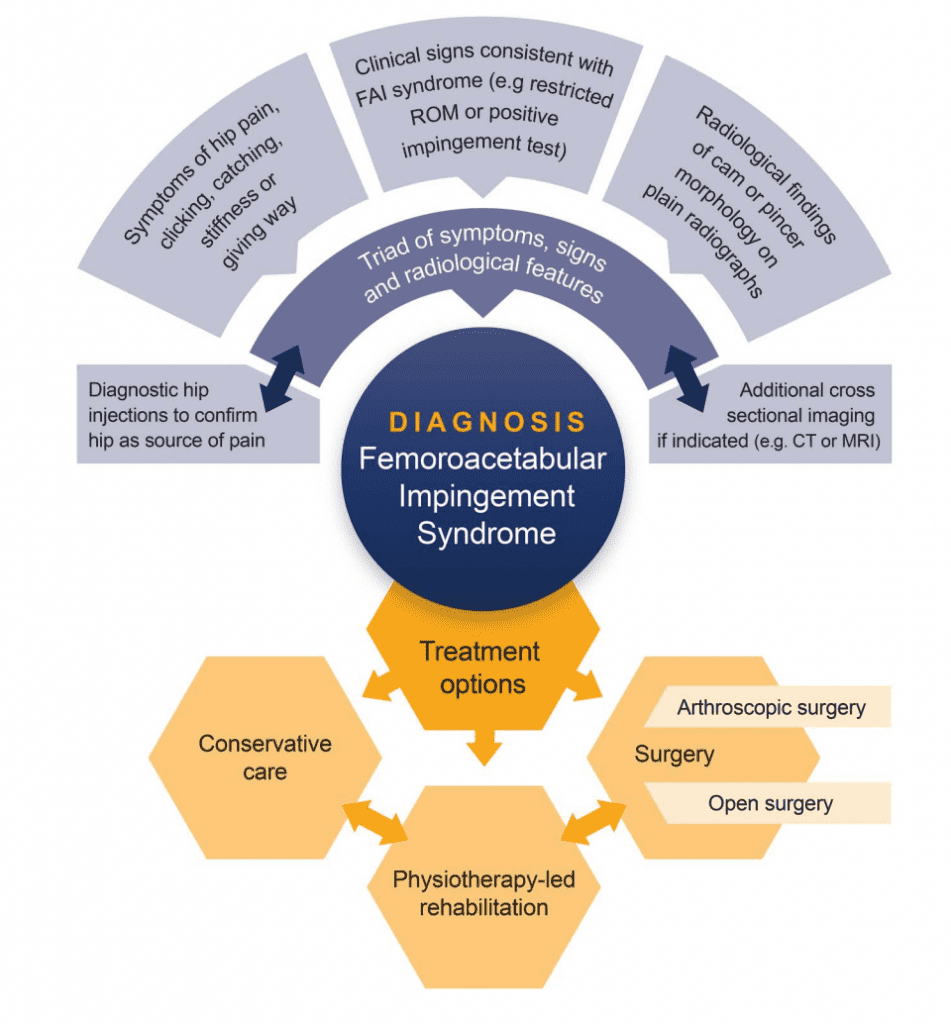

How is FAI diagnosed?

There is no gold standard test to diagnose hip impingement. A person must be symptomatic and have changes in the bone structure of the hip for it to be considered FAI.

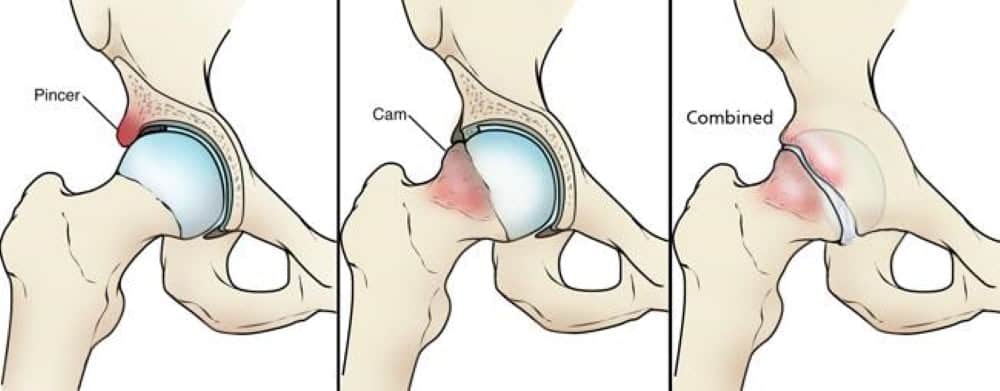

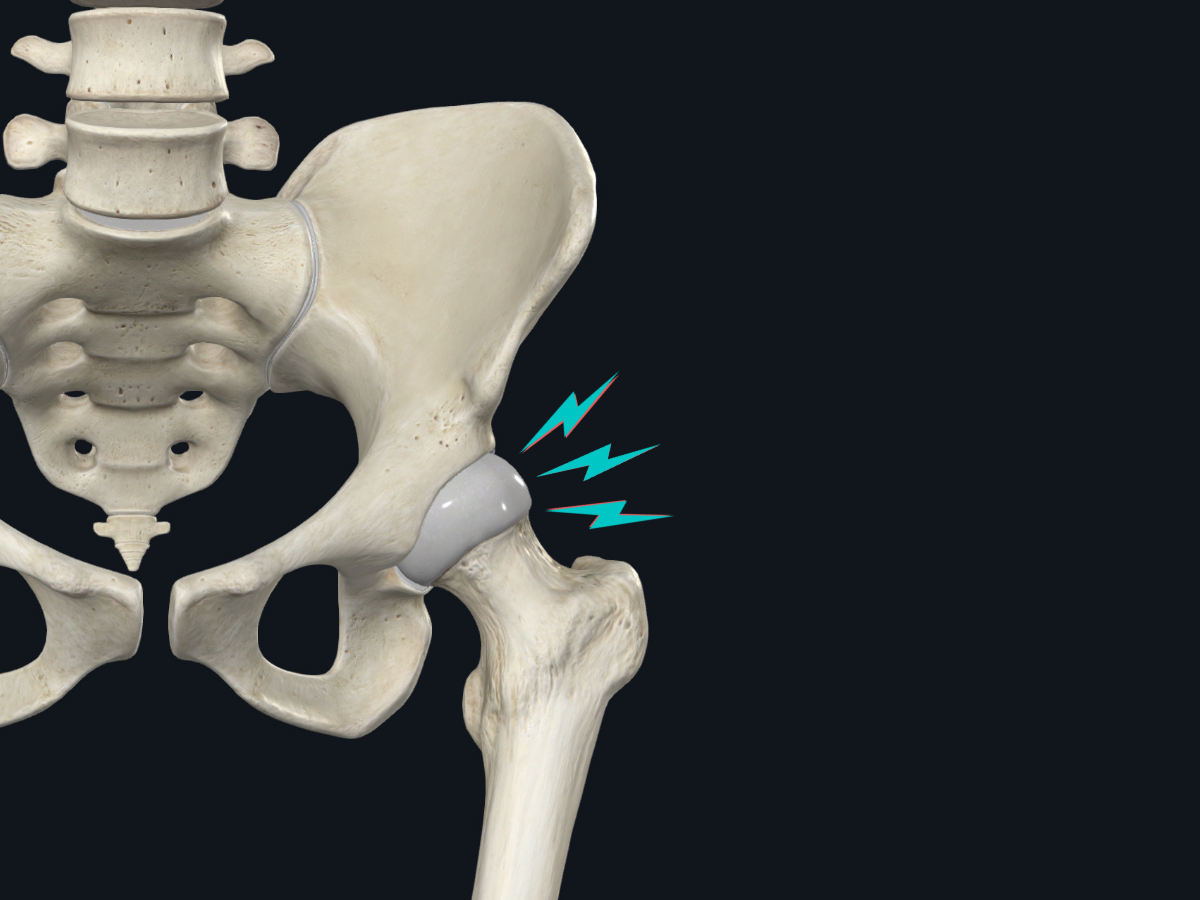

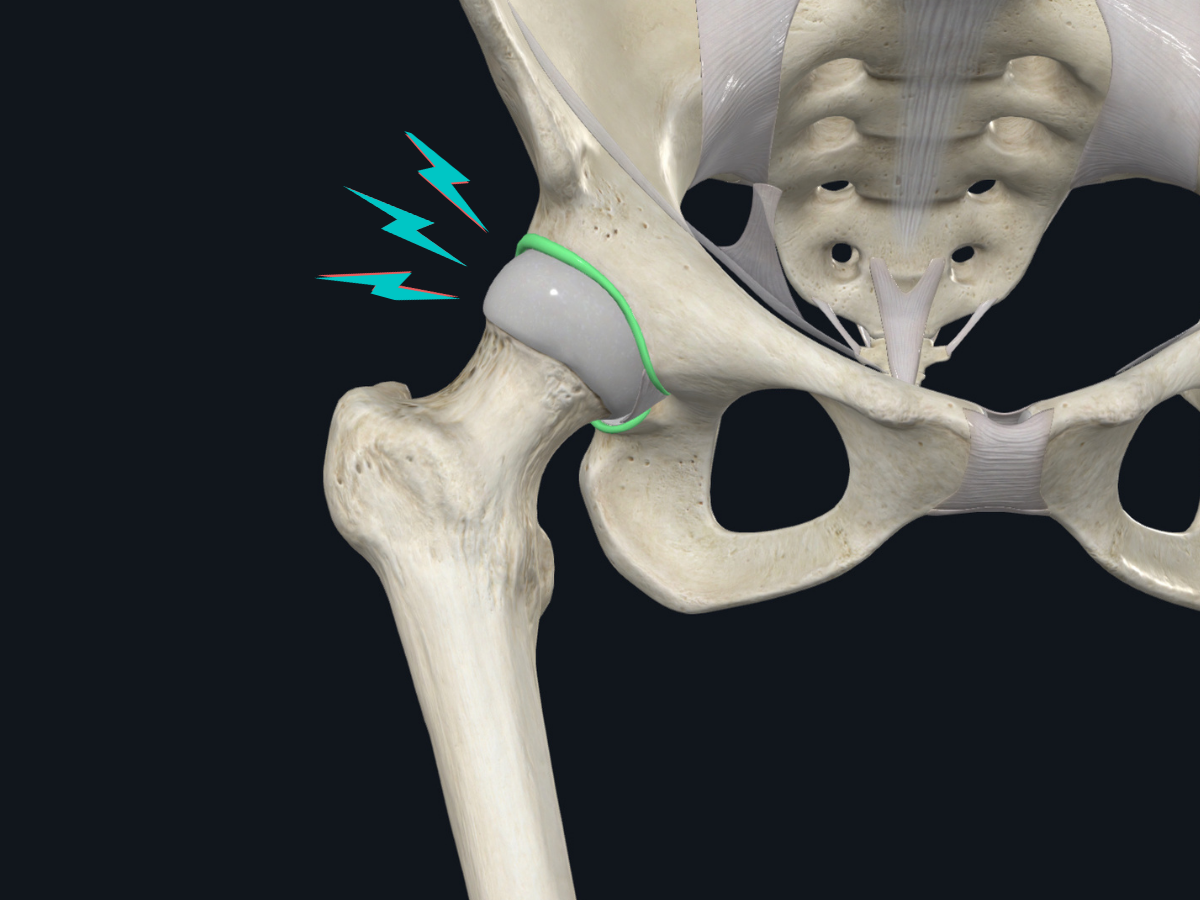

The hip is a ball and socket joint. In a normal hip, the head of the femur (i.e. the ball) moves smoothly within the acetabulum (i.e the socket). With FAI, either the ball or the socket can develop additional bony growth.

Cam

In a cam impingement, the femur can develop a bump of bone near the ball socket. This bone can butt against the socket with movements like hip flexion. The amount of bone growth can be measured on x-ray, with a higher alpha angle suggesting a higher risk of developing osteoarthritis.

Pincer

This type of impingement occurs when extra bone grows around the edge of the acetabulum (i.e. the socket).

How common is hip impingement?

Many people live with bony changes in their hips. The main difference is the presence of pain or other symptoms. In fact, athletes have a 65% prevalence of cam impingement (22% for non-athletes) regardless of symptoms. About 95% of people with a cam lesion have changes in other structures of their hip, including the labrum and cartilage, both of which are important for joint health.

Individuals with FAI can expect better outcomes and quality of life if they have greater hip flexion mobility and higher hip adduction strength.

How does hip impingement develop?

Bone changes at the hip, such as a cam impingement, typically develop at 13-15 years old and continue to change until the bone stops growing. During this period, the hip is vulnerable to the loads placed on it. Repetitive hip impingement, usually in positions of flexion, internal rotation and adduction, can lead to FAI. Genetics also play a role in this condition.

In pincer-related hip impingement, the development of FAI is thought to be due to repetitive flexion and external rotation. The acetabulum may be retroverted or deeper than normal, predisposing an individual to this type of impingement.

What are the common signs and symptoms of femoroacetabular impingement?

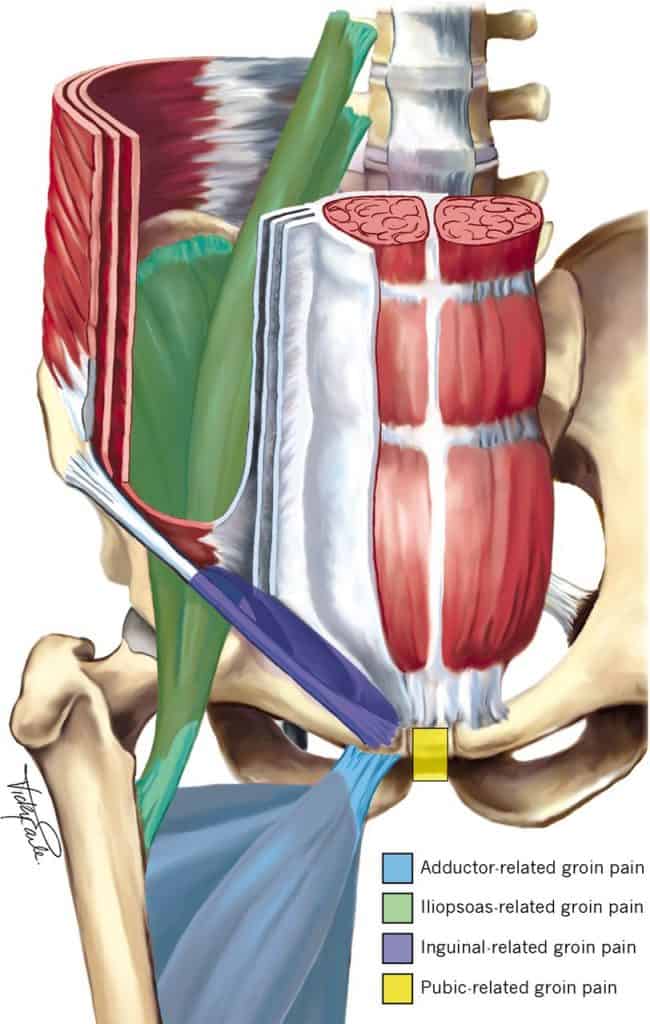

Nearly all people with hip impingement experience pain at the front of their hip and groin pain. If you are experiencing groin pain without a specific injury, there is a high likelihood that the hip is involved.

Other signs include reduced hip and trunk muscle strength, poor dynamic single leg balance, pain with positions of hip impingement (i.e. prolonged sitting), and alterations in gait such as walking with a limp. At Kinetic Labs, we use specialized equipment to measure and track these factors.

Interestingly, there may or may not be limitations in hip joint range of motion.

Why is it important to have your hip joint assessed?

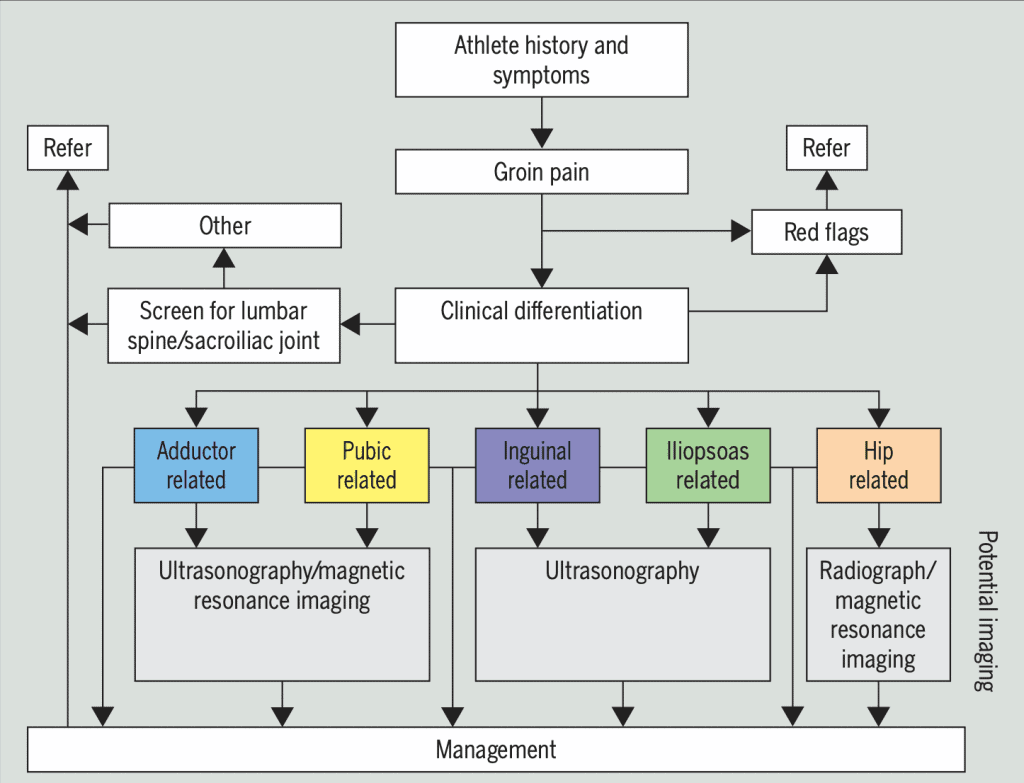

The role of a healthcare professional, such as a physiotherapist or chiropractor, is to determine the likely source of your hip pain.

In the initial clinical exam, your therapist will take a thorough history, and consider a variety of factors including:

- Age (FAI is more common in younger individuals. As you age, the hip joint can develop osteoarthritis)

- Sport/activity (there is a higher incidence of hip impingement with kicking or twisting sports)

- Injury history (previous hip pain is linked to future hip)

- Family history (genetics play a role)

- Hip symptoms (clicking, catching, locking, giving way or pain with twisting)

It’s important that more serious pathology is ruled out, including red flags such as:

- History of cancer (particularly prostate, breast and gynecological cancers that can metastasize to the hip)

- Alcohol consumption (linked to avascular necrosis of the hip joint)

- Corticosteroid use (increased risk of avascular necrosis and stress fractures)

Next, your therapist will use a cluster of tests to rule out the lumbar spine and SI joint as a source of your symptoms. There are signs and symptoms that can help guide this process. For example, walking with a limp or pain in the groin region has a 7 times higher likelihood of hip involvement.

How is progress measured during FAI rehab?

Specific testing is used as part of the objective examination.

Hip strength

hip strength is reduced in people with femoroacetabular impingement. Both men and women experience reduced hip extension and adduction strength, and women also experience abductor weakness. It's recommended to measure these changes at regular intervals (every 6-8 weeks)

Hip range of motion

As mentioned, hip range of motion does not seem to differ much between symptomatic and healthy individuals. For example, hip internal rotation is not a good indicator of progress as it does not appear to change between interventions. However, those with increased hip flexion report a higher quality of life. We recommend measuring hip flexion regularly at the start and end of treatment as it predicts outcome and is sensitive to change.

Trunk function and control

Trunk muscle strength and control is impaired in those with FAI, so regularly testing these regions is important. The side bridge test is a good indicator of trunk muscle strength, with a goal of above 34 seconds each side (on initial assessment and with regular testing intervals on follow-up). Next, single leg hop tests done at initial assessment, follow-up and prior to returning to sport can give better data about trunk control and single leg power. Ideally, an individual should have a hop to height ratio of above 0.37. Lastly, individuals who can perform a single leg sit to stand test of above 16 repetitions, tested prior to returning to sport, have shown better outcomes.

Is surgery helpful for hip impingement?

A few studies examined the outcomes between hip arthroscopy and physiotherapy. At 6-12 months, symptom improvement slightly favoured surgery but there was no difference at 2 years between the groups.

It’s important to consider the risks with surgery. Some preliminary evidence suggests there is higher risk of cartilage damage with hip arthroscopy, although it's unclear if these changes are permanent.

It’s a good idea to exhaust your non-surgical options first due to these risks, as well as the fact that many people do not return to optimal levels after surgery.

What can I expect during rehabilitation for hip impingement?

Exercise is the cornerstone of treatment over the course of at least 3 months. A focus on lower extremity strength, core strength and single leg control exercises is crucial. Targeting range of motion, especially hip flexion, can improve quality of life and pain scores.

The goal is to optimize loads on the hip joint. Although there is no current consensus for return to play criteria, it is best to aim for hip and trunk strength symmetry of above 90%, low to no hip pain, and an individual readiness and confidence to resume activities.

.png)