Calf strain, also known as “tennis leg” or “calf tear”, is a common injury in running sports such as tennis, American football, Australian football, basketball, and soccer. The injury occurs most frequently in athletes between the ages of 22 and 28 and affects men more often than women, with 19% to 31% of cases being a recurrent strain. The recovery period for a calf strain can range from a few days to multiple months of missed practice or playing time.

The risk of injury varies depending on the sport and type of activity, with gastrocnemius strains being more associated with high-intensity running and acceleration activities and soleus strain being more likely to occur during steady-state running activities. The differences in each muscles’ biomechanical structure influence this injury risk. The gastrocnemius is dense in fast-twitch muscle fibers adapted for rapid contractions such as sprinting, while the soleus is dense in slow-twitch muscle fibers adapted for postural control and endurance running.

The calf primarily consists of two large muscle groups – the gastrocnemius and the soleus. Most people think of the gastrocnemius when describing the calf because it is the outermost muscle in the lower leg. It cross the ankle and knee and is involved in bending your knee as well as pointing your foot. The soleus muscle contributes to the push-off when walking or running as it only cross the ankle joint and not the knee. The two muscle groups combine into the Achilles tendon that attaches to the back of the heel. While there are deeper muscle compartments in the lower leg, this article will focus on the gastrocsoleus complex.

Yes, a muscle strain can occur in either the gastrocnemius or soleus. A gastrocnemius strain is an injury that usually occurs when the knee is extended and there is a sudden “push-off” movement of the foot, especially when the muscle is maximally stretched. This can cause the muscle to tear, often in the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle, which is more prone to injury. A soleus strain is an overuse injury that can occur from repetitive and passive movement of the foot with a bent knee. This often occurs in runners when they are running uphill. Soleus injuries occur from a gradual and cumulative effect but can also happen suddenly in tired athletes.

Here are the symptoms most often associated with a gastrocnemius strain:

Here are the symptoms most often associated with a soleus strain:

The following are the strongest risk factors for a calf strain:

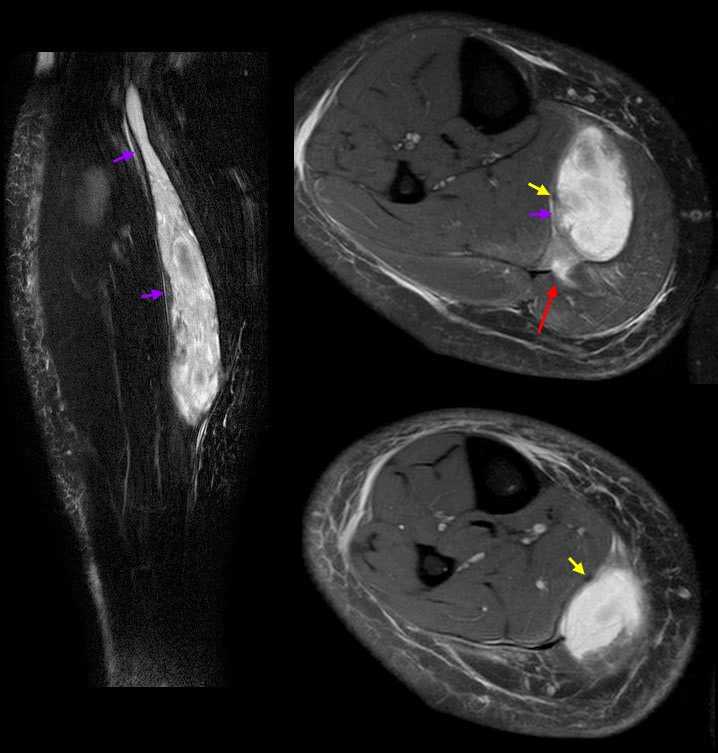

Although the diagnosis of a calf strain can often be made through a clinical examination, imaging can be useful to confirm the location and severity of the injury. However, in most cases, imaging won’t be necessary unless the recovery is slow or stalled.

Musculoskeletal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are good choices for imaging calf strains. MRI can provide a more detailed view of the injury, including surrounding tissue damage, and can help to evaluate the healing process. Ultrasound is cheaper, more accessible, and faster, and can provide information about the presence of blood clots or other complications. However, there are no specific guidelines for using ultrasound to determine when it is safe to return to sports activities. This is because imaging doesn’t determine the level of function you have.

A calf strain can be mild, moderate, or severe, depending on how much the muscle is damaged. Mild strains (with <10% of muscle fibers injured) cause only a little pain or soreness and should heal in one to four weeks. Moderate strains (10-50% of muscle tissue injured) cause more pain and swelling and can take two to five weeks to heal. Severe strains (>50% of muscle fibers disrupted) cause a lot of pain and disability, and can take five to ten weeks to heal with conservative treatment, or up to 24 weeks with surgery. The timelines above give a general guideline of the body’s natural healing process. Recovery times can vary dramatically depending on the demands of the activities that you wish to return to. A muscle may be fully “healed” but still not able to withstand the high forces of running or jumping without further rehabilitation.

The first question we often get from a client is “when can I run again?”. This is dependent on the location and severity of the injury, as well as the demands of the activity, but there are some general guidelines to follow.

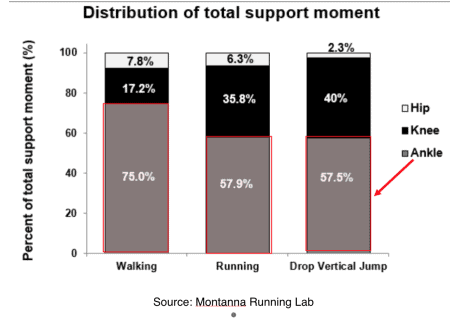

Did you know that more than 50% of the force that propels a runner forward comes from the muscles in the calf? Many people believe that the hip muscles are most important for running, but research shows that only 5-10% of the force comes from those muscles. The majority of the work is done by the muscles below the knee.

A comprehensive rehab program is so important because of the forces that the calf muscles are exposed to when running. The soleus muscle alone can generate a peak muscle force of 6.5-8 times your body weight, while the gastrocnemius muscle can generate 3.5-4 times your body weight. The soleus muscle is particularly important, as it generates high peak forces at all running speeds.

A gradual, return to running protocol is an important rehab milestone that allows you to safely return to running after a calf tear.

Non-operative management is effective for most calf strains and can be separated into 3 phases: acute, subacute and return to sport.

Acute Phase

The acute phase occurs immediately following the injury and lasts for the first 24 to 72 hours. The primary goal during this phase is to protect the injured tissue by reducing activity, managing pain, and preventing hemorrhage or other complications. Treatment for the acute phase includes:

Subacute Phase

The subacute phase begins after the acute phase and typically lasts for about 2 weeks. During this phase, the body repairs the soft-tissue damage and forms scar tissue. The goal of treatment during this phase is to restore mobility, prevent muscle atrophy or contracture, and guide tissue regeneration to optimize functional improvement.

It is important to focus on building strength and tissue resilience in the calf muscles during this phase. While soft tissue massage and stretching are popular self-care strategies, they are not enough to fully rehabilitate a calf strain. It is essential to load the calf with appropriate exercises as soon as possible to achieve a timely recovery outcome. It is normal to be hesitant to load the calf for fear of delaying your recovery, but this can result in greater muscle deconditioning. Reluctance to return to running and a too cautious approach to rehabilitation can also prolong recovery. Calf rehabilitation exercises typically start with home-based exercises, followed by gym-based exercises if possible. While home-based exercises are good for restoring early load tolerance, maximal strength gains may not be achieved without engaging in rehabilitation exercises with suitable resistance in a commercial gym facility.

Return to Sport Phase

A comprehensive program must be developed to determine when you can start running again while rehabilitating a calf strain. It is important to find a middle ground between being too conservative and too reckless, and to consider your goals and preferences as well as specific demands of your sport. The first step is to be comfortable running. Before commencing running, minimum criteria should be met, such as being able to walk without pain and single-leg hop 10 times without pain. Flare-ups of symptoms during a return to run program are common and don’t necessarily mean reinjury. A conservative walk/run program is a good starting option, with gradually increasing running time and decreasing walk time each week. It’s important to continuing progressing your rehab to achieve continuous running for up to 60 minutes before adding speed work.

Once speed work is added, other sporting demands such as change of direction, agility, and plyometric drills can be incorporated. Gradual return to training, practice and then competition follows.

Most calf strain injuries don’t require surgery, but in more severe cases, it might be necessary if the muscle is completely torn or if there are complications like scar tissue, swelling, or bone growth in the muscle. If you can’t stand on your toes on the leg with a calf strain, it could be a sign that surgery is needed.

During surgery, the surgeon will repair the muscle and remove any scar tissue. After surgery, you’ll need to wear a bandage to keep the muscle immobilized and use crutches to walk. You won’t be able to put any weight on your leg for the first 4 to 6 weeks. Rehab can be started soon after, even if it is to prevent muscle and strength loss in the supporting musculature. It can take 6+ months to fully recover from the surgery.

A successful calf muscle rehabilitation program after a strain involves a progressive strength program that focuses on increasing and optimizing the load capacity of the calf muscles. This program typically takes several weeks and involves consistent completion of both home and gym-based exercises. If you fail to restore the load capacity of your calf muscles, you may continue to experience symptoms or be at risk of recurring strains or injuries.