Our shoulders are constructed to maximize our movement in many different directions. We can reach overhead, hang off of things, stand on our hands, throw or rotate our shoulders through a large range of motion. To allow for all of this movement, our shoulder joint or socket is more shallow than others, making it the most commonly dislocated joint in our body. Shoulder dislocations (where the arm bone pops out of the joint) account for approximately 50% of all joint dislocations.1 Shoulder instability can also lead to subluxations – where the bone partially comes out of the joint then goes back into place – or chronic instability.

As a former NCAA Division 1 springboard and platform diver, I’ve had the unfortunate experience of subluxing and dislocating my shoulder a few times, having a labral repair surgery, and undergoing the long rehab process to return to diving. What follows is a mix of my personal experience as an athlete, and now my professional knowledge as a physiotherapist leading athletes through this recovery process.

First, let’s discuss the anatomy of the shoulder, as it helps to understand why shoulder instability occurs, and why recovery is so complex.

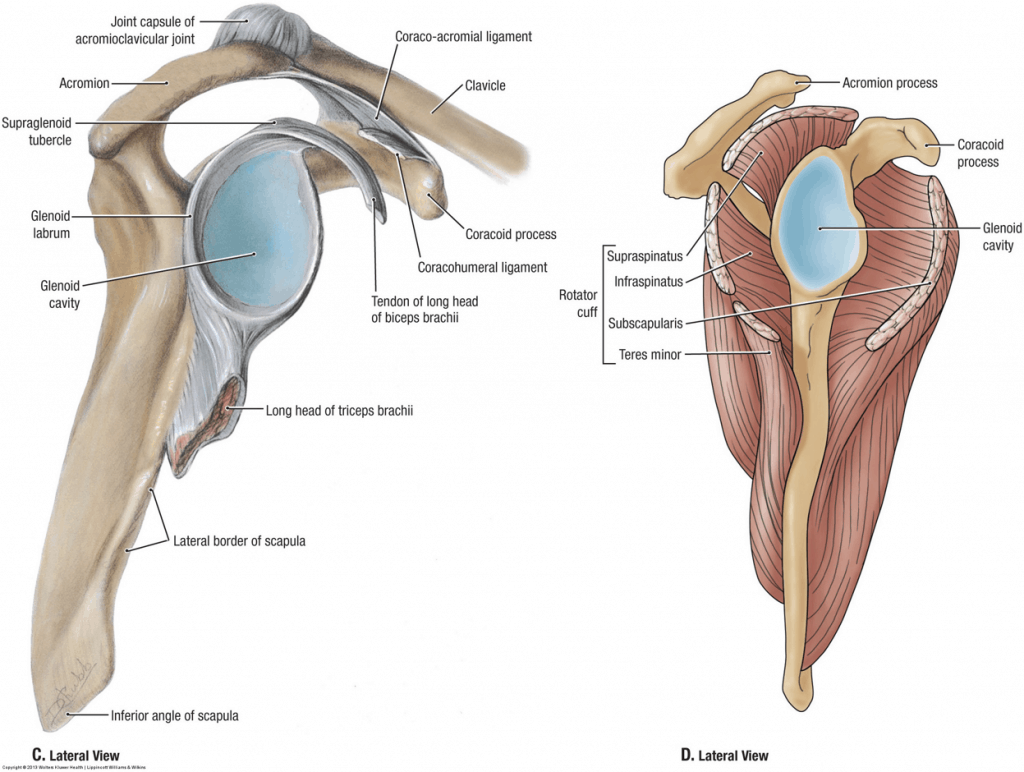

The shoulder joint consists of the humerus (upper arm bone) and scapula (shoulder blade). The humeral head is round and acts as a ‘ball’ to fit into the shallow ‘socket’ or glenoid fossa of the scapula. Together, they comprise the glenohumeral joint. Shoulder stability is the ability to keep the humeral head in the glenoid fossa.

How is shoulder stability maintained?

Many structures surround the shoulder joint to keep it stable. These include the static and dynamic stabilizers.

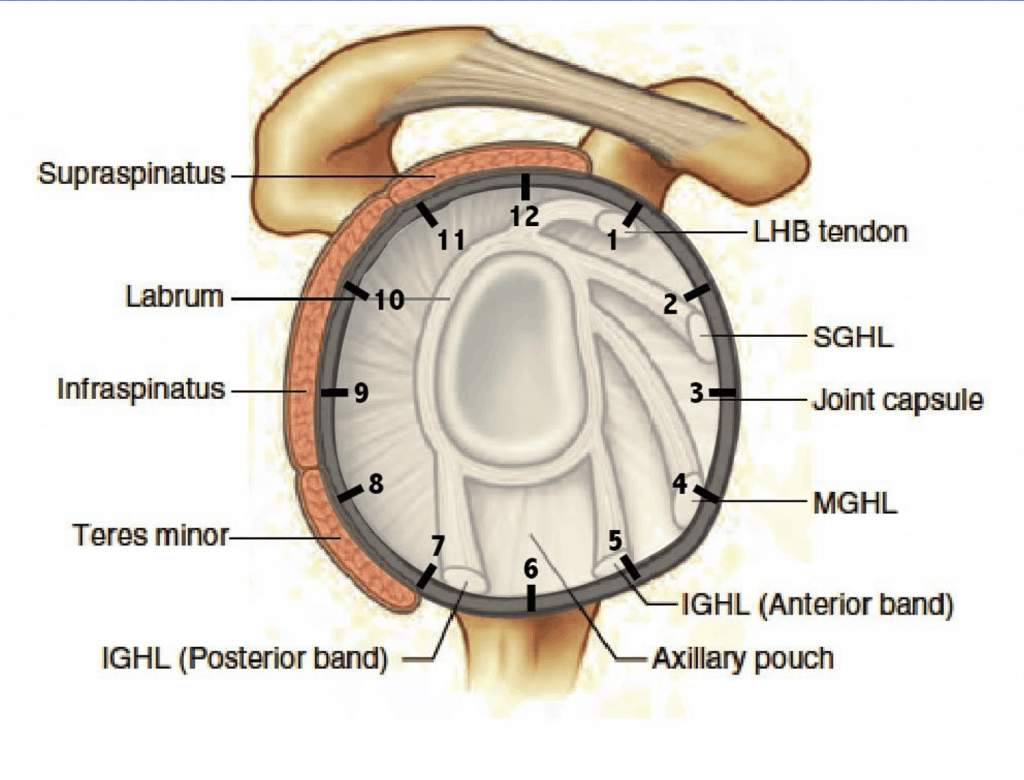

The static stabilizers make up the shoulder capsule. They include three ligaments (superior, medial, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments) and the glenoid labrum. Together they make the ‘socket’ deeper and hold the bones together firmly.

The dynamic stabilizers are the muscles around the shoulder. The muscles help to produce movement, but also keep the joint stable during movement. These include the rotator cuff muscles, long head of biceps, and deltoid. Most of these muscles begin on the humerus or scapula and have tendons that attach into the shoulder capsule.

Now this joint seems pretty simple: you have two bones that are surrounded by firm ligaments to hold it together at rest, and muscles surrounding it to help it move. But, if we zoom out and look at the surrounding area, it becomes a bit more complex.

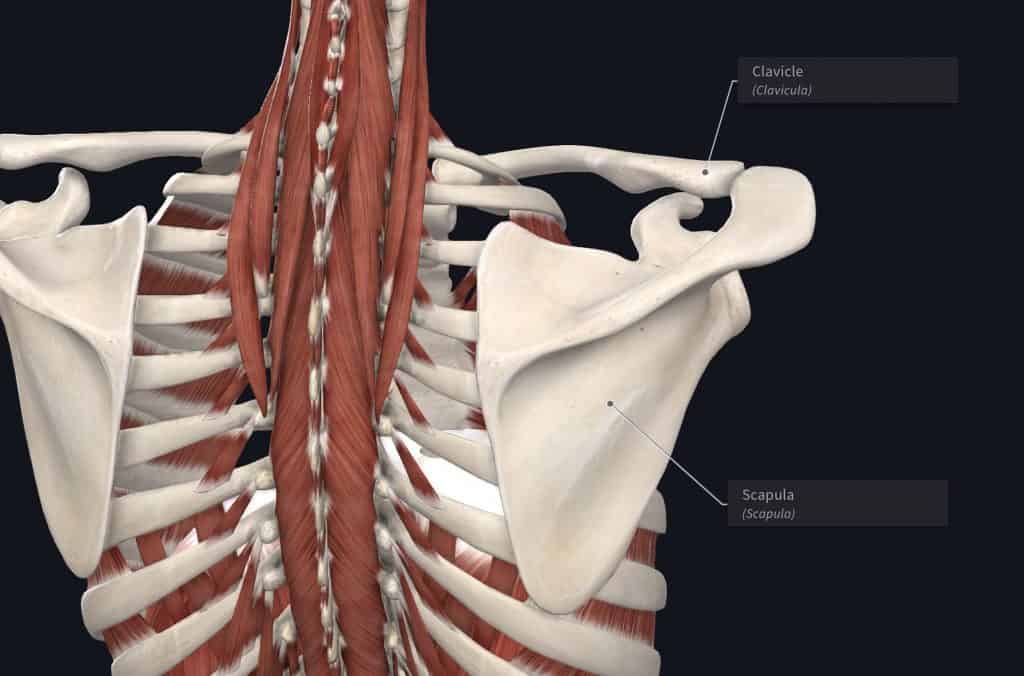

Let’s now look at the anatomy of the scapula.

The scapula, or shoulder blade, attaches to the clavicle or collarbone (called the acromioclavicular or AC joint), which then attaches to our chest. The scapula lies on our ribcage (called the scapulothoracic joint) and stays in place by the attachment of many ligaments and muscles. These scapular muscles become the secondary dynamic stabilizers for the shoulder joint.

When we raise our arm above our head, all three of these joints (glenohumeral, acromioclavicular, and scapulothoracic) must move smoothly together to create full movement. About 2/3 of movement comes from the glenohumeral joint, while the other 1/3 comes from the scapula. We call this balance of all of the muscles and joints scapulohumeral rhythm. To optimize shoulder movement and maintain shoulder stability, all of these joints, muscles, and ligaments must work smoothly together.

How does shoulder instability occur?

Traumatic injuries are those that occur due to one instance of force outside the body exerted onto the shoulder. For example, falling onto your arm, a car accident, or a bad football tackle. In my case, I was doing a handstand dive from the 10-meter platform, where my body started flipping through the air, but my fingers caught on the edge of the platform. I experienced a subluxation, and by the time I emerged from the pool, my shoulder was back in place. It was achy and sore, but I was not in much pain.

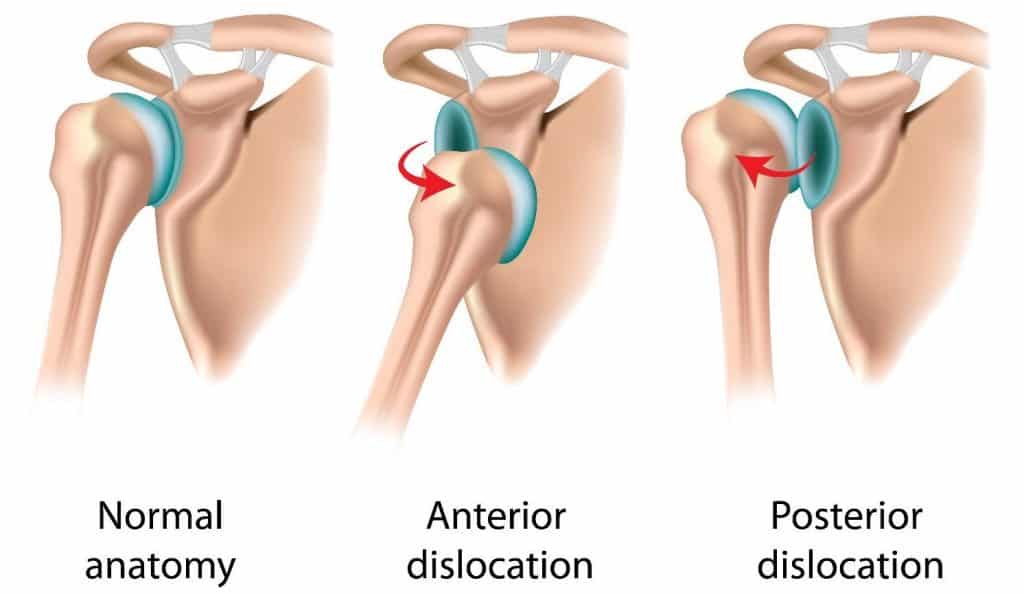

The most common mechanism for shoulder dislocations is an anterior dislocation, accounting for 95% of shoulder dislocations.2 This occurs when a posterior or backward force is applied to the arm, and the humerus comes forward out of the glenoid fossa. This usually occurs in a position of shoulder external rotation while the arm is abducted.

Non-traumatic injuries are those that occur over a longer period from repetitive stress on the area. For example, baseball pitchers, whose throwing motion uses very high velocity through an external rotation movement. It is very common for pitchers to have injuries to their labrum or joint capsule, however, this is often not associated with any dislocations or subluxations.

What happens after a traumatic dislocation?

(If you have non-traumatic instability, skip ahead to Imaging)

Chances are if you’re reading this blog and have experienced a dislocation, you’ve already been through this process. However, here is a quick summary of the initial treatment for shoulder dislocations.

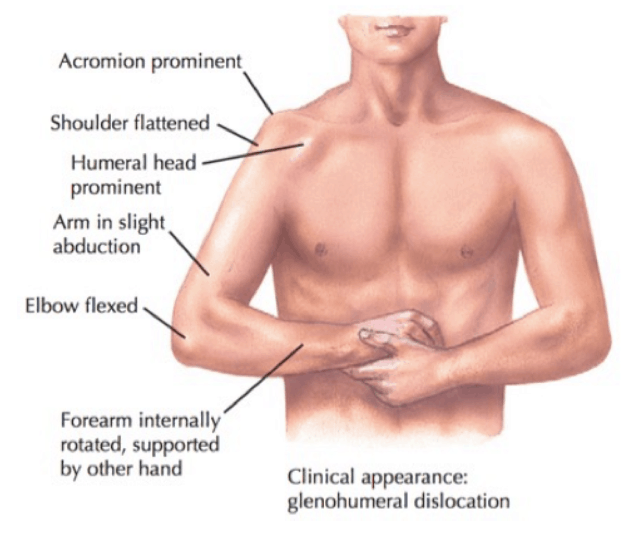

Traumatic shoulder dislocations are usually accompanied by severe pain and the inability to move your arm. Sometimes arm numbness or tingling can occur. The shoulder joint will visibly appear more square in shape, compared to the normal rounded appearance. Most people experiencing a shoulder dislocation will end up at the emergency room to have the shoulder relocated or put back into place. X-rays are sometimes taken before the shoulder is relocated to visualize what direction the dislocation is, and if there is any associated fracture. Medications including sedatives, muscle relaxants, and pain relievers can be given before relocating the shoulder. It can be very scary to think about having your shoulder relocated, but in my experience, the pain is much less after it is relocated.

Do I need an arm sling after dislocating my shoulder?

Once the shoulder is relocated, you will be placed in a sling for approximately one week. How long you are in the sling may depend on your age. Middle to older age adults may be in the sling for less time to promote early movement and prevent stiffness, while those <30 years of age at the time of first dislocation have a higher chance of recurrence so they may be in a sling for longer. Research has found that being in a sling for longer than one week does not have any impact on your chance of recurrence. As well, different arm positions in the sling have not shown any difference in outcomes.3

Am I at greater risk of a second shoulder dislocation?

Unfortunately, recurrence rates after traumatic shoulder injuries are high. Studies vary largely in percentage, with a range of 19 to 88%. Recurrence rates depend on many factors, including the initial mechanism of injury, your age at first occurrence (<20 years of age at first occurrence had a larger chance of subsequent dislocations), sex (higher occurrence in males), clinical evidence of instability, and demands of occupation and sport participation.4

Do I need imaging?

For traumatic injuries, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is sometimes indicated to better visualize the joint capsule and soft tissues around the shoulder. This will be based on the initial injury and risk factors for recurrent injury.

For non-traumatic shoulder instability, conservative treatment (physio/rehab) is recommended as the first line of treatment. If this is not successful, further imaging may be warranted to determine if surgery may be indicated. MRIs are not always conducted for those with non-traumatic injuries, as there are many individuals with labral or joint injuries who do not have any pain or symptoms, making it difficult to correlate symptoms to imaging findings.

If an MRI is required, it will typically be a specific type called a magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA). This uses an injection of contrast agent to better visualize the labrum. The labrum can also be well visualized using a 3-tesla MRI.5

What do my imaging results mean?

SLAP tear: This refers to the specific area of the labrum that is damaged – Superior Labrum from Anterior to Posterior. Picture your shoulder as a clock, with the top being 12 o’clock, and the front as 3 o’clock. SLAP tears usually occur between 10-2 o’clock. The most common labral injury in baseball players is a type II SLAP tear, where the labrum is torn from the pull of the long head of biceps on the capsule.

Bankart lesion: This is an injury to the anterior/inferior glenoid labrum (3-6 o’clock) from an anterior shoulder dislocation.

Reverse Bankart: This is from a posterior dislocation of the shoulder (the ball goes backward out of the socket). Posterior dislocations are very rare (~2-4% of all dislocations SOURCE) and usually as a result of seizures or high trauma to the area such as a car accident.

Hills-Sachs lesion: This is a depression or dent in the back of the humerus due to an anterior dislocation. When the humerus comes forward, the back of the bone can hit the edge of the glenoid fossa (socket), creating a dent in the bone.

Surgery vs. Conservative treatment?

This is the most controversial question. Research continues to compare immediate surgery, delayed surgery, or non-surgical approaches (rehab). Some favour more immediate surgery for younger active populations, while others conclude that conservative treatment can allow athletes to continue their season and potentially avoid surgery.2 Ultimately, whether or not you are a candidate for surgery will depend on your risk factors for recurrence.

Unfortunately, conservative rehab did not work for me, and after 6 months I injured my shoulder again. This time it was a full dislocation, and after an MRI showing a large labral tear, I underwent arthroscopic surgery.

What does non-surgical rehab entail?

The recovery process is very similar for both traumatic and non-traumatic shoulder instability. The main goals are to ensure full range of motion, strength, and stability through the positions that are required for daily life, occupation, and sport.

A good assessment is essential for any injury to determine your starting point. Here are the main things that we look at:

Range of motion: Usually range of motion is fairly normal. Sometimes there will be an increase in range of motion or hypermobility, while others there will be a decrease in range of motion, either due to muscles protecting the joint, or joint stiffness itself.

Strength: Strength must be tested in isolation to make sure each muscle is strong individually, as well as in groups to ensure that the muscles are working well together (the scapulothoracic rhythm that we discussed with anatomy)

Proprioception: Proprioception is the ability to determine our body position in space. This is very important for shoulder rehab, as it helps us to build awareness of the position of our shoulder joint. E.g. to spike a volleyball, you need the awareness of where to reach your arm in space to connect with the ball, then the force to hit it.

Once your starting point is determined, rehab will mostly focus on progressive exercises. Exercises will start with basic movements to build strength, then branch out to more sport-specific movements.

What is the recovery process after shoulder surgery?

Rehab after surgery will still have the same focus of regaining strength and function for sport, however, the starting point is different. After surgery and being in a sling for 2-6 weeks the arm will be very stiff and weak.6 When I had my sling removed I was unable to reach up to touch my face for a while, due to restrictions in my movement, and also lack of strength.

Rehab will begin with range of motion exercises to regain motion, and strengthening exercises of the entire shoulder and scapula to improve strength. Generally, full range of motion should be restored by 12 weeks, and sports may begin to resume at 4 months (e.g. gentle throwing), however full sport participation usually requires 6+ months of recovery/rehab.7

Would I change anything about my recovery?

This is a question I’ve asked myself a lot since becoming a physiotherapist and learning the background behind the injury. Should I have gotten surgery sooner? Was surgery even needed?

In short, I wouldn’t have changed anything. When my injury occurred I was lucky enough to have a great team of athletic therapists, physical therapists, physicians and surgeons. I trusted them fully, and still believe that they made all of the correct decisions for my care. Yes, I did about 6 months of intense rehab before dislocating my shoulder again and undergoing surgery, but I had an equal shot of rehab working and avoiding surgery altogether. To me, that time and effort was worth it.

Now as a physiotherapist, I enjoy sharing my experiences to help athletes make these decisions and guide them through their rehab process. While the process is long and at times frustrating, it’s exciting to create tailored plans that are unique to each person and the demands of their sport.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459125/

- https://online.boneandjoint.org.uk/doi/full/10.1302/2058-5241.2.160018

- https://meridian.allenpress.com/jat/article/50/5/550/112702/Management-of-Primary-Anterior-Shoulder

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749806316303279

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29582141/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12925631/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12403201/

.png)