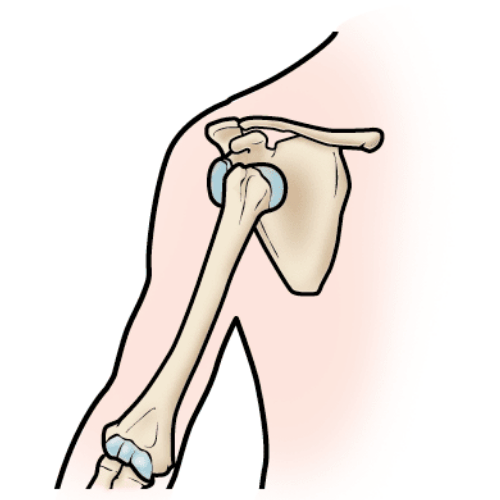

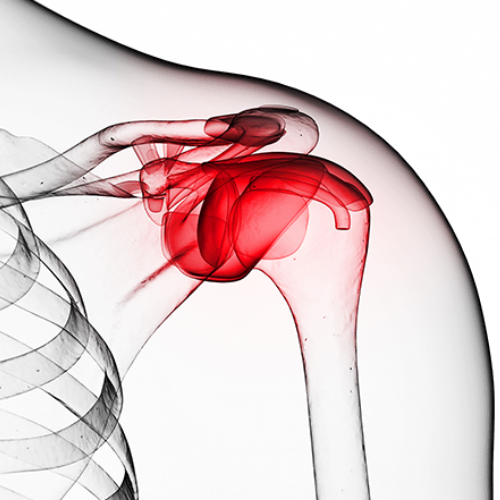

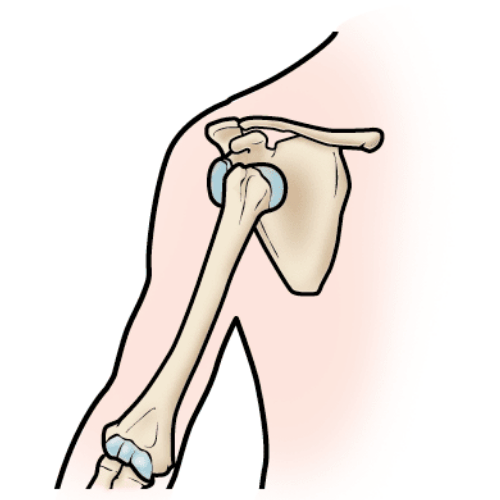

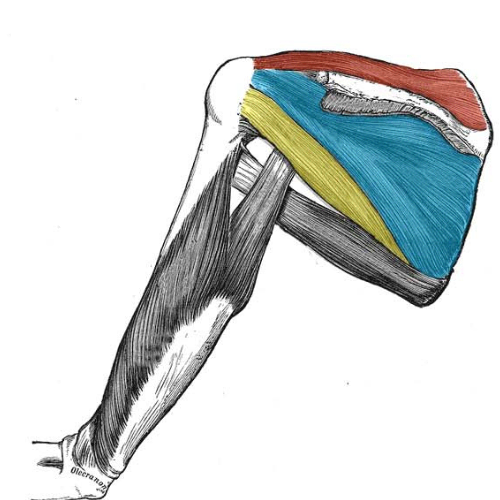

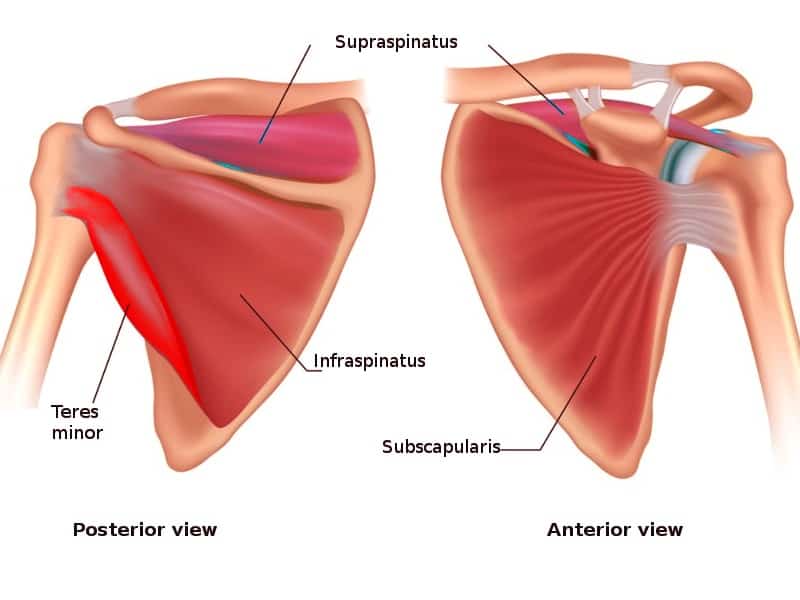

The shoulder is supported by four rotator cuff muscles that work to stabilize the “ball” of the arm in the “socket” of the shoulder blade. The tendons of these muscles – the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis – blend to form the rotator cuff. A rotator cuff tear is an injury to one or more of the rotator cuff muscles or tendons of the shoulder.

Rotator cuff tears are surprisingly common in the general population, with roughly 22% of people having either a symptomatic or asymptomatic tear.1 Of those 22%, roughly 35% of tears contributed to symptoms and 65% did not. The most common muscle affected when discussing a torn rotator cuff is the supraspinatus muscle.

Let’s discuss two scenarios for how a typical person would seek help for a sore shoulder.

In scenario one, this shoulder injury would be considered non-traumatic and is most likely due to a degenerative process such as tendinopathy, although a tear may still be present. Tendon issues are common as you age and respond well to exercise and rehabilitation.

Scenario two can be classified as a traumatic shoulder injury. The management may be the same as scenario one, however it is important to obtain imaging as this can determine the extent of the injury and possibly change management (surgery vs conservative). A proper evaluation is vital to know what steps to take after a shoulder injury.

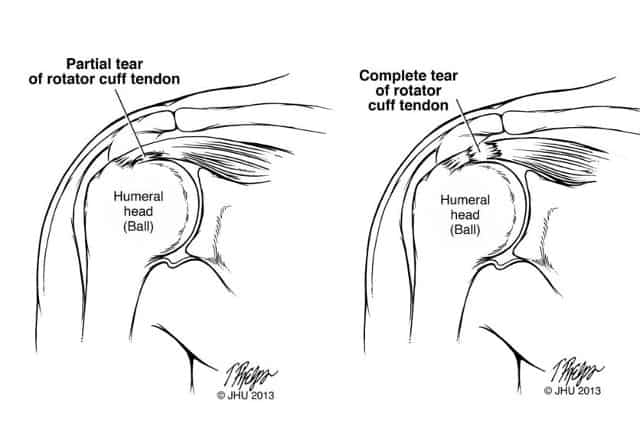

There are two types of rotator cuff tears – partial and full thickness. Partial tears are divided by location and size. Location refers to articular (i.e. damage to the underside of the tendon) and bursal tear (i.e. damage to the top of the tendon). Tears are categorized as being above or below 50% of the tendon thickness.

A full thickness tear involves multiple tendons or is greater than 5cm in size. The young man in our second scenario would be a candidate for surgery if he had a full-thickness tear from his traumatic fall.

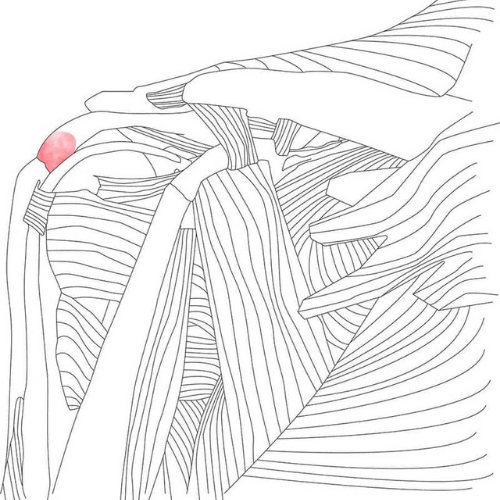

Shoulder pain can occur without having sustained an injury due to changes in the tendon. This is known as tendinopathy, but sometimes labeled as tendinitis, tendinosis or sometimes – mistakenly – bursitis. Some background reading on tendons is recommended to understand its structure and function. Briefly, when the shoulder is overloaded – which can occur after a sudden increase in activity such as moving boxes, vigorous cleaning or starting a new activity – the structure of the tendon gradually changes. During this process, the water content increases and the tendon swells up. Unfortunately, in the shoulder, there is not much room for the tendon to swell as it sits directly under the acromion bone.

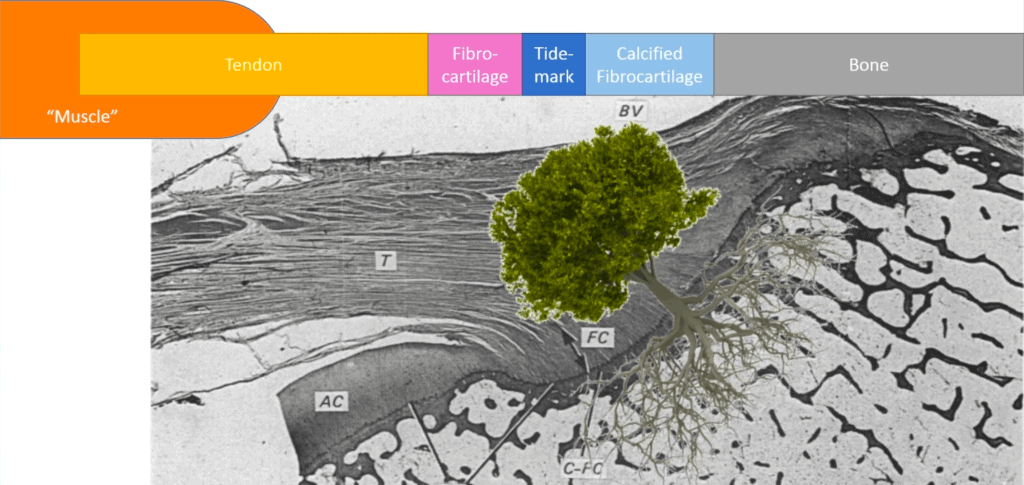

The tendon can also get compressed over the head of the humerus, especially with the arm down by the side.2 Tendons are designed to handle tension forces not compressive forces. Cartilage, such as in your knee, is designed for compressive forces. As the tendon gets compressed, the structure can change to mimic cartilage. The structural change can lead to shoulder dysfunction and pain.

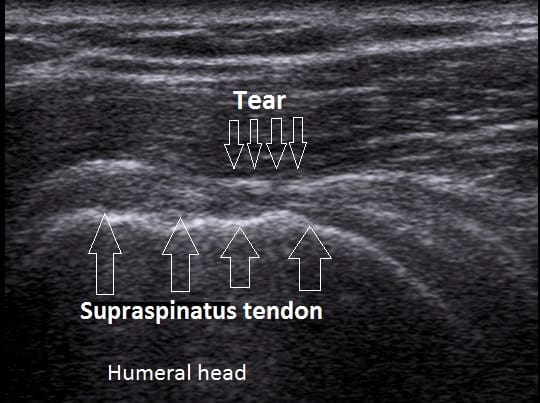

Ultrasound is the preferred method of detecting partial and full thickness tears.3 However in some cases, MRI may be warranted if an ultrasound does not detect anything, or someone does not improve despite effective conservative management.

In general, most people with non-traumatic shoulder pain do not require imaging unless conservative management does not help improve symptoms.

In most cases, especially for partial tears, a conservative approach including active rehabilitation is recommended. This can include physiotherapy, chiropractic, or massage therapy. There is still conflicting evidence about the ideal situation to perform surgery for a torn rotator cuff. Recent meta-analyses haven’t found a difference in outcomes between surgery or conservative management for treating a rotator cuff tear.4

The conflicting evidence likely stems from the fact that people with different types of rotator cuff tears are grouped in these studies – such as those with traumatic and non-traumatic cuff tears and partial versus full-thickness tears. It has been suggested that those with traumatic, full-thickness tears, especially in a younger patient, are better candidates for surgery.

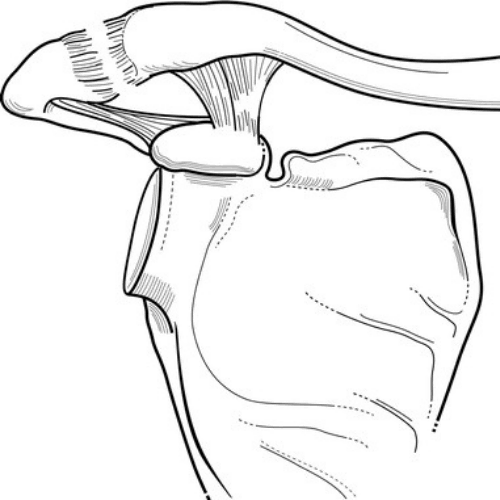

Protecting the repair site is critical because the tendon has to heal to the bone. Think of the tendon as a tree, complete with roots. The muscle and tendon are the tree trunk and the roots are how the tendon inserts into the bone.5 When a repair is done, the roots need time to integrate back into the bone to make the connection stronger. Rotator cuff repair surgery is analogous to replanting a tree. During this process, which usually lasts for 6 weeks or so, the tendon cannot withstand normal forces placed upon it. It is important to protect the shoulder during this phase.

Phase 2 Involves regaining functional mobility and strength of the shoulder. Less protection is needed during this phase so exercises can be gradually increased.

The last phase involves more challenging exercises, faster dynamic movements, and sport-specific drills.