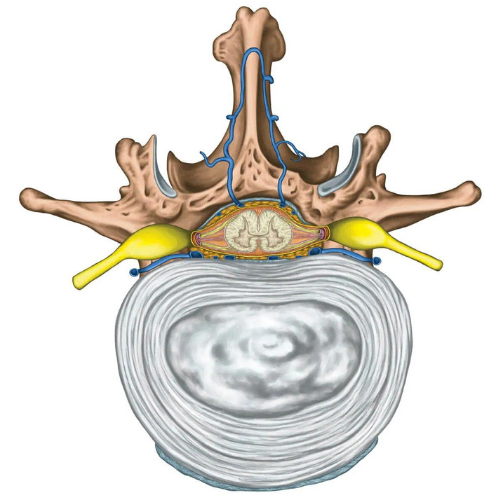

A herniated disc is one of the most common spinal injuries and involves damage to the intervertebral disc, which is connective tissue found between vertebrae in your spine. Herniated discs are often referred to as disc bulges or informally (and inaccurately!) referred to as slipped discs. It is important to address this term as discs cannot physically slip, they are firmly anchored to the vertebrae by exquisitely strong connective tissue. The disc allows for slight movement while acting as a ligament to hold the vertebrae together and plays a key role as a shock absorber for your spine. Each disc has two parts:

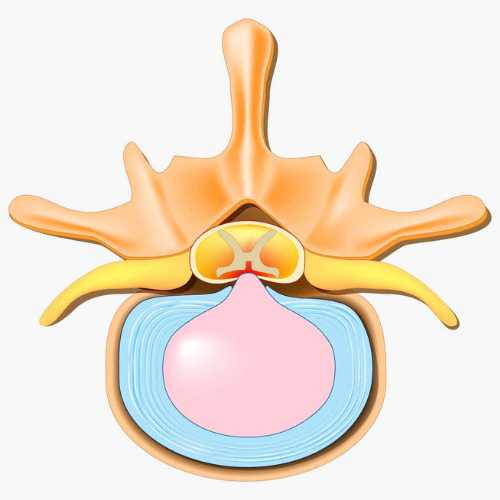

Disc herniation occurs when a tear in the firm outer ring of the disc allows the inner core to bulge out beyond the outer ring and is a common cause of back pain1. However, there are many instances of disc herniations occurring without pain and being found on MRIs in people without any symptoms2. People who experience back pain associated with a herniated disc often can recall a specific incident usually involving excessive strain or shear forces to the spine.

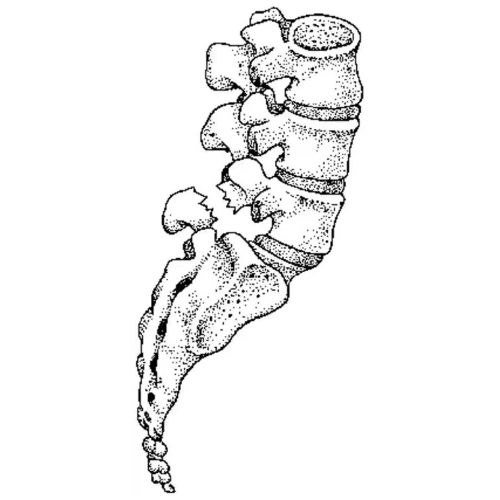

The majority of herniations occur in the lower back, the second most common area is in the lower neck, while the thoracic region only accounts for approximately 1-2% of cases4. Herniations may develop suddenly or gradually over weeks and months. Gradual herniations are the most common and are often associated with age related wear and tear of the disc, referred to as degenerative disc disease3. Cases of sudden herniation are often associated with fully flexing the spine under load, repeatedly, or for prolonged periods of time.

There are four stages of herniated discs:

Whether it is a sudden or gradual onset, herniation often occurs due to internal pressure in the disc causing the contents of the inner core to be pressed against the stretched or damaged outer ring. With sufficient pressure the inner core may bulge out. The combination of the outer ring being stretched or weakened along with increased internal pressure can result in the rupture of the outer ring which then allows the contents of the nucleus pulposus to leak out of the disc where it may press against nerves in the back and result in pain. This mechanical compression of the nerve by the disc can cause a radiculopathy and the disc material may also cause an increase in local inflammation.

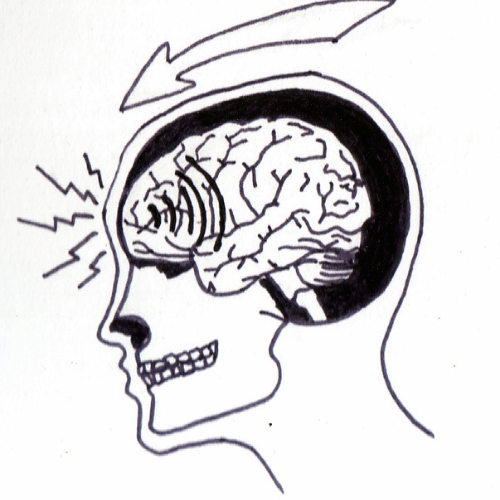

Symptoms of a herniated disc can vary depending on the location of the herniation as well as what local tissues are involved. They can range from very little to no pain, if the disc is the only tissue affected, to severe pain that radiates into the arms or legs if local soft tissue or nerve roots are involved. For those that experience pain it is often described as “burning” or “stinging” in quality.

The disc has a strong capacity to heal, previous studies have found full complete resolution of symptoms with conservative management in 96% of sequestrations, 70% of extrusions, 41% of protrusions and 13% of bulges5. With these rates of success, surgery is considered a last resort treatment in severe cases that do not respond to conservative care.

Physiotherapy plays a major role in the treatment of disc herniations. It is recommended for education, symptom management, restoration of functional deficits, and resumption of daily activities and exercise. Active exercise therapy is the preferred treatment and may involve directional preference movements (McKenzie method), flexibility, strengthening, and motor control exercises in order to improve strength and resilience of the back as well as improve confidence and stability and reduce the risk of future back injuries.