What is Frozen Shoulder?

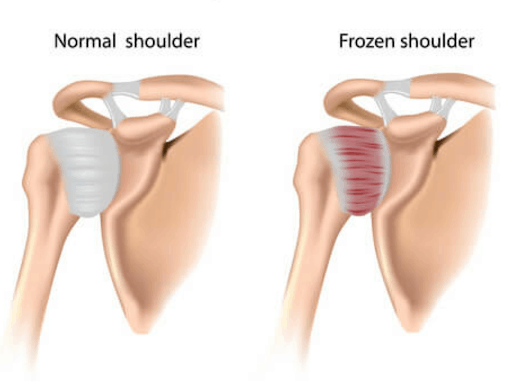

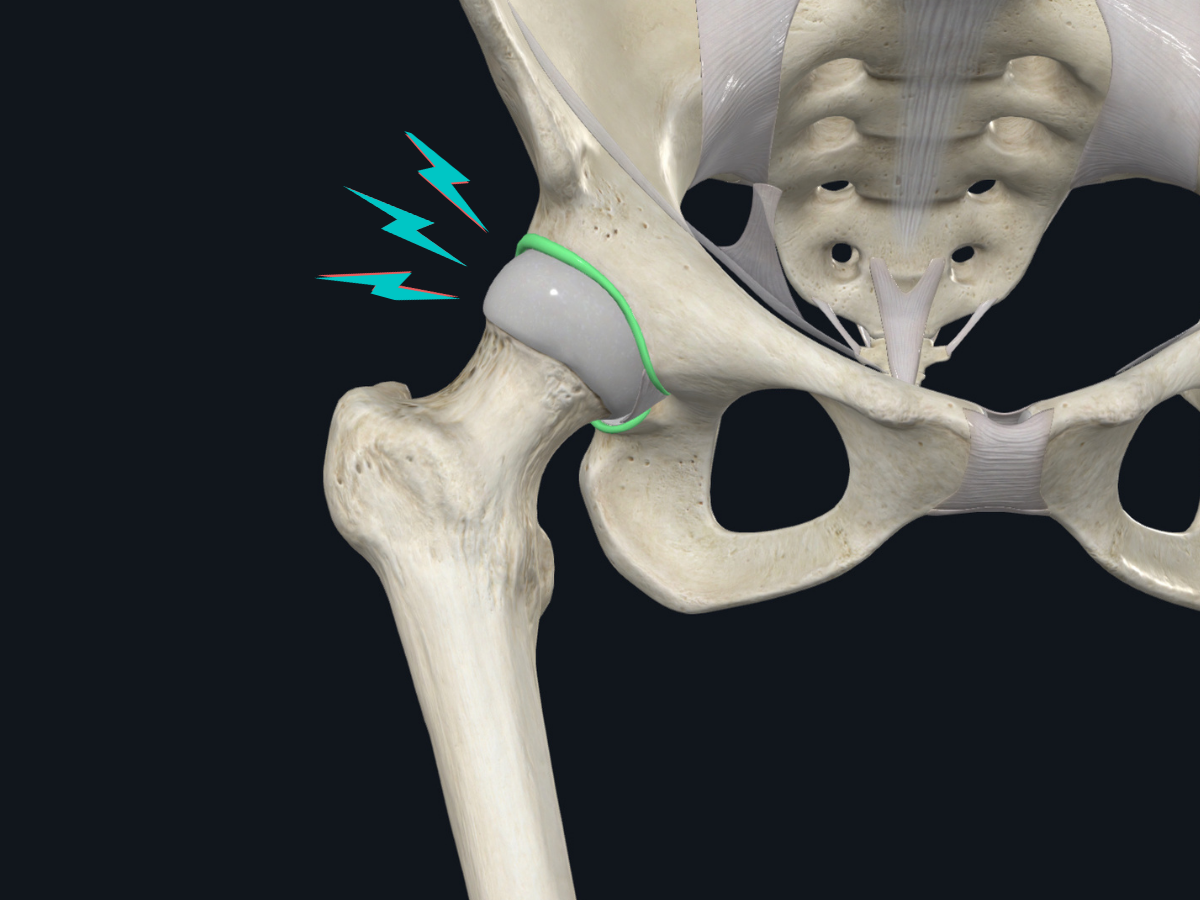

Adhesive capsulitis, sometimes referred to as frozen shoulder, is a thickening of the joint capsule (known as fibrosis) that surrounds the shoulder (also called the glenohumeral joint). It is characterized by severe shoulder pain and progressive loss of shoulder range of motion. It predominantly occurs in women more than men, between the ages of 40-65 years old1. Frozen shoulder affects between 2-5% of the general population, but that number is higher in certain populations with pre-existing health conditions.

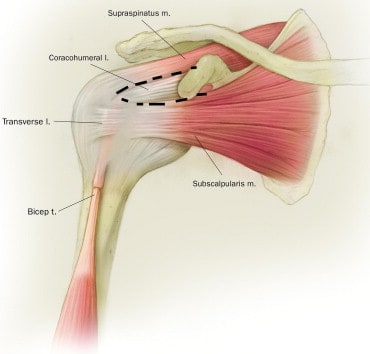

To understand how the shoulder gets limited in the way it does, let’s start by looking at the anatomy of the glenohumeral joint.

This is the front (anterior) view of the right shoulder, with the outer layer of muscles removed. The area with the dotted line surrounding it is called the rotator interval. This is the area that is primarily affected once frozen shoulder begins. Due to the connections of the ligaments on the shoulder joint, it initially restricts external rotation of the shoulder (i.e. rotating your arm outwards from the side of your body). Eventually, the rest of the shoulder capsule begins to thicken and contract, causing further mobility restrictions that become more noticeable as frozen shoulder progresses.

What Causes Frozen Shoulder?

The exact mechanisms behind the development of frozen shoulder are unknown, however there are a few theories that have been proposed1. In general, there are two categories and three subtypes of frozen shoulder:

Primary Idiopathic

In most cases, there is no identifiable reason why you may have developed frozen shoulder. In these cases, the term idiopathic is used - meaning “a disease of its own”, and not relating to any one specific cause.

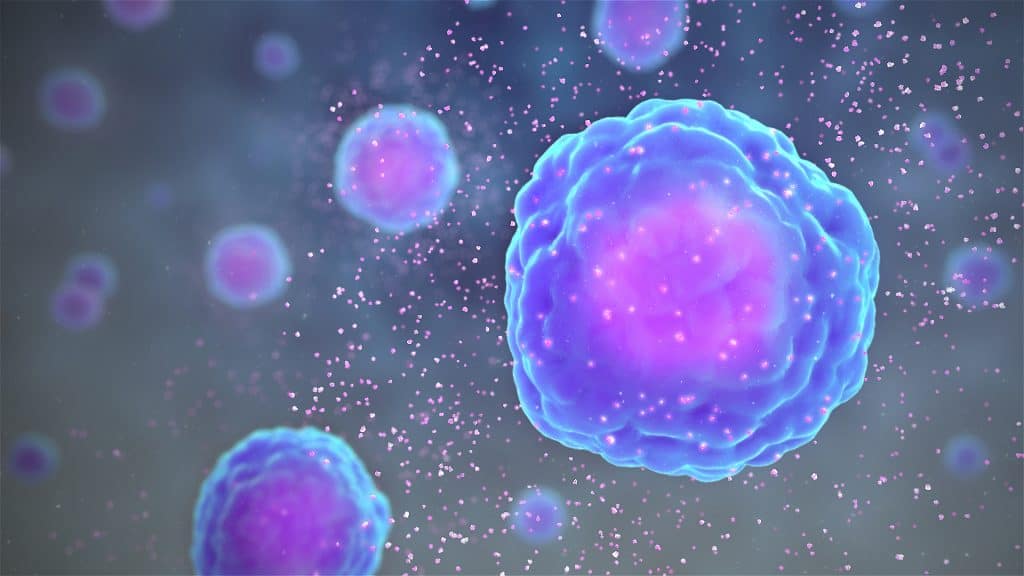

The primary mechanism that is described is an inflammatory process involving an increase in cytokines within the bloodstream. Cytokines are substances involved in the inflammatory process and help to facilitate tissue repair. It is theorized that cytokine levels remain elevated during frozen shoulder, causing an unchecked stimulation of fibrosis - a process by which excess collagen formation causes a thickening of the shoulder joint capsule.2

Secondary

The term secondary refers to the development of frozen shoulder due to a link between an existing health condition or biological process. There are three subtypes.1

Intrinsic

Intrinsic frozen shoulder primarily develops due to issues with the structures surrounding the glenohumeral joint, such as an underlying rotator cuff pathology. In these cases, you may initially be diagnosed with rotator cuff tendinitis but, over time, this can develop into frozen shoulder. Both conditions can be present at the same time, although a diagnosis of frozen shoulder will alter the course of your treatment plan.

Extrinsic

Extrinsic frozen shoulder includes factors that are not related to the shoulder, such as heart disease, previous surgery, Parkinson’s or musculoskeletal trauma such as a humeral fracture. These conditions increase the risk of developing a secondary frozen shoulder. It is crucial that a previous injury or surgery is promptly dealt with and that the shoulder is not immobilized for long periods of time as this increases the risk of developing frozen shoulder.

Systemic

This category plays a major role in the likelihood of developing frozen shoulder. People with underlying systemic conditions such as thyroid dysfunction or diabetes are at a greater risk. In fact, the occurrence of frozen shoulder in those with diabetes mellitus is as high as 20%, which is four times higher than in those without diabetes3. Unfortunately, systemic comorbidities also contribute to a lengthened recovery period.

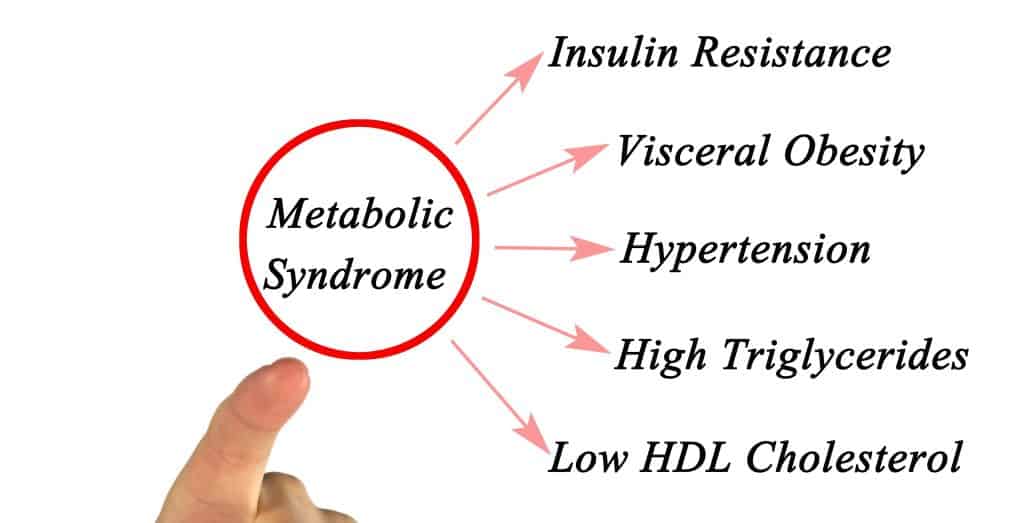

Since two main risk factors for frozen shoulder are cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes, a few studies have looked into possible links to metabolic syndrome4. Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of five risk factors - a large waistline, low levels of high density lipoprotein (good cholesterol), and high blood pressure, blood sugar, and triglycerides levels - that occur together and increase your risk of developing heart disease, CVD, and stroke. What makes this link interesting is the presence of chronic low-grade inflammation in the body with metabolic syndrome. As mentioned earlier, the inflammatory process involves increased cytokine levels in the bloodstream. Since cytokine upregulation is involved in primary frozen shoulder, it is possible that metabolic syndrome could be a driver of primary frozen shoulder in some people. In these cases, diet may play an important role in treating frozen shoulder. Choosing foods that can lower inflammation in your body and control glycemic response is a cornerstone of diabetes management but may also influence frozen shoulder.

What are the stages of frozen shoulder?

Frozen shoulder has historically been separated into three phases - freezing, frozen, and thawing. While this terminology is still used clinically, the research has moved to a broader, two category classification5: pain > stiffness and stiffness > pain.

Pain > stiffness stage

The initial stages predominantly involve severe pain with less noticeable limitations on shoulder joint movement. Severe pain can be constant at rest, at night and during sleep, causing sleep disturbances.

Stiffness > pain stage

As the condition evolves, pain begins to subside and stiffness increases. This is generally a more manageable stage for most people, as they can sleep without interruption. However, the functional impact of a severely limited shoulder joint can be profound.

How is frozen shoulder diagnosed?

The diagnosis of frozen shoulder begins with a thorough subjective history and physical examination to exclude other possible causes of shoulder pain and stiffness. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard test for diagnosing frozen shoulder. Because of this, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning that we must rule out other causes before labeling it as frozen shoulder. Clinically, there are a couple of key tests that are done to aid in this diagnosis:

- Active and passive joint mobility equally limited (usually a loss of >50% of normal shoulder motion)

- Normal x-ray

It is important to correctly diagnose frozen shoulder because the treatment and prognosis of this condition differs from other shoulder conditions.

How long does it take to recover from a frozen shoulder?

The natural history of frozen shoulder is 2-3 years from symptom onset to recovery6. This number is large, but it is important to remember that this is the natural history without any intervention. In addition, many people who wait for spontaneous recovery still experience symptoms and functional deficits after three years. Sometimes patients are given the advice to follow a ‘wait and see’ approach (known as supervised neglect), however the research evidence shows that there are effective treatments available that can significantly reduce long term disability. Clinically, we’ve seen true frozen shoulder symptoms improve over 6-12 months, but this timeline is variable and depends on individual factors.

What is the treatment for frozen shoulder?

There are a few main treatment options for frozen shoulder. At Kinetic Labs, we use a combination of treatment approaches.

Manual therapy (including joint mobilization, stretching, and massage)

Recent studies have found that a course of treatment involving manual therapy techniques to mobilize the shoulder joint is effective. Many of the studies examining the effectiveness of manual therapy were done in a non-diabetic population during the stiffness > pain phase. Overall manual therapy, provided in some form at least 3 times per week for 10-30 minutes, resulted in significant improvement in function, pain scores and range of motion5. These beneficial results are less clear in those with diabetes.7

Exercise (strengthening and stretching)

Exercise is an effective intervention for frozen shoulder. A recent systematic review found that therapeutic exercise was particularly effective in the sub-acute stage when pain decreases and joint mobility gradually becomes stiffer6. Regardless of what stage you are in, a home exercise program is essential to regain the normal functioning of your shoulder. This can include strengthening, stretching, and upper limb endurance exercises.

One study found that 15 minutes on an upper limb cycle ergometer two to three times per week, combined with shoulder joint mobilizations, significantly improved the range of motion and overall function8.

We use an Airdyne bike in our clinic to help improve endurance and mimic the effects of the upper body ergometer. Clinically, we find that exercises combining stretching and strengthening, such as eccentric exercises, are an effective way of increasing the range of motion while improving muscle function.

Corticosteroid injection

Cortisone injections are usually the first intervention that is considered during the pain > stiffness phase. A randomized control trial compared a group receiving physiotherapy versus a group receiving both physiotherapy and a corticosteroid injection and found that the combination therapy group showed a higher reduction in pain scores9. In a separate study, researchers compared corticosteroid injection and physiotherapy versus corticosteroid injection on its own and found that, once again, combination therapy led to greater improvement at 3 months in early onset frozen shoulder10.

Hydrodilatation

Hydrodilatation - also known as distension arthrography - is a joint injection of sterile saline solution that is commonly used to stretch out the joint capsule and its adhesions. This is generally used for patients with persistent symptoms (> 6 months), poor response to conservative management, and significant functional limitations due to restricted shoulder range of motion. A recent study followed over 2400 people who received hydrodilatation over a ten year period for adhesive capsulitis, and found that it provided significant shoulder mobility increases without the need for a follow-up injection11. Interestingly, repeat injections were required more often in those with diabetes.

Other interesting theories in frozen shoulder

The role of muscle guarding

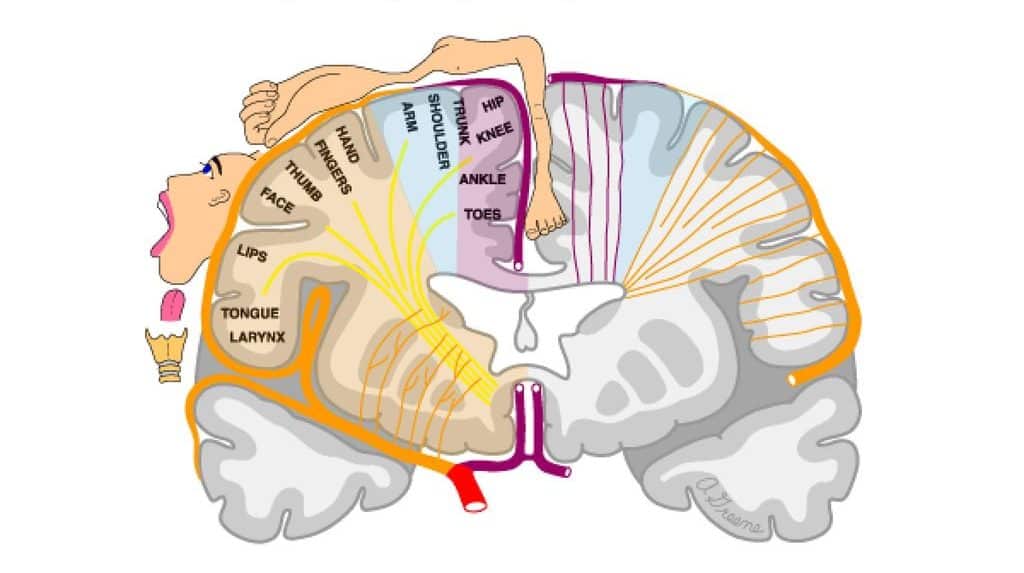

If adhesive capsulitis involves thickening of the shoulder joint capsule, then any improvements in range of motion are expected to be slow due to the inability of fibrous tissue to change quickly. However, some recent studies have called into question the role that capsular thickening plays in the clinical presentation of frozen shoulder. In one study, five patients with frozen shoulders who were put under anesthesia had a passive shoulder joint range of motion increase of between 55-110 degrees compared with pre-anesthesia motion12. This is over double the range of motion! How is that possible? One explanation involves muscle guarding. Our brain subconsciously protects an area by reducing the degrees of freedom of that joint when we experience pain or an injury. It is our body’s way of splinting the area to prevent further damage. However, our brain’s estimation of damage is not always accurate and can result in our body overprotecting the area. It is possible that muscle guarding plays a larger role than joint contracture does in limiting shoulder range of motion in some people diagnosed with frozen shoulders.

One way to combat this is by using your affected arm as much as possible throughout the day. Doing so helps to sharpen the cortical maps within your brain. Each body part is represented by a specific region in your brain. When experiencing pain or with disuse of that body part, the cortical maps become fuzzy. The change in limb representation within the brain can be a driver of pain and disability and can feed into protective responses such as muscle guarding.

Is my shoulder truly frozen?

The observation of muscle guarding in people diagnosed as having frozen shoulder raises more questions. Are those diagnosed with frozen shoulder but no contracture really frozen? How can you tell, clinically, if the joint capsule is actually contracted or if muscle guarding is to blame? Is muscle guarding without a contracture a subset of frozen shoulder or something entirely different?

Unfortunately, we don't know how to tell them apart without doing further investigations (histopathology, etc). However, these investigations are not typically needed for successful treatment. If we were to look at the joint capsule tissue of a frozen shoulder patient under a microscope, there would be an increase in cells such as fibroblasts (produces connective tissue) and myofibroblasts (similar to fibroblasts, but have the ability to contract like a muscle).13 An increase in myofibroblasts in the joint tissue could potentially explain why the shoulder becomes stiff, as they contract and shrink the capsule.

Myofibroblasts are present in the early stages of frozen shoulder as part of the immune response. It's possible that a corticosteroid injection is helpful in the early stages due to its strong anti-inflammatory effect that can potentially deactivate myofibroblasts, slowing or preventing the contracture in the first place.

Can you stretch a frozen shoulder?

Assuming someone has true frozen shoulder, how likely is it that you can stretch the joint capsule? One study has shown that it takes 683kg of force to stretch the shoulder capsule.14 If we're lucky, our manual therapy provides 20-40kg of force, and certain not much more than our body weight. So it's unlikely that our stretching has any direct effect on the elasticity of the capsule. However, that does not make it a useless treatment. As mentioned previously, manual therapy can have dramatic effects on pain and muscle guarding and can hasten the recovery of shoulder function.

This study also has implications for some other treatment options, mainly hydrodistension. It's unlikely that a 30mL injection of saline solution can create enough force to stretch the capsule. However, once again people do experience dramatic differences in range of motion after these procedures. The question is whether that is due to the capsule being stretched, or from another mechanism entirely such as reduced muscle guarding.

Conclusion

The main takeaway from this article is to understand that although the recovery process of frozen shoulder is long, there are effective treatment options available. Regardless of which path you take, it is always a good idea to start with a low risk option such as a comprehensive exercise program.

References

- https://bit.ly/2P2cMhl

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22999851

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20701586

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26880627

- https://bit.ly/3g76QQj

- https://bit.ly/307hEIq

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5009124/

- https://bit.ly/307HnjO

- http://jpoa.org.pk/index.php/upload/article/view/329

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6153137/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5706054/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29986193

- https://bit.ly/39sfpVg

- https://bit.ly/3qkykHq

.png)