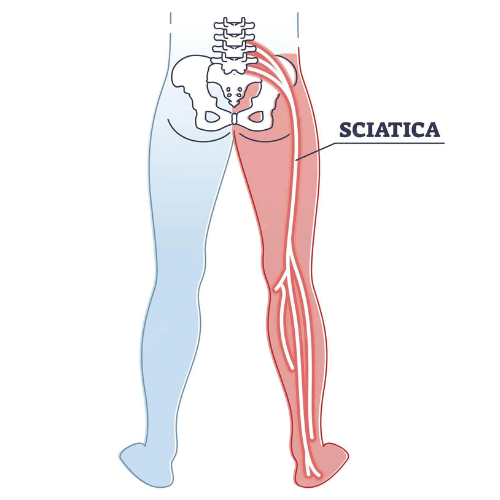

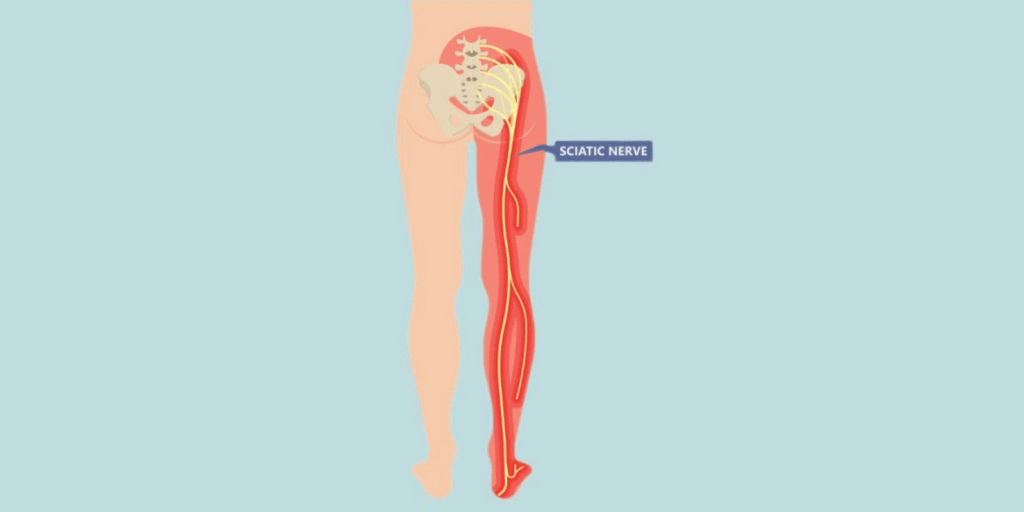

Sciatica is an umbrella term to describe nerve pain that radiates down the back of the leg. Many healthcare professionals believe that sciatica is an outdated term; it is not specific enough to guide treatment. It is very common, with 60% of individuals with back pain also presenting with leg symptoms.1

There are three main reasons why you may experience pain at the back of your leg – referred pain, radicular pain, and radiculopathy.2

Referred pain is poorly localized pain from muscles, joints, ligaments or other structures except nerves. This pain is felt at a different site to where the original injury occurred. For example, you can have visceral pain, which is pain from a body organ (from your liver, etc) that is felt in a different area – such as your shoulder.

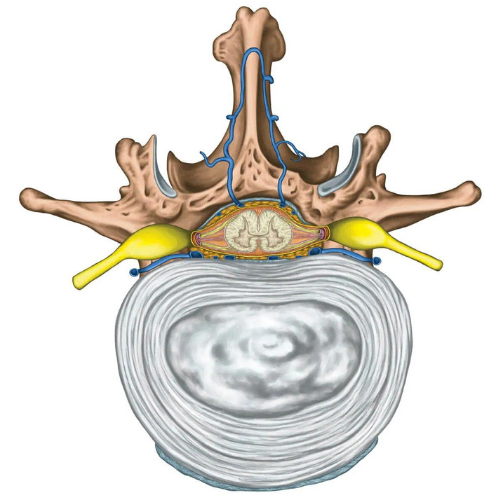

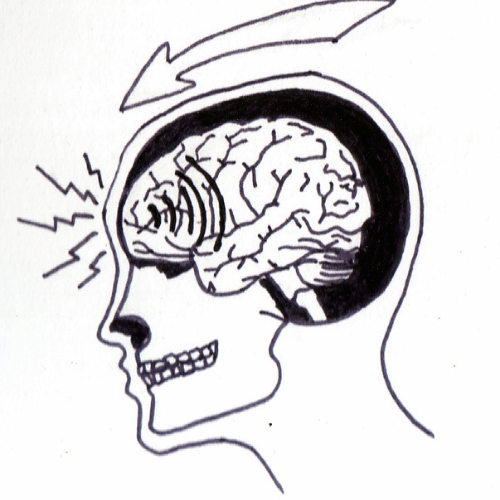

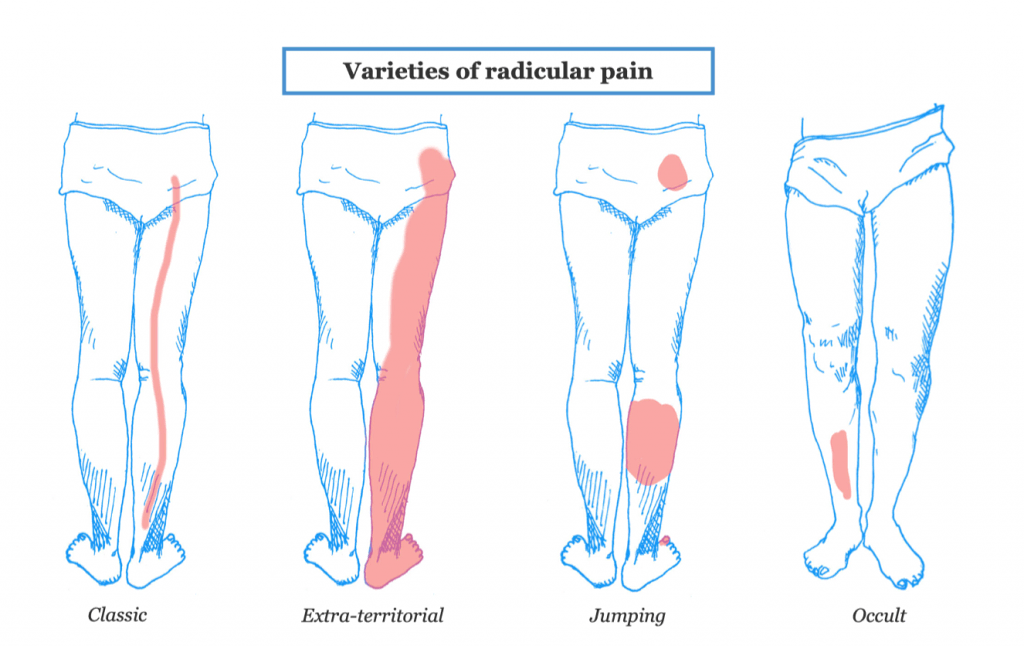

Radicular pain is a sharp, shooting, or “bright” feeling sensation that typically follows a specific pattern. Normally, nerves send a signal from the periphery (i.e. from the receptors in your skin or joints) to your spinal cord and brain. In radicular pain, this signal gets activated at the nerve root, near the spine, instead of the periphery.

Lastly, radiculopathy describes a loss of function from an injury to the nerve root. In fact, pain is not part of the criteria to diagnose radiculopathy.

In reality, many of these specific conditions co-exist. For example, it’s not uncommon to have a painful radiculopathy or radicular pain with referred pain. Perhaps this is why sciatica as a term has persisted despite its shortcomings.

Nerves are injured in two main ways – mechanical pressure and chemical irritation.

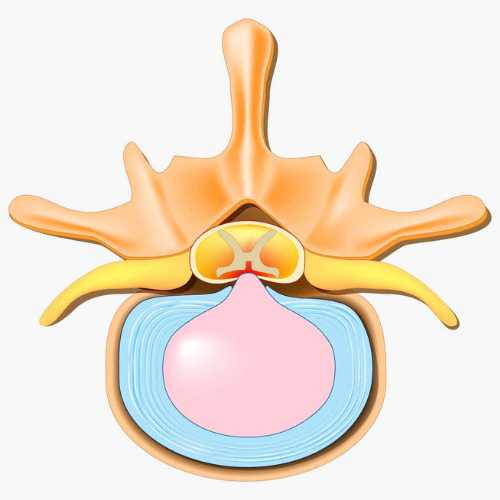

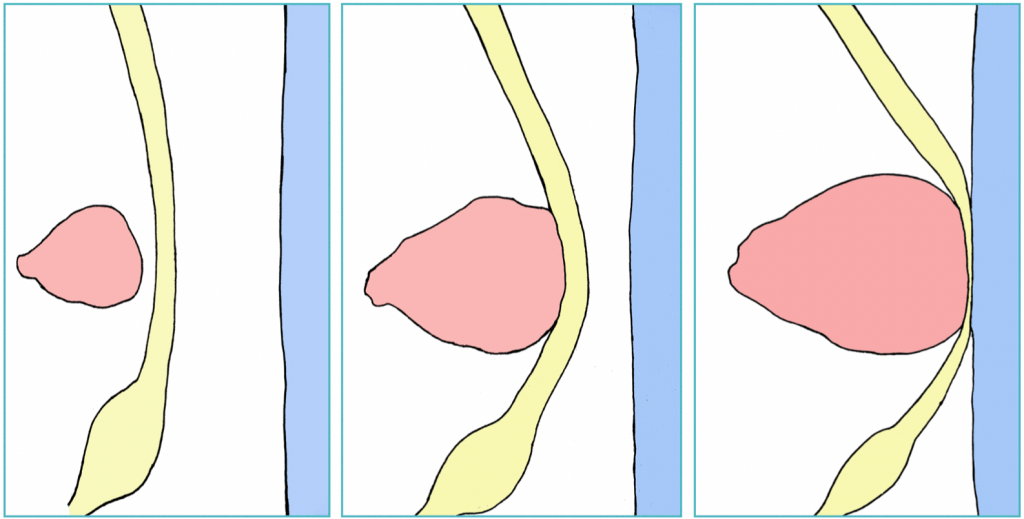

Mechanical pressure can be broken down into three categories – crowding out, bowstringing and compression.2 Most people have the visual of a bulging disc compressing a nerve against another structure as the cause of sciatica. While this type of severe compression can happen, it is not as common. A nerve can be stretched and thinned, causing a bowstringing effect and compromising nerve function. Nerves pass through areas in the body that have many other structures nearby. These other structures can crowd-out a nerve, displacing it and injuring it from the increased pressure.

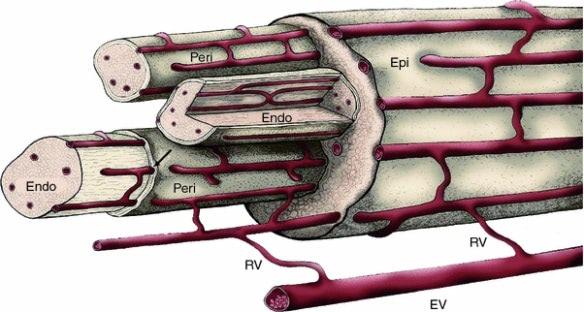

Nerve injury from chemical irritation is often overlooked. The body does a good job of keeping structures separate so that inflammation and irritation does not occur. When the body is injured, substances that don’t normally interact come together to cause an inflammatory response. These chemicals can irritate structures, such as the nerve root, and cause sciatica symptoms.

In most cases, symptoms can be traced back to a specific injury. But sometimes it is difficult to pinpoint the root cause. This can be for several reasons. Thinking about the mechanisms of nerve injury, some scenarios occur over long periods of time. For example, bony changes in the spine that crowd-out the nerve, or a slow and gradual bow-stringing effect from a disc herniation. These scenarios may take many months before symptoms develop and can’t be tied to a specific injury.

Nerves are sensitive structures that rely on blood flow and oxygen to properly function. When mechanical pressure is present, the blood flow may be restricted and in some cases completely blocked, leading to a loss of conduction in the case of radiculopathy, or the generation of aberrant nerve impulses that lead to pain in the case of radicular pain. This is known as ischemia.

The most well known example of this sensation is when your arm or leg “goes numb”. After sitting or lying on the limb for a long period of time without moving, the blood flow to the nerve is disrupted. The limb goes “dead” and you lose voluntary control until blood flow, and nerve conduction, is restored. In most cases, this conduction block can be reversed if it is temporary. But when this process is prolonged, the lack of oxygen to the nerve can damage it – sometimes permanently.

Chemical irritation can also cause nerve conduction problems. This happens when immune cells from the inflammatory response break down the protective layers of a nerve.

There are many risk factors for developing nerve pain and sciatica. Some of the most common include:

Sciatic nerve pain is primarily a clinical diagnosis. There are a cluster of signs and symptoms that are characteristic of the condition, but no single test can diagnose nerve pain.1

People with sciatica usually experience the following symptoms:

The best treatment will depend on the underlying condition causing the symptoms. If the pain is coming from an organ or muscle, in the case of referred pain, treatment would be directed at those structures. Similarly, addressing the underlying mechanism is important. For example, if the symptoms are caused by compression of the nerve root, then relieving that pressure becomes the target. In extreme cases, surgery may be required.

Current guidelines recommend physical activity and exercise.3 In addition, symptom management can include spinal manipulation. Spinal injections offer short term pain relief for severe symptoms compared with placebo. Other interventions like nerve medications and oral steroids can be prescribed in some cases, but the research is unclear on their efficacy and safety.

Surgery may be required in severe or emergency cases. However, decompression and laminectomy surgeries for nerve root compression have better outcomes in the short term, but similar outcomes compared with non-operative treatments at one year.

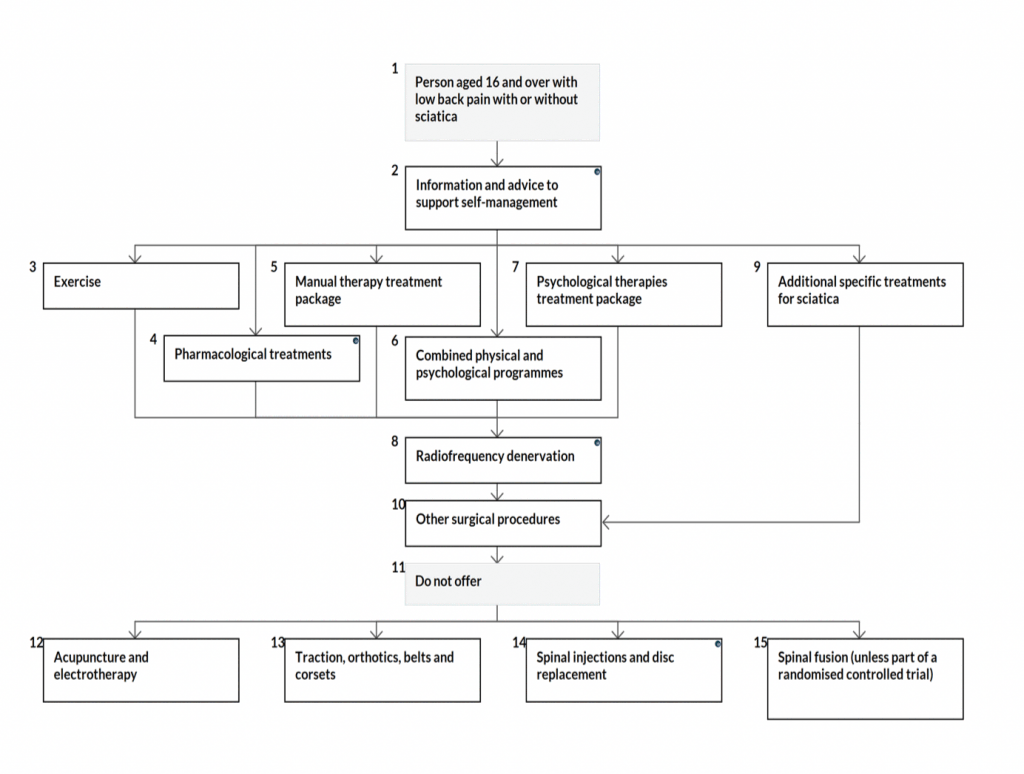

The NICE guidelines, which are evidence-based healthcare recommendations created in England, provide an updated framework for the management of sciatica.3

According to the NICE guidelines mentioned above, acupuncture is not recommended for low back pain – with or without sciatica. However, the guidelines are based on studies that include mainly traditional acupuncture. Anecdotally, electro-acupuncture (i.e. acupuncture with electrical current applied through the needles) seems to provide significant benefits for some individuals with acute nerve symptoms.

A meta-analysis of the efficacy of acupuncture in sciatica patients showed that it provided immediate pain relief in those with radiating leg symptoms.4 In our clinic, we have found that some people respond very well to electroacupuncture, while others don’t. Regardless of its effectiveness, it is only a small part of a comprehensive management plan.

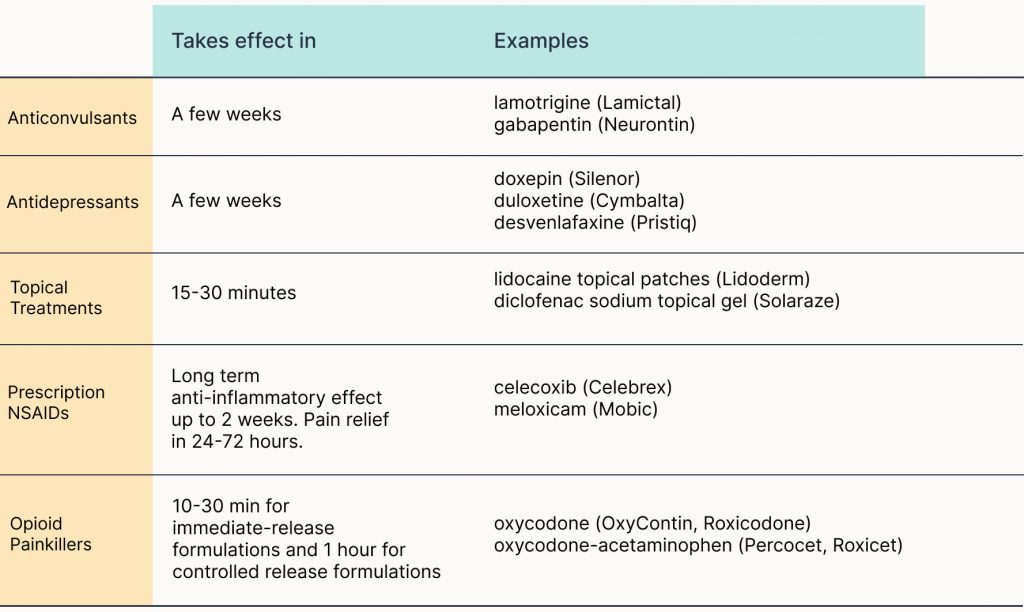

Medication is frequently used as a first line treatment for sciatica. The NICE guidelines suggest oral NSAIDs for managing low back pain and sciatic nerve symptoms. In many cases, against these evidence-based guidelines, stronger medications such as opioids, SSRI’s, gabapentinoids (pregabalin, gabapentin) and anti-epileptics are prescribed. Weak opioids are sometimes recommended if NSAIDs are contraindicated or ineffective in a specific person.

Unfortunately, research shows that many patients are routinely prescribed these stronger medications.5 These patients reported that the medications were ineffective and had significant side effects. Those who stopped taking these medications still noticed a significant reduction in their pain levels.

There is no single “best” exercise program for nerve pain. Every person and condition is unique and requires a different approach. The mechanism of your sciatica will determine which exercises to do. Some options include, neurodynamic exercises, repeated movements, and general strength and cardiovascular training.

General strengthening and cardiovascular exercises help reduce pain and increase blood flow to tissues throughout the body. Oxygenated blood can help clear out chemical irritants that may be present in the tissue. A reduction in these chemical irritants can help reduce nerve pain.

Repeated movements, such as performing repetitions of lumbar extension, can reduce leg symptoms of sciatica. The directional preference (i.e. lumbar extension versus flexion) has to be tailored to the individual depending on how their symptoms respond.

Lastly, neurodynamic exercises can be helpful to get the irritated nerve and nerve roots to calm down. Movement promotes blood flow, and increased blood flow brings in nutrients that provide symptom relief. Neurodynamic exercises stress the nerves in specific ways to maximize this effect.

Severe symptoms should subside within 6 weeks. A recent randomized control trial of 496 sciatica patients showed that the median time to symptom resolution was between 10-12 weeks. However, only 20% fully recovered in one year. This shows the variability in the recovery time.6

In another study of 452 sciatica patients in the UK, 55% reported improvement in pain and disability at one year after treatment based on recommended guidelines including physiotherapy.1

Like with most musculoskeletal conditions, the longer the pain lingers, the longer the recovery time. This is true for other nerve conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome, and sciatica is no exception.