Humans are built to be able to run long distances because it helped us survive in the past when we had to hunt and gather our food. Although we don't have to do that anymore, some people still like to run long distances because it's good for their health. But running long distances can also lead to injuries, especially in the bones.

What is a stress fracture?

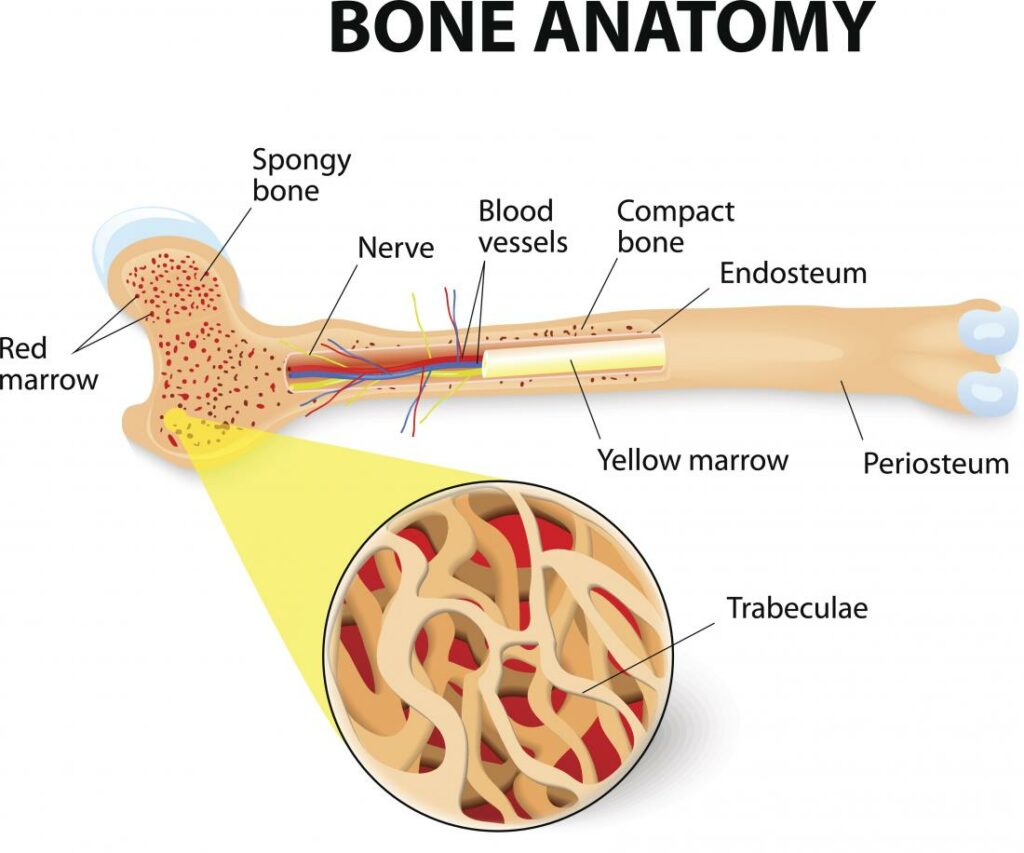

The structure of bone is made up of cells that are held together by a protein matrix. The cells are called osteocytes and they are connected to each other by proteins called collagen. When a bone is placed under stress, the osteocytes produce more collagen to make the bone stronger. However, if the bone is placed under too much stress, the osteocytes can't produce enough collagen to keep the bone from breaking. This is called a stress fracture.

A stress fracture is a small crack (microdamage) in the bone that can occur from overuse or repetitive stress. The crack may not be visible on an x-ray initially and may only show up as a small area of increased density. If the stress fracture is left untreated, it can progress to a complete break in the bone.

Microdamage is tiny bits of damage that happen to bones when they are put under stress. The amount of microdamage that happens to a bone is related to how often, how hard, and how fast the bone is stressed. Once microdamage happens, the bone starts a process of targeted remodeling to fix the damage. This process involves breaking down the damaged area and then building up new bone to replace it. This happens until the bone is back to its original strength.

How do stress fractures occur?

The pathophysiology of a bone stress injury (BSI) is not fully understood, but it is thought to involve an imbalance between load-induced microdamage formation and its removal. This means that when bones are exposed to forces during running, they may sustain small amounts of damage. If this damage accumulates faster than the body can repair it, it can lead to BSI.

How common are stress fractures?

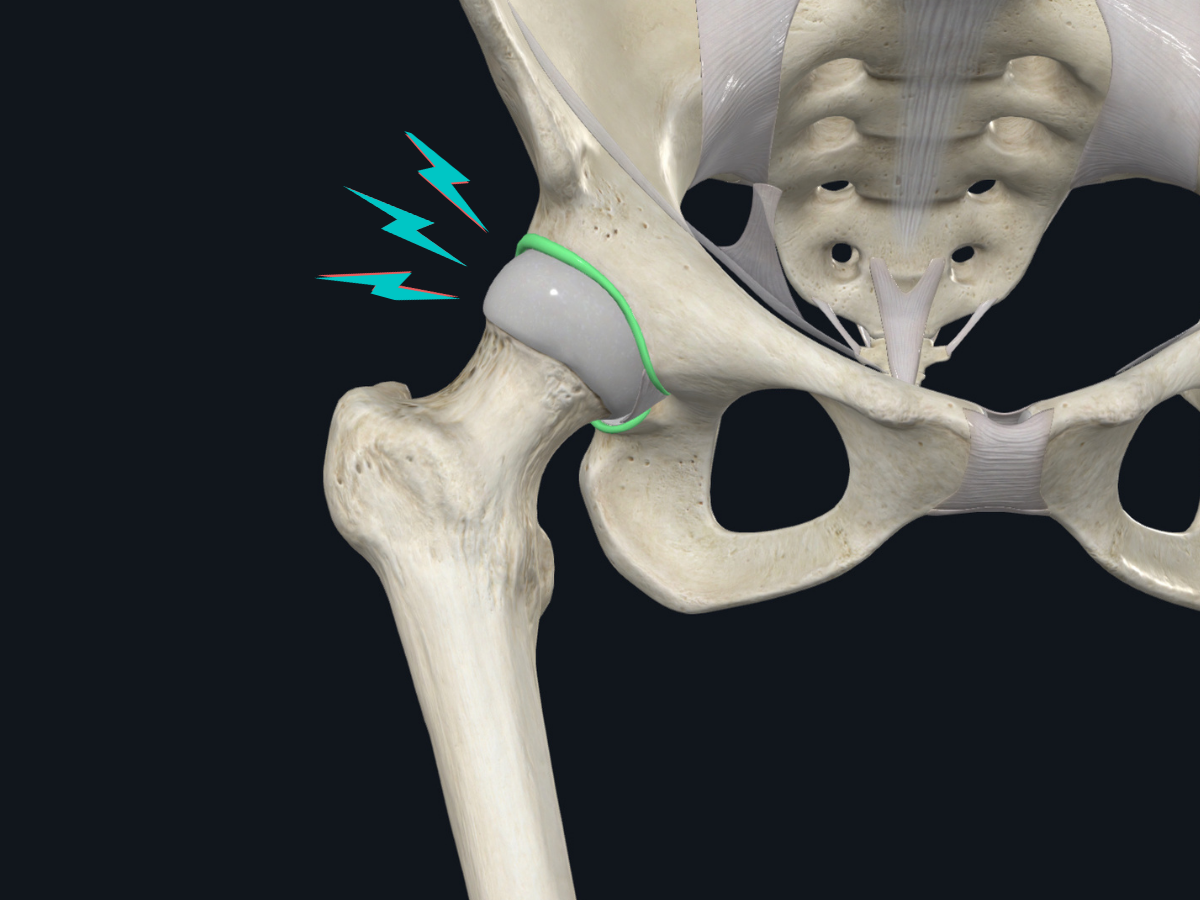

Stress fractures are frequently seen in long-distance runners. Between one third and two thirds of competitive runners have a history of BSI, and the recurrence rate is high, with 10.3% to 12.6% of runners who have had BSI sustaining a subsequent BSI when followed for 1 to 2 years. BSI typically occurs in the tibial diaphysis (the long, narrow middle section of the tibia, or shinbone), with the majority of other BSIs occurring in the femur, fibula, calcaneus, metatarsals, and tarsals, but can occur in any bone region.

What are the symptoms of a stress fracture?

BSIs (bone stress injuries) often present with a history of activity-related pain that gradually gets worse over time. The pain is usually described as a diffuse ache that occurs after a certain amount of running, and it does not improve as the person keeps running. As the injury progresses, the pain may become more severe, localized, and occur at an earlier stage. Eventually, the pain may result in the person being unable to run. On physical examination, the most obvious feature of a BSI is localized bony tenderness. Imaging, such as an MRI, is usually needed to confirm the diagnosis.

What are the most common areas to develop a stress fracture?

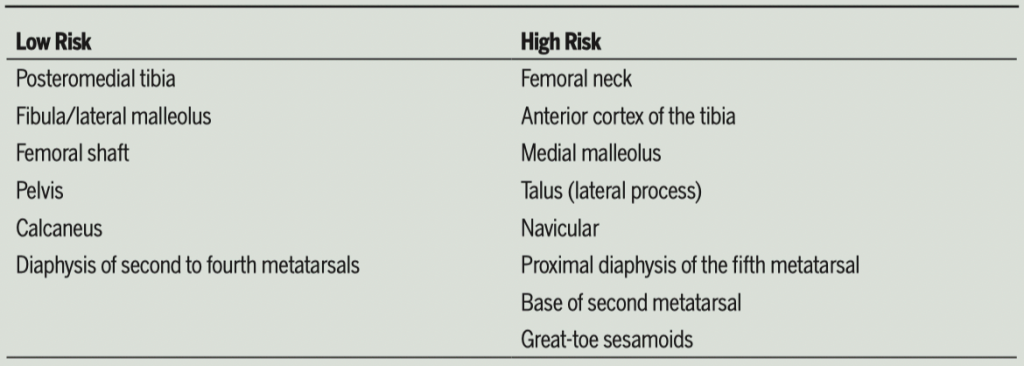

Most bone stress injuries are low risk, meaning they heal without any special treatment. But some stress fractures, especially those in certain places, can be hard to diagnose and manage. These high-risk BSIs may need special treatment, like not putting weight on the injured bone for a long time, or having surgery. Factors that determine the best management choice for a high-risk BSI include where the injury is, how long the person has had symptoms, and whether there is a cortical defect (a problem with the bone).

What are the risk factors for a stress fracture?

It is very difficult to study how runners get bone stress injuries because it requires following a lot of people over a long time. Some scientists have tried to study it by looking at runners who have already gotten the injury and comparing them to people who have not, but this isn't a perfect way to study it either. However, there are two things that affect how much strain is too much: how much the bone is pushed or pulled, and how strong the bone is.

During running, the load applied to a bone represents the summation of external and internal forces. The components of these forces are magnitude, rate, frequency, duration, and direction. These components influence, respectively, the magnitude, rate, frequency, duration, and location of bone strain. Scientists are working on ways to precisely measure the total load being applied to a bone, although it is not currently possible. In the meantime, they have been using surrogate measures, including measuring bone strains, bone acceleration, and ground reaction forces.

Do biomechanics matter for the development of a stress fracture?

The biomechanics of a person's movement can contribute to their risk of developing a bone stress injury. This can be due to abnormal forces on the bones, or to abnormal movement patterns. Runners who have had a bone stress injury in the past tend to have higher rates of acceleration and vertical ground force loading than people who have not had a bone stress injury.

Torsional loads have also been associated with bone stress injury history. Abnormal movement patterns can also increase the risk of bone stress injury. For example, high-arched individuals exhibited reduced joint excursions and higher stiffness, and had a greater history of bone stress injury. Other static variables reported to be related to bone stress injury include increased external rotation range of motion of the hip, leg-length discrepancy, pes planus, and pes cavus.

Do training loads influence the risk of stress fractures?

Chronic introduction of high absolute load magnitudes, rates, and accelerations (like when running long distances) may lead to bone fatigue, particularly when the number of loading cycles is high. Bone fatigue is the weakening of bones due to repetitive stress or impact. However, the influence of these variables may be most prominent when runners attempt to progress their training. So if you want to avoid getting a bone injury from running, you should slowly increase your speed and the distance you run, rather than doing it all at once. Large changes in how much you run can lead to too much microdamage forming in your bones, which can lead to a stress fracture.

Is muscle strength protective against bone stress injuries?

Training changes might make someone more likely to get a bone injury, but the risk might be increased if the person has weak muscles. Muscles help protect bones from impact by absorbing some of the force, and when they are weak they can't do this as well. Fatigue also makes bones more likely to break. Some studies also found that people who are more likely to get a bone stress injury have smaller and weaker muscles.

Does the type of running surface matter for a stress fracture?

External factors such as the surface you run on can affect your risk of bone stress injury. Running on harder surfaces (like asphalt) has been hypothesized to increase the amount of force on your bones compared to softer surfaces (like grass or sand). However, it is not clear if this increased force on bones from running on harder surfaces actually causes more injuries. Some studies have failed to find a connection between running injuries and the type of surface runners train on after controlling for other factors (like how far they run each week). It may be that what is important is whether a runner has recently changed the type of surface they are running on. For example, if a runner usually runs on a treadmill but starts running outside on asphalt, this change in surface may increase the risk of bone stress injury.

Does the type of footwear or shoe influence stress fracture formation?

Shoes and inserts can help protect your bones from injury. They act as filters, reducing the impact of ground forces. They also can influence motion of the foot and ankle, and the way forces are transmitted up the kinetic chain. Some studies have shown that shoes and inserts can help reduce the risk of bone injuries during military training. It's not clear yet if they offer the same benefit to runners. Some people even think that running barefoot may help prevent injuries.

Does baseline bone health protect against stress fractures?

The amount and rate of strain on a bone depend on how much load is applied to it and how well the bone can resist being deformed. Bones that are less rigid (not as strong) experience more strain and are more likely to be damaged than bones that are more rigid. Factors that make a bone less rigid include having less mass (weight) and having an irregular structure. Three things that can make a bone less massive and less strong are not exercising, not having enough energy, and not getting enough calcium and vitamin D.

Are more active people less likely to develop a stress fracture?

If you're physically active, it means your skeleton is better able to resist being bent or broken. This is because your skeleton responds to the mechanical loading (or forces) of your physical activity by depositing a small amount of new bone on the outer surface. This makes the bone stronger and less likely to break.

Are females more at risk for bone stress fractures?

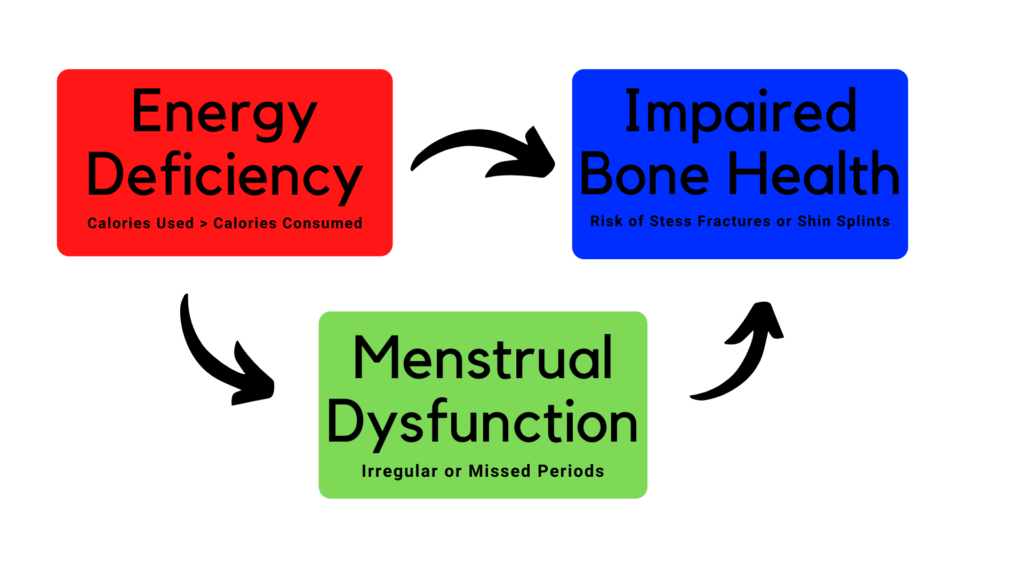

Female athletes are more susceptible to bone stress injuries than male athletes. This is because of the female athlete triad, which is when energy availability, menstrual function, and bone mass are interrelated. Low energy availability happens when someone doesn't have enough food to meet their exercise energy expenditure, and this impairs the ability of bone to repair microdamage.

Can imaging (X-ray, MRI, etc) detect a stress fracture?

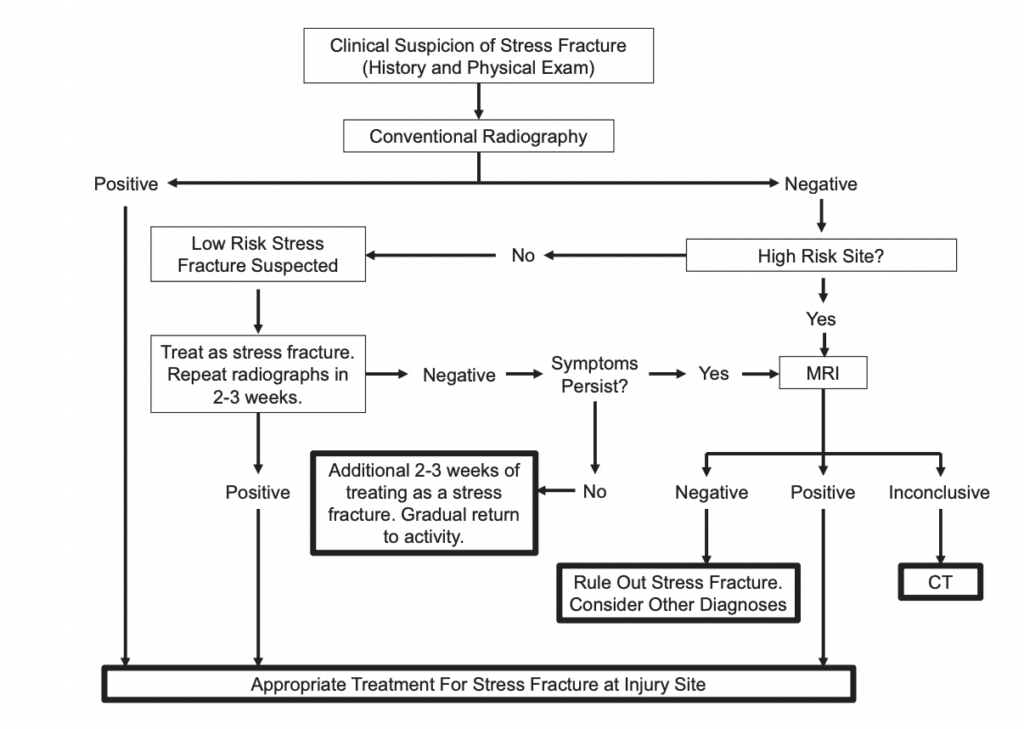

A systematic review looked at different ways of using imaging to diagnose lower extremity stress fractures and to recommend the best way based on the available evidence. The best way to diagnose stress fractures according to this review is through MRI, which is more accurate than other methods, including x-rays, and does not involve exposure to ionizing radiation. CT is not as good as MRI, but it is better than x-rays. Bone scan are useful for excluding a stress fracture but not for diagnosing one. Below is a treatment algorithm that was suggested by the researchers.

What is the treatment for a stress fracture?

The good news is that, for the most part, BSIs are not very serious and will heal without complication. The treatment for a BSI usually involves two phases: (1) modified activity (i.e., no running for a while) followed by (2) a gradual resumption of running. The goal is to get the runner back to his or her pre-injury level of function as quickly as possible without compromising the healing process. However, it is worth noting that BSIs have a high recurrence rate. This means that, once a runner has had a BSI, he or she is more likely to have another one in the future. Therefore, it is important for runners who have had a BSI to take steps to reduce the risk of future BSIs.

Phase 1

There is a question of whether or not athletes should temporarily discontinue running and do other activities when they have low-risk BSIs. The answer to this question is that it depends on the individual situation. Usually, the athlete will need to do some modified activity, and the amount of time spent doing this will be based on how much pain the athlete is in. If the athlete is in pain during or after an activity, it means that the area where the BSI is healing is being overloaded, and the activity needs to be changed. The goal for the athlete is to be pain-free during activities of daily living. To help with this, different types of shoes may be worn, depending on where the BSI is located. If the athlete cannot walk without pain, they may need to use assistive devices or a pneumatic leg brace. In some cases, the athlete may need to be non-weight bearing for a short period of time.

The initial period after being diagnosed with a bone stress injury is a good time to start addressing possible contributing factors. A detailed running and physical activity history is important. Consider not only recent changes in running frequency, duration, and intensity, but also participation in any new physical activities beyond running. Bone stress injury risk reflects the sum of all bone loading, and loading from non-running activities may be enough to push an athlete beyond his or her injury threshold. Also take note of any recent changes in running surfaces, shoes/inserts, or technique. By combining knowledge of recent running progressions with knowledge of lifelong physical activity history, it may be possible to provide a runner returning from a bone stress injury with advice regarding future running-program design. For instance, novice runners with a minimal physical activity history may need to progress their training program at a slower rate to avoid overloading the skeleton and disrupting the homeostasis between microdamage formation and removal.

Maintaining your conditioning is important for a seamless return to running after a bone stress injury (BSI). You can do this by introducing activities early on that will help maintain your cardiovascular performance. Some examples of activities that can help with this are cycling, swimming, deep-water running, and antigravity treadmill training.

Some methods that have been proposed to help heal a BSI faster include low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, and electromagnetic and capacitive coupled electric fields. However, there is not yet enough evidence to say for sure if any of these methods actually work. There are also some drugs that may help with healing, but they are not yet approved for this use.

Phase 2

In this phase, a progressive return to running is started. Graduated running programs are used in the management of low-risk BSIs to introduce controlled loading and facilitate a return to running in a timely yet safe manner. While loading (exercise) is central to the development of low-risk BSIs, recovery is best met by a balance between rest from aggravating activities and performance of appropriate loading. Appropriate loading can be defined as loading that does not provoke BSI symptoms either during or after completion of an activity. Once a runner with a low-risk BSI becomes pain free during unassisted walking, the runner can start the gradual process of reintroducing running-related loads. While there is no established protocol for returning to running during recovery from a low-risk BSI, various programs have been developed based on clinical experience.

If someone is trying to heal from a bone injury, it's important to be careful about how much they change their running program. They should only change it by a little bit each week, and it's helpful to keep track of their progress in a diary. It's also a good idea to take some breaks from running and do other, lower-impact activities.

References

- Management and Prevention of Bone Stress Injuries in Long-Distance Runners. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. Published Online:September 30, 2014 Volume44 Issue10 Pages 749-765. https://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.2014.5334

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Various Imaging Modalities for Suspected Lower Extremity Stress Fractures: A Systematic Review With Evidence-Based Recommendations for Clinical Practice. Alexis A. Wright, Eric J. Hegedus, Leon Lenchik, Karin J. Kuhn, Laura Santiago and James M. Smoliga Am J Sports Med published online March 24, 2015 DOI: 10.1177/0363546515574066

.png)